Posts Tagged ‘Elie Wiesel’

Thursday, August 18th, 2011

Lightly edited on Aug. 21

Was Wiesel a strange choice?

What has Mr. Wiesel ever done for “peace” or, even more to the point, “world peace?” He was a devoted Zionist even in his youth, working as a journalist for Zion in Kampf, a Yiddish newspaper in Paris (see here). He had many contacts with the Irgun terrorist organization and cheered on their every action; he may well have been even more deeply involved with Irgun. He stated in his memoir that “I belonged to the Irgun.” He has supported every illegal military action in which Israel took over more land, homes and livelihoods of Palestinians, right up to his being an apologist for the latest unprovoked attack on Gaza in 2008-09 when the Jews used white phosphorous bombs on civilians.

Wiesel has never sought to act as a peace-maker in these ongoing unbalanced attacks, nor has he criticized or sought to stop the many wars of the United States since he became a citizen in 1963. He has also promoted a virulent anti-Germanism, e.g. “Every Jew should set aside a zone of hate – healthy, virile hate – for what the German personifies and for what persists in the German.” He has never publicly repudiated this statement.

So why was Elie Wiesel chosen for the most prestigious award in the Western world, the Nobel Prize for Peace, in 1986 when it still carried a dignified aura? (It has since lost some of that glow because so many of its recipients, including Wiesel, have lost theirs!) You’ll find the answers in the article below from The New Republic that appeared in November 1986 before the Nobel award ceremony took place on Dec. 10.

Sub-headings and photos have been added by me. -cy

Elie Wiesel gives a speech after the Nobel awarding ceremonies on December 11, 1986.

___________________

Pop Goes Elie Wiesel

How to get a Nobel prize.

by Jacob Weisberg

November 10, 1986

“I was of course very stunned and grateful, and melancholy,” Elie Wiesel told the The New York Times about his initial reaction to winning the 1986 Nobel Peace Prize. “I fell back into the mood of Yom Kippur, serious reflection about my parents and grandparents. It took me half an hour to get out of it.” But when Wiesel finally came to, he told a press conference in New York, “There are no coincidences. If it [winning the prize] happens after Yom Kippur here, then some of my friends and myself have prayed well.”

Actually, they did a little more than pray. Over the past several years, a few of Wiesel’s friends have circled the globe in an intensive effort to win him the prize. Sigmund Strochlitz (in photo below left), who owns a Ford dealership in New London, Connecticut, has directed the offensive. A survivor of Auschwitz, Strochlitz has visited the halls of Congress, the West German Bundestag, the French Assembly, and the Norwegian Parliament on Weisel’s behalf.

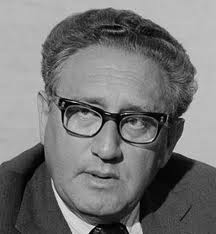

It might sound difficult to lobby for the Nobel Peace Prize. In reality, it’s not so tough. According to the rules of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, several categories of persons are eligible to make nominations. Parliamentary representatives, judges, academic, and former Nobel laureates are among those entitled to send letters of nomination to the committee in Oslo. They’re due by February 1. Strochlitz’s strategy has been to solicit these letters by the bushel. He’s succeeded in getting hundreds of them, including nominations from Francois Mitterand and former Peace prize winners Henry Kissinger, Lech Walesa, and Mother Theresa.

It might sound difficult to lobby for the Nobel Peace Prize. In reality, it’s not so tough. According to the rules of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, several categories of persons are eligible to make nominations. Parliamentary representatives, judges, academic, and former Nobel laureates are among those entitled to send letters of nomination to the committee in Oslo. They’re due by February 1. Strochlitz’s strategy has been to solicit these letters by the bushel. He’s succeeded in getting hundreds of them, including nominations from Francois Mitterand and former Peace prize winners Henry Kissinger, Lech Walesa, and Mother Theresa.

Wiesel’s supporters have concentrated much of their energy on the U.S. Senate. One Senate aide described their campaign as “relentless and heavy-handed.” “Strochlitz would show up every winter and say “it’s time to write letters again,” one staffer said. “He’d say, ‘you did it last year. It’s time to do it again.’ He’d get the senators to send ‘Dear Colleague’ letters to each other in an every-widening circle.” Strochlitz, a close friend of Wiesel’s, denies doing any campaigning.

