Where was tattoo-less Elie Wiesel in 1944 if not at Auschwitz?

Saturday, March 5th, 2016

Followup of “Elie admits he doesn’t have the tattoo A7713”

By Carolyn Yeager

copyright 2016 Carolyn Yeager

![Elie Wiesel's left arm in bright sunlight in a still from his own video "Elie Wiesel Goes Home" - no retouching. [courtesy Eric Hunt]](https://www.eliewieseltattoo.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/EW_arm-no-tattoo1-e1450887466391.jpg)

Elie Wiesel’s left arm in bright sunlight in a still grabbed from his own movie “Elie Wiesel Goes Home” – no retouching possible. [courtesy Eric Hunt]

Turns out? How long do we wait for something to “turn out?”

Wiesel will be 88-years-old on September 30th of this year. Very few human bodies are able to carry on after their 90th year, so, without a consensus opinion from the revisionist community, we are looking at the prospect of an eternal “We’ll never know” pasted over the Elie Wiesel tattoo question. Naturally, this is what Wiesel supporters want, but should revisionists be content with never going beyond that, continuing to fear there will come a time he will dramatically pull up his sleeve for the cameras?

He’s already done so and we have the result in the image at right.

And what don’t people understand about logic? One doesn’t need a University course in logic to use common sense. Two plus two adds up to four – we don’t need a calculator to prove it, our fingers can tell us. What should we think of those who would say “But what if it doesn’t? What if our fingers turn out to be wrong?”

It’s the same logic we use when someone tells us he has a number tattooed on his arm that proves he was at Auschwitz in 1944 – we expect it to be shown to us. There is no reason we should have to take it on trust. Imagine yourself in a real life situation like that and you’ll get it. Those who are willing to accept a deal such as we have in the case of Elie Wiesel are either cowards, frightened serfs, or collaborators in the lie. But people are also ignorant of the facts – even though mostly through choice, and maybe also poor memory.

For this reason, I want to specifically address these persons to try to give them a little backbone … er, I mean background. You need to be clear about how Elie Wiesel got into this tattoo quandary to begin with.

To those whose reasoning goes, Why would Wiesel say he has a tattoo when he doesn’t have one? He wouldn’t be so foolish, therefore I have to assume he might have one. He also doesn’t need to have a tattoo to have been at Auschwitz, – they forget about the Yiddish book, Un di Velt hot gesvign (And the world remained silent), from which Night was taken. In that book, and carried over to Night, Eliezer and his father were tattooed on their left forearms with A7713 and A7712. It follows that if Night is Elie Wiesel’s own story, he has to have a tattoo.

On page 51, the author wrote:

The three “veterans,” with needles in their hands, engraved a number on our left arms. I became A-7713.

Now I hope you understand (and please don’t forget it again) why he has to have that particular tattoo, and why he has always said he does have it. He has no choice. The fact that it has never been shown to the public speaks volumes (never underestimate his belief in his ability to fool the public), as well as the fact that we’ve seen his uncovered left arm in photographs and there is no such number there. What more proof do you want? The final nail in the coffin is that Wiesel and the people around him remain silent about it – they will not allow the question to be asked. That is the “admitting” part.

So it’s settled – Wiesel has no tattoo, and he admits as much. He’s kept up the lying charade so long because he could! No one challenged him. Once again, I will give credit to Jew Michael Grüner for breaking this open, even though he makes up plenty of ridiculous concentration camp stories himself. But Grüner got the documents and made them public, along with explanatory letters from Auschwitz and Buchenwald.

If Wiesel is not a concentration camp survivor, we need to look into other possibilities for his whereabouts in 1944. We will not be able to prove anything – this period of time could not be more confused. Displaced persons and self-identified camp survivors were flocking into Western Europe in search of opportunities; they were creating new identities and applying to go to Israel and to America. In all of this, it’s impossible to find any kind of a trail. But some pathways are more plausible than others for the Wiesel family.

Wiesel’s family is not found in records at Auschwitz

Speaking of documents, do you know there is no record of any member of Wiesel’s immediate family at Auschwitz? That’s a fact. In addition, the only record, as far as I know, of Elie’s two older sisters being at the Dachau sub-camp Kaufering comes from a book put out by the “Central Committee of Jews in Bavaria” in 1946. They published a list of 61,387 Jews in a book named Sharit Ha-Platah (translates as “Counted Remnant”), among which are listed Hilda and Bea Wiesel. The names were collected by Chaplain (Rabbi) Abraham Klausner, who is said to have visited many of the camps in southern Germany where survivors gathered in late 1945 and 1946. You better believe the Rabbi wanted to get as many names as possible, and that there is nothing official about this list.

