Naftali Fürst claims to be in the Famous Buchenwald Photo as a 12-year-old boy

Tuesday, January 8th, 2013

By Carolyn Yeager

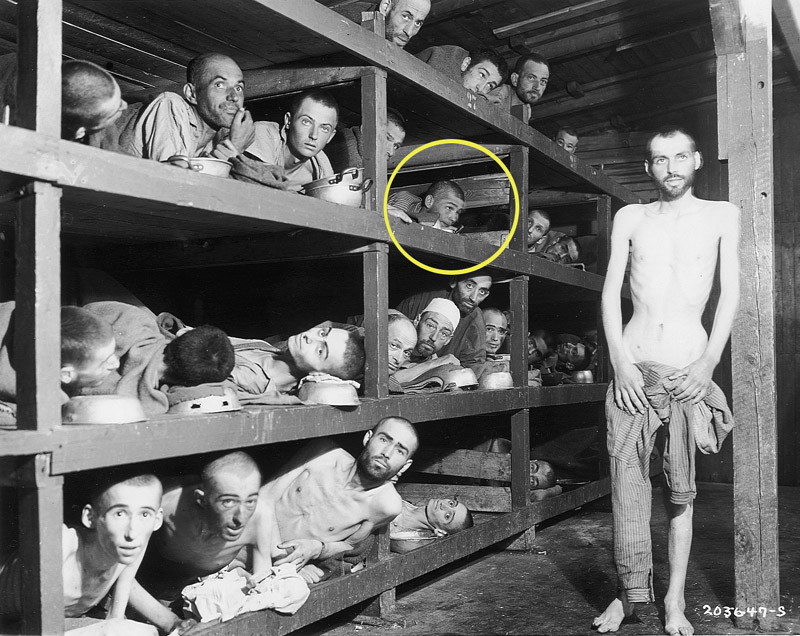

The man who now calls himself Naftali Prince (Fürst translates to Prince in English), and who was also known in childhood as Duro Forst, is the person circled in both photos below, taken at around the same time shortly after the Buchenwald “liberation” on April 11, 1945.

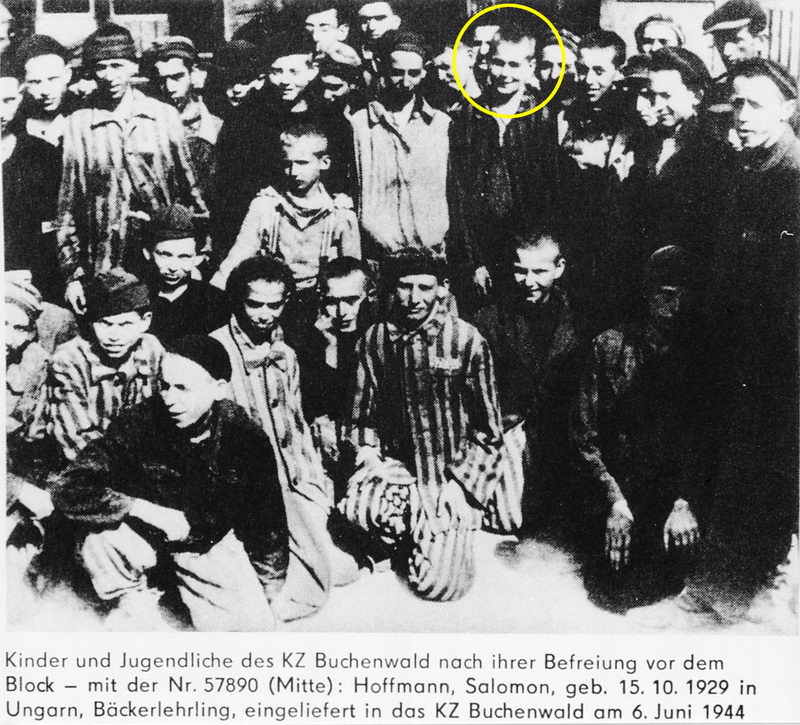

Above: “Buchenwald children on the release day. Naftali Fürst is marked in a yellow circle.” (As per Naftali’s website, http://furststory.com/English/Holocaust_Kinder.html)

Above: “Buchenwald children on the release day. Naftali Fürst is marked in a yellow circle.” (As per Naftali’s website, http://furststory.com/English/Holocaust_Kinder.html)

Below: “Buchenwald. Naftali Furst is marked with a yellow circle.” Can this be a 12-year-old boy? The man two rows directly below him is identified as being 25-yrs old.

Below left: “Our parents and us after the war” (As per http://furststory.com/English/YaldutMomDad.html) Naftali is to the left of his father, although he strongly resembles his mother, while his older brother takes after their father.