Here’s how it worked. Strochlitz asked Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, for example, to nominate Wiesel, and to request similar letters from ten of his colleagues. Strochlitz provided Moynihan with the names. Of course, many of the legislators Moynihan asked had no idea they could nominate anyone for a Nobel Prize. And a few hardly knew who Elie Wiesel was. The letters they sent are perhaps less flowery than some the Nobel Committee has received in the past:

U.S. Senate

January 28, 1984

Members of the Committee:

It is my honor to propose Mr. Elie Wiesel for the 1984 Nobel Prize for Peace. As you well know, Mr Wiesel has dedicated most of his life toward the goal of peace throughout the world. In my opinion, you could not go wrong by awarding the Nobel Peace Prize to this most deserving gentleman.

With Respect

Barry Goldwater

By Strochlitz’s count, more than 50 senators and 140 representatives have written to Oslo on Wiesel’s behalf. More than 70 members of the West German Bundestag have also nominated Wiesel. After getting a few dozen senators under his belt, Strochlitz began grouping them in interesting ways. One year he got the entire Massachusetts congressional delegation to nominate Wiesel. Another year he solicited letters from all the members of the Senate Banking Committee.

Boston University’s John Silber helps out

Strochlitz was helped by John Silber (right), the president of Boston University, where Wiesel teaches. Silber called Strochlitz “the real strategist and campaigner.” “Strochlitz did everything in his power,” Silber said. “he would say to me: ‘John, you know these people in Congress.’ I’d write to them and send copies of their responses to Strochlitz, so he could keep track of everything we were doing.” Silber said that he is especially delighted at Wiesel finally winning the prize, since it is the second such award bestowed upon someone associated with his school. Martin Luther King, who won the Peace Prize in 1964, was a student at Boston University during the 1950’s.

Strochlitz was helped by John Silber (right), the president of Boston University, where Wiesel teaches. Silber called Strochlitz “the real strategist and campaigner.” “Strochlitz did everything in his power,” Silber said. “he would say to me: ‘John, you know these people in Congress.’ I’d write to them and send copies of their responses to Strochlitz, so he could keep track of everything we were doing.” Silber said that he is especially delighted at Wiesel finally winning the prize, since it is the second such award bestowed upon someone associated with his school. Martin Luther King, who won the Peace Prize in 1964, was a student at Boston University during the 1950’s.

In Silber’s letters to the Nobel Committee, he argued that Wiesel was not just a spokesman for survivors of the Holocaust, but a voice for victims everywhere. Each year that he re-nominated Wiesel, he wrote the committee about some new effort of Wiesel’s on behalf of the oppressed–whether his work for Cambodian boat people, or Soviet Jews, or Arab refugees, or those disappeared in Argentina. A typical letter from Silber to the committee points out that “Wiesel traveled at considerable risk to his personal health and safety into the jungles of Honduras, where he met with the Miskito Indians.” Attached was an op-ed piece Wiesel published in the Los Angeles times, detailing the Miskito’s plight. As Silber put it one year, “I am sure that my letter will not be the first, nor indeed the only such letter to reach you…”

Another of Silber’s tactics has been to suggest appropriate anniversaries for the Nobel Committee to make use of in honoring his friend. In 1984 he wrote of the connections between Wiesel and Orwell. The following year Silber’s letter reminded the committee that it was the 40th anniversary of the liberation of the death camps. Wiesel’s friends searched endlessly for a new “peg” on which to hang the same old story.

Silber said Wiesel never inquired about the effort to get him the prize, though he was aware of it. “He never asked anybody, never asked me, never asked Strochlitz,” Silber said. “We said, ‘stand still, Elie. Step aside, do your work. Don’t worry about our work, which is to make them [the Nobel Committee] aware of yours.'” Silber added, “Nobody wins unless the Nobel Committee knows about them.” Silber and Strochlitz both vociferously decline any share of the credit for Wiesel’s prize in 1986. “That would be like the trainer claiming he’s the race horse,” Silber said. “We may have fed the oats, and curried the flanks. But that horse could run.”

Wiesel gained by being a “non-controversial” selection

According to all published reports, Wiesel has been on the Nobel Committee’s short list for the past few years. And this year members of the jury thought it necessary to make a non-controversial selection. Last year’s prize, which was shared by Soviet doctor Yevgeny I. Chazov, of the Boston-based Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear war, humiliated the committee when it was revealed that Chazov had denounced laureate Andrei Sakharov several years earlier. In 1986 it was the West’s turn to be mollified.

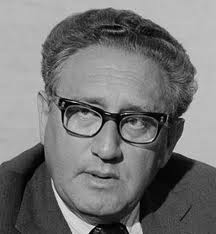

Looking down the list of past winners, one wonders what the prize is actually for. Some years it appears to reward good deeds on a large scale. Other times, it seems to honor political leadership. On a few occasions, such as 1973, when it was awarded jointly to Henry Kissinger (left ) and Le Duc Tho, it has seemed closer to a war prize than a peace prize. These days, it’s a rather amorphous accolade–sort of a moral hall of fame for the indisputably decent.