We first meet up with Hilda and Bea as refugees in Germany, just as we first meet up with Elie at a Jewish orphanage in France. Hilda Wiesel married an Algerian Jew and moved with him to Paris. She has since spoken about her family’s deportation in a Shoah Foundation videotaped interview, but without details of what happened after they arrived at Auschwitz. Her sister Batya (Bea) emigrated to Canada and never spoke publicly about it at all.

Hilda’s Shoah Foundation testimony which she gave in 1995 (coincidentally the same year Elie’s official autobiography All Rivers Run to the Sea came out) differs from her brother’s story in Night in numerous details. Relevant here, she said:

We were deported on 15 May [1944]. We heard around 1943, because we had family in Belgium, we heard that they had deported a cousin, but we didn’t know where to …

I can only tell you one thing, that the third transport – we had to stand 5 by 5, five abreast – there were Hungarian gendarmes, hardly any Germans, mostly Hungarian gendarmes.

We were myself and my sister, the one who was in Canada and is now deceased; my mother; my grandmother, that is my father’s mother; and, oh … my little 10-year old sister. And we arrive in Auschwitz, the men were apart, my father with my brother.

According to the original Night and the Yiddish And the world remained silent, the family’s deportation date was June 3, 1944. In Marion Wiesel’s re-translation, it was changed to May 20. So which is correct? Most likely none.

Hilda also tells us the women and men traveled in separate cars.

My mother knew there was no hope, because she told me and my sister, always stay together, always stay together. And she said, go tell your dad to always stay together with Elie. And I ran over to him and said, Papa, stay with Elie, stay with him – like that.

Q: This was on the train, that you are describing?

A: No, it was after getting off the train.

If they were in the same train car, Mother could have told her husband herself. But Night and its Yiddish precursor describe the boys and girls having sex together in the darkness of the train, freed from following the usual rules, and Wiesel says he was traveling with his mother and sister — everyone was together. Let me make clear that I don’t have any more faith in 70-year old Hilda Wiesel Kudler’s testimony than I do Elie Wiesel’s “stream-of-consciousness” autobiography, which, as I said, coincidentally appeared at the same time in 1995. And I am not convinced by this that the family really went to Auschwitz since not one of them was registered there, nor do their names come up on any hygiene or other reports even though they were supposedly put in quarantine. We do find Lazar and Abraham Wiesel, and Myklos Grüner, his father and brother listed on a hygiene report.

I’ll also add that Mother, Grandmother and youngest sister [10 years-old according to Hilda Wiesel, but 7 years-old according to Elie in Night, where Grandmother is not included] are understood to have been sent directly to the “gas chamber” and gone up in smoke through the chimney shortly thereafter. Since homicidal gas chambers didn’t exist, all the women would have been sent to the showers, gone through the disinfection process, given new clothing and assigned to a women’s barrack, the same as Wiesel writes about Eliezer and Father. However, a grandmother and mother with a child would have been assigned to non-working barracks; the two 20-somethings to barracks for female workers.

A very odd fact is that both in Night and in the Yiddish book, Eliezer and Father never mention their wife, daughters, mothers and sisters again. They don’t look for them, talk or ask about them, as other people did. They apparently accept being told that their loved ones “went up the chimney” and immediately become concerned only for themselves. I don’t believe this; it’s not human nature, it’s make-believe.

So if not there, where else could the Wiesel family have been in 1944?

Following a trail of possibilities

Well, we do have Shlomo and Mendel Wiesel’s first cousin Yaakov Fishkowitz filling out a Yad Vashem Page of Testimony for each of them, reporting they both died in 1943 in a “labor camp.” If Yaakov didn’t believe this were true, why would he have done this in 1957 at the same time he filled out other pages for relatives he marked as being sent to Auschwitz in 1944? He also said Shlomo was born in 1903 and Mendel in 1905.

Add to this the very weak story Elie Wiesel gives for why his family didn’t do something to protect themselves from the “Nazi menace.” On page 8 of Night, Wiesel wrote:

In those days it was still possible to buy emigration certificates to Palestine. I had asked my father to sell everything, to liquidate everything, and to leave. ‘I am too old, my son,’ he answered. ‘Too old to start a new life. Too old to start from scratch in some distant land …’

Too old at the age of 41? Fishkowitz puts his birth in 1903. Other than that, there is no official birth date for Elie Wiesel’s father. In a close family, children always know their parents’ age and birthday. Hilda said her mother was born in 1900. So Shlomo Wiesel’s age is being covered up by son Elie, who left blank the DoB space on the Page of Testimony he filled out for his father. We can say that the oldest Shlomo could have been was 48, but more likely younger. Wiesel has always made his father out to be a tired old man, especially in Night. I have distrusted this characterization and believe it was a literary device to make the story more poignant, just like turning 10 year-old Tsipora into a 7 year-old.