Why is it that he looks younger in the family photo, at age 13 or 14, than he does a year or two earlier in the barracks? Because it’s not him in the barracks, that’s why. Simply look at the difference in the forehead in the comparison of the two faces. The man in the bunk has a low hairline (short forehead). The real Naftali Fürst has a higher forehead. Thus he’s another one who succumbed to the temptation to join an exclusive club by falsely identifying himself in this famous photo. The holocaust museum people will never investigate and will never say otherwise.

Other evidence that refutes Fürst-Prince being in the photo

Naftali and his brother Shmuel (also known as Ďuro and Peter – their Slovak names) wrote a family recollection and published it sometime around 1998. In it, neither mentioned that Naftali was in the famous Buchenwald liberation photo. Naftali wrote in the Preface:

For over fifty years, my memories and emotions have been repressed deep in my soul.

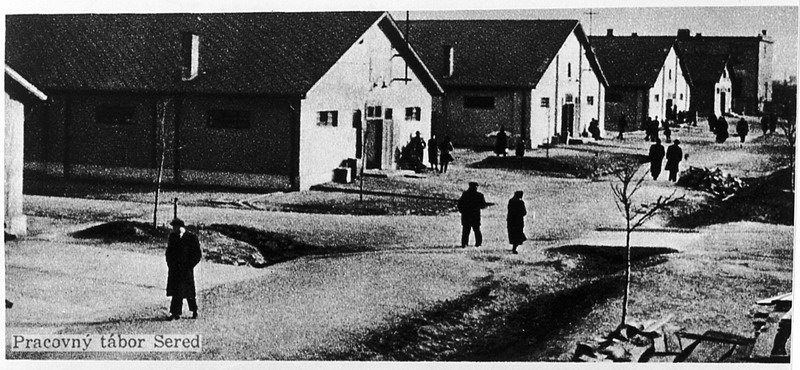

He was born in 1933; the brothers were five and seven in the fall of 1938. At the end of 1942 they moved into the Sered detention camp (photo below).

Of this, Naftali wrote that it

Of this, Naftali wrote that it

… was the most acute transition in the life of our family. We left behind a big house with a housemaid and nannies and a car, and moved into a tiny room.

Until the end of 1943, life in the camp went on in a relative stability. Until August 1944, the output of products manufactured in the camp contributed largely to the economy of Slovakia …

Beyond work, cultural events such as poetry readings, as well as soccer matches, were part of the agenda. Inside the camp, there was a small swimming pool. Every now and then we were permitted to go for a swim. Among young men and women, love affairs were flourishing.

The nearby hospital was an important institution. Prior to the war, there was a Jewish hospital in Bratislava. Its entire medical facilities were transferred to Sered. During our stay in the camp, Shmuel had an urgent appendicitis surgery in that hospital. Its proximity to the camp saved his life. By February 1944, Shmuel was thirteen years old. With great efforts and despite all obstacles, our parents managed to celebrate his Bar-Mitzvah.

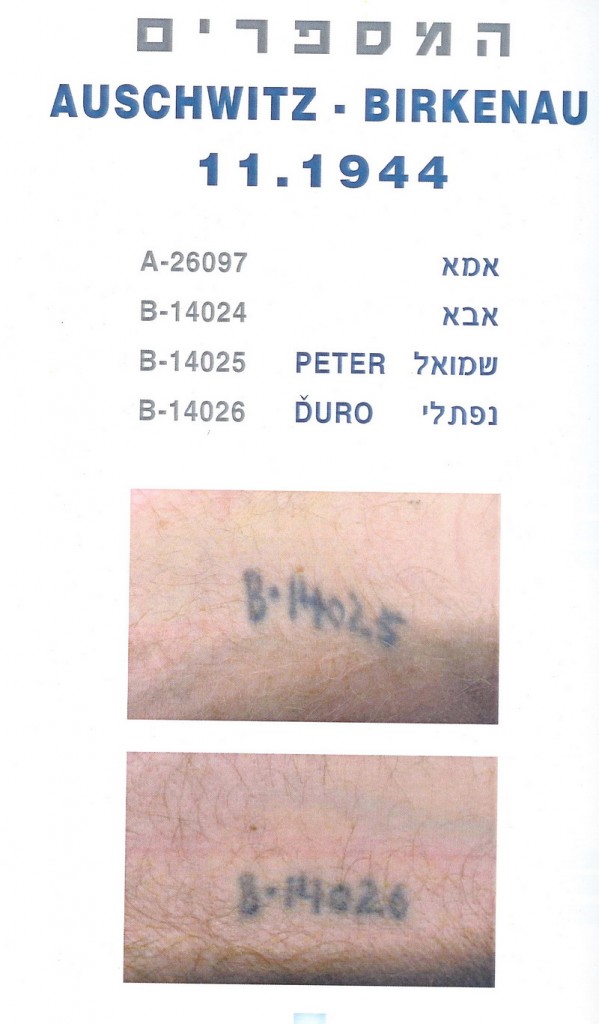

On November 2, 1944 the family was put on a train to Auschwitz-Birkenau. According to the story, the men got the following tattoos:

On November 2, 1944 the family was put on a train to Auschwitz-Birkenau. According to the story, the men got the following tattoos:

Dad’s number was 14024, Shmuel’s 14025, and mine 14026.