Looking down the list of past winners, one wonders what the prize is actually for. Some years it appears to reward good deeds on a large scale. Other times, it seems to honor political leadership. On a few occasions, such as 1973, when it was awarded jointly to Henry Kissinger (left ) and Le Duc Tho, it has seemed closer to a war prize than a peace prize. These days, it’s a rather amorphous accolade–sort of a moral hall of fame for the indisputably decent.

Whatever the Nobel Peace Prize signified, it’s clear that people lobby for it. Nobody seems quite sure what Japanese prime minister Eisaku Sato won his Nobel for in 1974, but it’s well known that he hired a public relations firm to help his campaign along. Jimmy Carter, Armand Hammer, and Indira Gandhi have been among the more recent campaigners who appear to have failed in drives for the prize. (Hammer reportedly once sent Ann Landers a jade necklace with a note asking if she could help him get nominated for the prize.) Mohandas Gandhi never campaigned for, and never got, the most coveted prize on planet earth.

Because the prize has such prestige, it’s a bit disquieting to discover that the winners actually wanted it. Nobody wants to think that the Mother Theresa’s of the world bid for earthly reward. In fact, Mother Theresa never did campaign for the Nobel Peace Prize. But she seems to be the exception, Elie Wiesel the rule. ~

____________________________________________________________

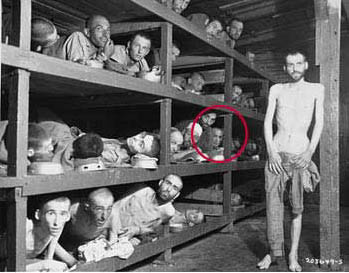

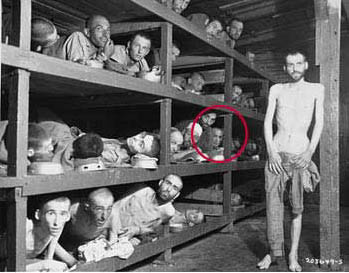

This is the photograph (in background) in which the New York Times identified Elie Wiesel, as a 16 year-old boy, for the first time in Oct. 1983 when the campaign for a Nobel Prize for Wiesel had gotten underway. In 1986, just days after winning the coveted prize following his three-year campaign, he stands in front of the photo during his visit on December 18, 1986 to the Holocaust Memorial Center ‘Yad Vashem’ in Jerusalem.

6 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: Boston University, Elie Wiesel, John Silber, Nobel Peace Prize, Sigmund Strochlitz, The New Republic,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Monday, July 18th, 2011

By Carolyn Yeager

Ken Waltzer wrote in his comment on this blog on June 27th:

“More important, Elie Wiesel’s commentary in Night bears fairly close resemblance to the actual experiences he had at Buchenwald—as recorded in camp documents.” (my italics)

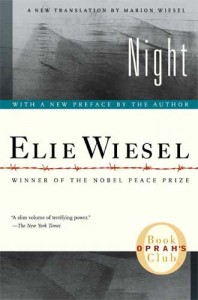

What are we to make of the words “fairly close resemblance?” According to Waltzer—and to Wiesel—Wiesel is writing down his own experience. “Every word is true!” Wiesel has said of his book Night. Thus it should exactly resemble the actual experience he had. I’m going to examine closely what is written in Night about Buchenwald to see if that is the case.

It’s not too difficult because the newest English edition of Night1—a new translation by wife Marion Wiesel which changes (corrects) some of the more blatant “boo-boos” found in the original 1960 edition—comprises only 115 pages. Of that, Wiesel’s description of his time at Buchenwald begins on page 104, giving it only 11 pages (one page being blank).

Wiesel wrote a new preface for this new translation in which he tries to answer some of the more common criticisms of his book. His answer to the differences between the Yiddish And the World Remained Silent and Night is that he cut passages he thought might be superfluous … or “too personal, too private, perhaps.” Strange thing to say since he had already published it. Concerning Buchenwald, he quotes the original writing about the death of his father, where the club-wielder is called “an SS” three times! In Night, as you will see below, this person becomes simply “an officer.” Naturally I ask: Did this scene even happen? Wiesel also tries to explain why he cut out from the ending so much of what was in the Yiddish version, but in doing so he leaves unmentioned an extensive part of what he cut. I have quoted these two endings in Shadowy Origins of Night, Part II.