The following interesting passage is on page 27 of the Yiddish Un di Velt hot gesvign, but is not included in the shorter French or English Night:

We had opportunities and possibilities to hide with regular goyim and with prominent personalities. Many non-Jews from the surrounding villages had begged us, that we would come to them. There were bunkers available for us in villages or in the mountains. But we had cast aside all proposals. Why? Quite simple: the calendar showed April 1944 and we, the Jews of Sighet, still knew nothing about Treblinka, Buchenwald and Auschwitz.

Two things here. It again says it was April, not May, when the Sighet Jews first learned they would be deported. It confirms the passage on page 83 of the Yiddish book: “It was a beautiful April day,” said on one of their first days in Auschwitz-Birkenau.

The other thing – it is not true the Jews of Sighet knew nothing, yet that is what Wiesel writes in his autobiography All Rivers, while at the same time he also writes of Polish Jews passing through their neighborhoods telling stories of terrible atrocities by German occupiers. He says that non-Jews offered the Wiesel family places to stay. Wiesel writes that their Christian maid Maria begged them to come to her village and she would keep them safe. How many Jews may have taken advantage of such offers? But we’re told that Shlomo Wiesel refused to accept this kindness of Christians, and Elie’s only explanation is that they still didn’t believe the stories they were hearing. Then he blames the world for not warning them! This can be found in All Rivers Run to the Sea, on page 63 and 68-69.

Isn’t is possible the reason we find mention of these offers of help in all three Wiesel books is because it was such an important part of his experience that he felt compelled to include it? His family hid out and were protected from arrest. Or … maybe only he was sent away for safety, and his mother and sisters had different experiences. His father too, unless he did indeed die in 1943.

After the war, when only Elie and his two older sisters reunited, it was convenient to say the others were “murdered” in Auschwitz. That was the preferred story at the time. After all, with an advertised death toll of four million until 1990, there was plenty of room to say hundreds of your relatives were exterminated there.

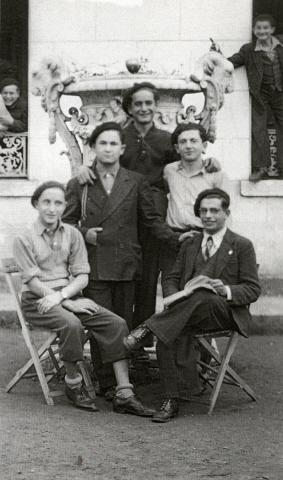

In France

Wiesel could have been sent to the home for Jewish orphans in France after the war from wherever he had been staying. In the few photographs we have, he looks cheerful and well-adjusted. He has friends, and seems to be a leader of younger boys. His hair is very long in the front, too long to have grown out from a concentration camp shaved head just a few months before.

From his very first year in France he was extremely interested in Zionism, the struggle in Palestine, and was a supporter of the Irgun, the Jewish terrorist organization in Palestine. Where did he learn all this, since he says that while in the camps he had no interest in anything. This is another reason to suspect he sat out the “Hungarian Holocaust” and was staying in a safe political environment somewhere.

I have written so many details in the various articles on this site that suggest or show outright that Wiesel has lied about many, many things – that he is faking it when it comes to so many aspects of his story. It’s not like he’s a paragon of truthfulness and I am therefore going out on a limb, or defaming him, by questioning the basics of his story. What really gives me a justification to do so comes back to – yes, that’s correct, his lack of a tattoo!

I think it shows that Wiesel and his friends know how damaging this tattoo business is by the fact they won’t speak about it – they completely refuse to deal with it. The Jewish Shoah believers in France at Enquete & Debat tried but could not get Wiesel to answer any questions about the tattoo by writing to him at his Foundation office in Romania. After a period of time they phoned there and Wiesel’s assistant hung up on them as soon as she realized what they were calling about. If holocaust-believing Jews are treated that way, it tells us just how unwelcome the topic is.

As I’ve said before, the only way to bring attention to Wiesel’s serious tattoo problem is to make a lot of noise about it – to get public attention on it. This is not happening and will not happen as long as the general response is: Forget the tattoo because it might turn out that he has one.

The cowardice in such a position leaves me flabbergasted. It’s half ignorance, as I said above, that is true, but the other half is lack of nerve. I am doing my best to dispel the ignorance. Those promoting the Wiesel legend lie, lie, lie, lie, lie and it doesn’t bother them in the least, while the truth forces are afraid of being wrong when the odds for being wrong on this are 5% or less – to me, it’s 0%. To continue to be content with just asking the question “Is it possible that Elie Wiesel doesn’t have the tattoo he said he does?” and fail to go beyond that to a declarative statement on the matter is not an acceptable outcome considering all we know.

It’s time to put all doubts aside and claim the obvious.

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: Auschwitz, Elie Wiesel, Hilda Wiesel, Night, Shlomo Wiesel, Un di Velt Hot Gesvign, Where's the Tattoo?,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.