(The chart at right was created in Israel and may be truthful or may not; it is included in the family history.)

Move to the Kinderblock

After a short period, we were ordered to join with other children and youth, and move to the “Kinderblock”, the Children’s Block.

Naftali was just going on 12 years old and Shmuel was going on 14. In December they were moved to an agricultural farm near Auschwitz, at which there was little work for them to do.

On January 19, 1945 we were ordered to get ready for leaving the camp and a long march away. […] On the following morning, part of the farm equipment was loaded on horse-drawn wagons and the march begun: the wagons rolled in the front, while we marched behind them.

Naftali writes the march took 3 days and nights before they reached Breslau, followed by a day and a half train ride to Buchenwald. (This is considerably longer than the one-day march from Buna-Birkenau to Gleiwitz and train to Buchenwald that others described.) The brothers were eventually together in the children’s barracks, Block 66. After being there awhile, Naftali developed pneumonia and was transferred to a hospital. After recovering some, he says he was moved to a room in the Brothel where he enjoyed relative luxury. Then:

In the morning hours of April 11, 1945 we began hearing sound of artillery. While the frontline drew nearer and nearer, the underground rose up. On that very day Buchenwald was liberated. And where was I liberated? In the Buchenwald whorehouse! Not every twelve-year old child had such a privilege…

During the first days of freedom, there was a lot of disorder. As we were not allowed to leave the camp, we strolled aimlessly from one barrack to another. Then we went to see the crematorium and the torture cells, and finally we opened the clothes warehouse. There we wore SS uniforms.

It did not take long until we were organized into groups according to our countries of origin. Among the organizers was a man who pretended to be the brother of General Viest, a Slovak hero. He took care of the Czechoslovak group, Which a fortnight later was taken by trucks into Czechoslovakia. Upon our arrival in Bratislava, we were welcomed by the Jewish community, Which was already functioning.

Nothing is said about being photographed in Block 56 and having his image immediately displayed all around the world.

When did Naftali Fürst first decide he was in that photograph?

I would say it would have to be after 1998, after publishing the family story he wrote with his brother that is titled “Fürst Brothers.” Did someone suggest it to him or did his photographer’s eye detect an opportunity? As with all the others, the claim of being in this photo came many years later, not until the 1980’s or 90’s, and even into the 2000’s. There is a reason for this. Where are the pictures of them from that time? And where are the records? No one in that photograph was named at the time, so it is a free-for-all now to to claim yourself to be one of those faces.

After the war, Naftali studied photography in Bratislava and names his profession as Photographer. In 1949 he moved to Israel, where he still resides.

A passion for Remembrance and Revenge

“The 12-year-old boy in the 3rd row of the wooden bunks – that’s me,” says Naftali Fürst to anyone who will listen. In his hand he holds a famous photo that he almost always carries with him, because it has become part of his memory. “Inclusion in Buchenwald was the so-called death row,” recalls Prince. “I was so sick, almost on the other side.”

During the 7th Yad Vashem seminar of Remembrance in March 2004, Naftali Fürst told parts of his life story to a group of Austrian teachers. For nearly an hour he revealed fragments of his memories.

In the Preface to his family story, Fürst revealed his feelings that remain with him today:

Germans – I loathe the Germans of that era, particularly those who wore SS and Gestapo uniforms. Therefore, I decided to mention them only where it was absolutely necessary.

Max Hamburger and Nicholas Grüner (see previous posts on this blog), for no doubt similar reasons, are also anxious to speak about and embellish their long-ago ordeal anywhere they are invited. They receive great sympathy and have even become somewhat famous simply for being in the “famous photograph.”

“They didn’t know each other” at Buchenwald

“They didn’t know each other” at Buchenwald

Even though they all say they are in that picture taken on April 16, 1945, and Grüner and Fürst both say they stayed in the children’s Block #66, they did not know each other. The three men met for the first time when the now deceased journalist Ursula Junk brought them together on the 60th Anniversary of the liberation of Buchenwald in 2005.

On the occasion of the commemoration of Kristallnacht on November 9, 2006, they met again in Germany at the home of the artist Christiane Rohleder, in Much near Bonn. Invited by the Archivist of the Rhein-Sieg-Kries, Dr. Claudia Arndt, they each told the story of the 1945 photograph to the students — three painful biographies. If you believe it.

Brothers in spirit: Max Hamburger (from left), Nicholas Gruner and Naftali Fürst. Photo: Axel Vogel

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: Auschwitz-Birdenau Kinderblock, Breslau, brothel, Buchenwald Block 66, Buchenwald Lie-beration photo, Max Hamburger, Naftali Fürst, Naftali Prince, Nicholas Gruner, Sered detention camp,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.