Wiesel begins his experience at Buchenwald by writing that upon reaching the entrance to the Buchenwald camp along with his father and all the new arrivals from his transport, the SS counted them and they were directed to the Appelplatz (roll call area inside the camp) where loudspeakers ordered “Form ranks of fives! Groups of one hundred! Five steps forward!” He then writes, “A veteran of Buchenwald (as he puts it), told us that we would be taking a shower and afterward be sent to different blocks.” He makes it sound as if it were one of those among them, but it actually had to be a Kapo.

He writes that hundreds of prisoners crowded the shower area and made it difficult to get in, therefore his father wanted to find a place to sit down and wait—which he did in a pile of snow where there were other ‘bodies’ sticking out. Dead or alive we’re not told. It’s one of those literary scenes wherein Eliezer confronts Death via his fear of his father’s death. He writes: “This discussion (with his father) continued for some time.” Then … “sirens began to wail … lights went out … guards chased us toward the blocks.” They obviously did not get a hot shower. Wiesel adds: “The cauldrons at the entrance found no takers.” 2

Are we to believe that the kapos, or “veterans of Buchenwald,” allowed non-disinfected, non-showered new arrivals into the barracks, possibly carrying lice and other vermin with them? No way could this have happened. Yet Wiesel writes: “We let ourselves sink into the floor. To sleep was all that mattered.” I guess it was okay because they didn’t get into the beds.

In the morning, having lost track of his father the night before, he went to search for him. What about the regimentation? What about the early morning roll call? Wiesel writes: “I walked for hours without finding him. Then I came to a block where they were distributing black ‘coffee.’ ” 3 He heard his father’s voice asking for some coffee. He brought it to him. “He was lying on the boards,” meaning, I suppose, a bare bunk. Then, “We had been ordered to go outside to allow for cleaning of the blocks (barracks). Only the sick could remain inside. (If that was the case, they were not fumigating.) We stayed outside for five hours. We were given soup. When they allowed us to return to the blocks, I rushed toward my father” … who told Eliezer he had not been given any soup because “they said we would die soon and it would be a waste of food.”

Apparently, he stayed with his father in that barracks, making sure he was fed. Were they allowed to live in whatever barracks they chose? Again, there is no explanation given for this. He then writes that on the third day after their arrival everybody had to go to the showers, even the sick. Having done that (with no description of the process at all), they again had to wait “a long time” outside the barracks while they were being cleaned.

He fills a couple of pages with scenes of watching his father deteriorate amidst all the heartlessness. Then, after a week, a Blockälteste (block warden) told him he couldn’t save his father and he should help himself by eating his father’s rations. Instead, he pretends to be sick so he can stay in the barracks with his father. He doesn’t go to roll call. Now comes the famous passage in which he writes: “In front of the block, the SS were giving orders. An officer passed between the bunks. My father was pleading: “My son, water…I’m burning up…My insides …” The officer shouts at him to be quiet, walks over with a club and hits him “a violent blow to the head.” On that night, January 28, 1945, his father allegedly died.

The main problems with reality in this passage are:

1) The SS is known to have not been active inside the camp; the prisoner-trustees, usually communists, took care of giving the prisoners their orders. So the SS would not be in front of the block giving orders.

2) “An officer” can only be an SS officer. But they never came inside the barracks. Inmates, no matter how much “in charge” they might be, were not called officers. So who was this mysterious “officer” who was inside the barracks? Not SS at all; just part of the fiction and another attempt to assign brutalities to the SS.

Eliezer says he did not weep for his father. He was numb. He was transferred to the children’s block, where he remained with 600 others until April 11. That’s two and a half months, yet he tells us nothing of that time except that he did have an appetite and his only interest was getting an extra ration of soup. On April 5 (he knew the exact date) “we were inside the block, waiting for an SS to come and count us. He was late. Such lateness was unprecedented in the history of Buchenwald.”

Same problem as above: the official story (and Waltzer’s story) tells us that the communist “veterans” had these boys hidden away in the “small camp” where they cared for them, keeping them away from the SS and the camp authorities. We know that the SS did not go inside the blocks. Yet Wiesel writes that they did every day because on this day they were late. Covering for Wiesel, Waltzer writes on his website:

…the 16-year old Wiesel was assigned to a special barracks that was created and maintained by the clandestine underground resistance in the camp as part of a strategy of saving youths. This block, Block 66, was located in the deepest part of the disease-infested little camp, a separate space below the main camp at Buchenwald that was beyond the normal Nazi SS gaze (the local SS officer actively cooperated and conducted appels inside the barracks).

The barracks was overseen by block elder Antonin Kalina, a Czech Communist from Prague, and his deputy, Gustav Schiller, a Polish-Jewish Communist originally from Lvov. Odon Gati, a Communist from Budapest, was stubendienst. Schiller, who appears briefly in “Night,” was a father figure and mentor, especially for the Polish-Jewish boys and many of the Czech-Jewish boys, but he was less liked, and even feared, by Hungarian- and Romanian-Jewish boys, especially religious boys, including Wiesel. He appears in “Night” as a menacing figure, armed with a truncheon.

First, Waltzer mentions the underground. But they did not have the power to hide away the youths who were assigned to the special barracks 66. It was a policy of the Camp Commandant to separate these children to keep them safe, to feed them as well as possible, and they were fully aware of the children’s barrack 66 where they were kept. Thus. there may have been a “local SS officer” assigned to look after Block 66 to make sure everything was being done according to regulations … that is, even to supervise, to some extent, the communist block leaders. The story that it was the communists who “saved these boys from death” is a fiction that was created later, after the liberation of the camp and the formation of the Buchenwald association which was made up of former prisoners of communist persuasion. It was the camp authorities who made the decision to place the “children” away and apart from the adult prisoners, not the underground resistance.

Second, Wiesel writes in Night, “Gustav, the Blockälteste, made it clear with his club” that they had to obey the order to gather in the Appelplatz. Doesn’t this imply that the communist overseers were not necessarily acting as “father-figures” and mentors, but simply as guards? Also note that the kapo Gustav was carrying a club and used it, while earlier it was an “officer” in the barracks who wielded a club against Eliezer’s father. Relative to this, Ferenc Kornfeld reports : “Without exception, the Kapos all had big sticks.” He also said a Kapo armband went with a double food ration. And, “They continually shouted and they hit people on the head and the neck.” Kornfeld wrote about Buchenwald: “There were common criminals, murderers and thieves, in concentration camps too. They were called the “Blockältesters”. They were the “Kapos” (bosses). As they were murderers, they had black triangles on their uniforms. The Kapos hit and slapped all of us.” So much for the idea of Blockälteste’s as mentors.

The abrupt ending of Night

Wiesel claims on pages 114-15 (the last two pages of the book) that on April 5 everyone, even the children, were ordered to gather in the Appelplatz. On the way, some prisoners told them to go back because the Germans planned to shoot them. They turned around and on the way back they learned that “the underground resistance of the camp had made the decision not to abandon the Jews and to prevent their liquidation.” What kind of nonsense is this? Well, it is “the story” which evolved that these communists at Buchenwald finally, on the very last day, fought the Germans. What really happened was the Germans were ready to abandon the camp on the 11th, which they did. Wiesel simply picks up that official fiction of the underground resistance and incorporates it into his narrative. I don’t think the Germans ever intended to evacuate the children and youths.

Apparently, after the 5th, blocks of prisoners were being evacuated to other camps. By April 10, Wiesel writes, “we had not eaten for nearly six days except for a few stalks of grass and some potato peels found on the grounds of the kitchen.” From whom did these potato peels come? Did their communist keepers gather them and bring them to the youths inside the barracks? Did the boys roam around freely and eat grass? At ten o’clock the next morning, he tells us, the SS positioned themselves around the camp and began to herd the remaining inmates toward the Appelplatz. At this point the underground resistance members appeared “from everywhere” with guns and grenades. Eliezer and the other children “remained flat on the floor of the block.” (Therefore they saw nothing.) By noon, the SS had fled and the resistance was in charge. The first American tank arrived at 6 p.m.

Wiesel now wastes no time in concluding the book. He says he became very ill from food poisoning three days later because they “threw themselves on the provisions.” He spent two weeks in the hospital “between life and death.” One day he got up and looked in a mirror and saw only a corpse gazing back at him. This was at the end of April or first of May 1945. Yet he recovered so well that we see a healthy, smiling boy in the picture supposedly taken of him at Ambloy in late 1945 … or is it early or mid 1946?

It’s interesting that Wiesel made such a point later on of maintaining he had vowed in 1945 to wait ten years to write down his experiences. The reasons given, including that his memory would be sharper after ten years, are completely bogus—especially since his book bears little resemblance to the actual camps as we know them to be. The much longer Yiddish version was published in 1955-56. The abridged French version La Nuit in 1958; the English Night in 1960.

Conclusions

I have to say Wiesel doesn’t describe Buchenwald at all. You don’t know anything about Buchenwald from reading Night. You don’t learn much about Eliezer or anyone else. You are given an impression of suffering, without rhyme or reason, so Buchenwald becomes synonymous with suffering, that’s about it. We don’t know what it looks like. We don’t know the name or the physical appearance of any person, not even Gustav carrying a club, who is said elsewhere to have had red hair. Wiesel makes up a story about “an officer” using a club in the barracks when it could only be a kapo (if it was anyone at all). He doesn’t tell us anything about the children in the barracks where he stayed for 2 ½ months. He doesn’t describe the few days after liberation, before he got sick. One did not have to be at Buchenwald to write what he wrote!

Ken Waltzer also writes at his website:

Elie Wiesel has acknowledged the role played by the clandestine underground and political prisoners in saving children and youth at Buchenwald, especially in his autobiography, but he did not attend to this in “Night.” It was not his purpose or focus in that book. Many of his fellow barracks members, however, who are still alive and remember very well their days and nights in Block 66; their relations with Kalina, Schiller and others; and the hope provided to them there, have been helping fill in the story.

You can see a couple of these fellow barracks members here: Scroll down for Excerpts from the “Boys of Buchenwald” discussion panel (7.45 minutes) You can judge for yourself how impressive they are…or not. Neither one mentions Elie Wiesel.

Endnotes:

1. Elie Wiesel, Night, Hill and Wang, New York, 2006, 120 pgs.

2. This can refer to soup or disinfectant being available at the entrance to the barracks. Obviously, Eliezer and his father dawdling by having their long conversation caused them to miss out on both shower and whatever was in the cauldrons. Just another example of the intended vague descriptions permeating this book.

3. In the book, “coffee” is in quotes signifying it wasn’t real coffee. I left off the quote marks in the original writing because of the quote mark signifying the end of the sentence. Poor judgement on my part, but whether it was real coffee or not wasn’t the focus of my attention in this critique. However, the sharp attention of the author of the Scrapbookpages Blog picked up on this and wrote about Wiesel’s failure to know that real coffee was not served in the camps. My apology to “Furtherglory” for misleading him and to my readers also. I have added the quote marks since reading the blog at Scrapbookpages Blog.

17 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: And the World Remained Silent, Buchenwald, Elie Wiesel, Gustav Schiller, Ken Waltzer, Night,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Tuesday, July 12th, 2011

By Carolyn Yeager

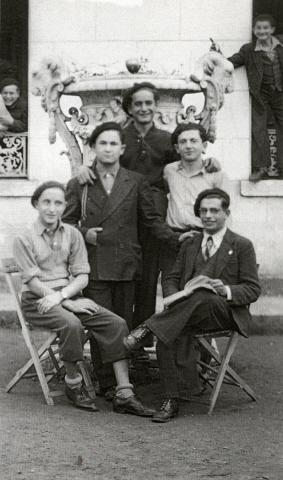

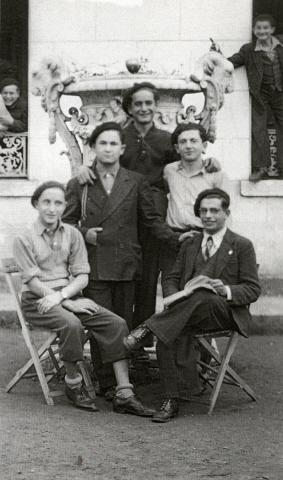

Pictured: front left, Kalman Kalikstein; Binem Wrzonski (middle right), and Elie Wiesel (back center).

This picture is now available for purchase at the USHMM website. The information about it is given as follows:

Date: 1945-1946

Locale: Ambloy (Loir-et-Cher) France

Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Binem Wrzonski

Copyright: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Title: Group portrait of boys in the Ambloy children’s home.

USHMM Commentary: In June 5, 1945, Binem joined a group of boys and young teenagers, known as “The Buchenwald Boys” who were brought to France in a special convey under the sponsorship of the O.S.E. They first were brought to Ecouis in Normandy. An aid worked (sic) helped Binem to make contact with his one surviving sibling, Towa who had spent the war in the Soviet Union. From Ecouis the children were taken to either secular or religious homes. Binem at first wanted to go to a secular home, but Leo Margolis, a German Jew who was in Buchenwald for approximately six years and helped care for the children, persuaded him to go to a religious home. Binem then went to Chateau d’Ambloy. From there he went to Taverny. Then together with two other teenagers, with Elie Wiesel and Kalman Kaliksztajn, he accompanied a group of younger boys to Chez Nous in Versailles where worked as a counselor. From this experience, Binem decided to become a teacher. After training in France, he immigrated to Israel and became the principal of a Youth Aliyah boarding school. In Israel he met and married Rahel Schlezinger and they went on to have five children and many grandchildren and great-grandchildren. In 1983 Binem returned to Lodz and erected a new marker at his father’s graves including the names of all of his family members who died during the Holocaust. [end of USHMM commentary]

* * * *

Binem came from Buchenwald, but not Elie Wiesel and maybe not his good friend Kalman!

What is amazing about this commentary on the picture above is that Elie Wiesel is NOT said to have been at Buchenwald with Binem, but encountered him at Taverny. Elie and Kalman, according to Binem, accompanied a group of younger boys to Chez Nous in Versailles where they worked as counselors. This actually makes a lot more sense. A narrative in which Elie Wiesel is not a withdrawn, scarred youth from the concentration camps, but possibly arrived in France sometime during the war—helped by the Jewish network and placed in the children’s welfare institutions—is quite possible. There, he associated with some of the youths who were sent after the war, and developed his “knowledge” of concentration camp life from them.

Is this why he had no interest in gaining French citizenship—because he was devoted to the Jewish cause of Eretz Israel and always connected to and working with the Jewish Underground? (See Elie Wiesel and the Mossad)

Was Elie Wiesel actually a youth counselor for Buchenwald boys, rather than one of them?

Can this explain why he remained with the welfare agencies for so long and was one of the oldest to leave his last home at Versailles to live on his own? His friend Kalman left for Israel in 1947 before Elie managed to get a room of his own “at the end of summer” at the age of 19. This would have been after his birthday on Sept. 30.

Compare this photograph with the one below, which the USHMM identifies as:

Group portrait of the staff and boys of Ambloy, an OSE home for religious youth.

Among those pictured are (First row, left to right): Natan Szwarc, Izio Rosenman, Deblin, unknown and perhaps Berek Rybsztajn. (Third row): Abraham Tuszynsky (2nd from left, first boy next to woman), Andre Zelig is in the center with a tie and his hands on the boy in front of him and Elie Wiesel (second right of Tuszynsky). Binem Wrzonski is to the right of Elie Wiesel. The donor, Jakob Rybsztajn is in the fourth row, fifth from the left.

This picture is available for purchase from USHMM website. The information given about it is as follows:

Date: 1945

Locale: Ambloy, (Loir-et-Cher) France

Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Jacques Ribons

Copyright: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

The inscription on the back reads “Before our departure from Chateau Ambloy for Paris.”

USHMM Commentary: Jakob Rybsztajn (now Jacques Ribons) is the son of Peretz Rybsztajn (b. 1905) and Bella (Bajal, b. 1906) Rybsztajn. He was born on August 15, 1927 in Strzemieszyce Poland where his father was a textile manufacturer. He had two younger siblings: Bernard (Berek) who was born in 1929 and Esther who was born in 1935. In 1933 the family moved to Zelow, Bella’s home town. The family remained there until 1936 when it moved back to Strzemieszyce. In 1939 Germany invaded Poland later the Rybsztajns were forced to move to a ghetto. Jakob attended a ghetto Hebrew school. Peretz Rybsztajn, his father, worked with or was close with the Jewish Council but he soon disappeared. After the ghetto was liquidated, probably in June 1943, Jakob and Berek, who initially had hid, were forced to return and then sent briefly to Bedzin. In September they were deported to the Blechhammer concentration camp where they were forced to work unloading cement from train cars, insulating oil and fuel tanks with asbestos, and cementing steel forms to the tanks. They lived in a barrack with other boys their ages, including Kalman and Heniek Kaliksztajn, two brothers also from Strzemieszyce. In January 1945 the Germans liquidated the camp in advance of the Soviet army, and the brothers were sent on a death march via Gross Rosen and by open train to Buchenwald. They arrived in Buchenwald on February 10, 1945, and were placed in the children’s block, Block 66.

Jakob and Berek remained together in block 66 until they were liberated in Buchenwald by the U.S. Third Army in April. The boys in the barrack, under the supervision of Gustav Schiller, the deputy block elder, did not work and received occasional Red Cross packages distributed from other prisoners in the camp. After liberation, the Rybsztajn brothers joined a children’s transport to Ecouis in France, sponsored by the O.S.E., where they were through the summer. But, as they were religious, they were sent from there with other religious boys, including the Kaliksztajn brothers, also Elie Wiesel, to children’s homes in Ambloy and Taverny. Then Jacques came to Paterson New Jersey and later enlisted in US army during the Korean conflict. He arrived in New York in February 1947 on board the Gripsholn, a Swedish ship. Berek was adopted by the Homberger family in California. Later he was in Israel and served in the Israeli Defense Forces; he returned to California in the late 1950s. Jacques also settled in Los Angeles. The Rybsztajn parents, Perez and Bella Rybsztajn, and their sister younger sister Esther perished in Auschwitz, it is believed, during 1943. [end of USHMM commentary]

* * * *

If it can be proven that this is indeed Elie Wiesel in the two pictures, we still do not know if he arrived in Ambloy from Buchenwald.

We have learned that others were there already and the Buchenwald boys joined them. He may have been one of those who were already there. The commentary states as an afterthought that “also Elie Wiesel” was among those sent to Ambloy and Taverny. Where are the records that must have existed? In what capacity was Elie Wiesel there?

The person identified in each photo above as Elie Wiesel is dressed in the same clothing, so the pictures were most likely taken on the same day. The boy Binem may simply have taken off his jacket in the more casual top picture. But where is Kalman in the large group photo? He is not identified and appears to be missing. Rather than pictures on more than one occasion, we have two different pictures taken at the same time.

The group is dressed for travel to Paris (Versailles). It must have been later than 1945 that they transferred to the home in Versailles, so this picture should probably be dated 1946, as is the top picture. All of these questions I raise show the poor scholarship done by the USHMM and the holocaust historians in general. Slip-shod reporting is picked up from here and there, thrown together, becoming the “story” that fits the bill. Thus we have Elie Wiesel’s name stuck in where they want it to be, to try to show that he was one of the Buchenwald boys, when actual proof doesn’t exist.

These photographs only portray someone who could be Elie Wiesel at a home in Ambloy, France where some of the boys from Buchenwald, and also Jewish boys from elsewhere, lived for a time.

As far as the next picture is concerned, I now cannot be sure that these boys are arriving from Buchenwald. They are only identified as Jewish DP (displaced persons) youth at the USHMM website:

Group portrait of Jewish DP youth at the OSE (Oeuvre de Secours aux Enfants) home for Orthodox Jewish children in Ambloy. Elie Wiesel is among those pictured. [Photograph #28147]

This photo is also available for purchase at USHMM website. The information given about it is as follows:

Date: 1945

Locale: Ambloy, (Loir-et-Cher) France

Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Robert Waisman. Willy Fogel

Copyright: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

In this case, none of the boys are identified by name. In the long commentary that accompanies the picture on the page, there is no mention at all of Elie Wiesel. I will say that no one in this picture is wearing a beret! Once again, if the USHMM or Prof. Ken Waltzer claim that Elie Wiesel is in this picture, they must point him out.

It has never been disputed that Elie Wiesel was in France. But just when he arrived and what he was doing there is not documented.

* * * *

The next step for the reader is to compare the face of “Elie Wiesel” in the first two photos above with the faces of “Elie Wiesel” in the famous Buchenwald photo and the boys marching out of the Buchenwald gate, plus his portrait as a 15-year-old, that are found at “The Many Faces of Elie Wiesel.” They can’t all be Elie Wiesel. It’s up to you—and up to USHMM and Ken Waltzer, and how about the old liar Elie Wiesel himself!—to decide and announce which ones are. When that is clear, we can then decide what the pictures are telling us.

10 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: Ambloy, Binem Wrzonski, Buchenwald, Elie Wiesel, Jacques Ribons, USHMM,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Thursday, June 30th, 2011

By Carolyn Yeager

(Last edited on July 3 and added to on July 9)

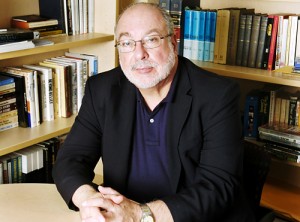

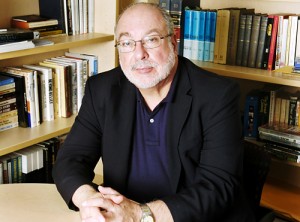

In my previous blog of June 14, I asked the question “What happened to Waltzer’s book about the ‘boys of Buchenwald?’” On June 27, Ken Waltzer (pictured right) answered me … sort of. He said he was not having any trouble with the book, but he didn’t say when we could expect to read it. Not a word on that. But he assured Elie Wiesel Cons the World readers that we will find it a powerful story when we do.

In my previous blog of June 14, I asked the question “What happened to Waltzer’s book about the ‘boys of Buchenwald?’” On June 27, Ken Waltzer (pictured right) answered me … sort of. He said he was not having any trouble with the book, but he didn’t say when we could expect to read it. Not a word on that. But he assured Elie Wiesel Cons the World readers that we will find it a powerful story when we do.

Being a person who likes to stick with the practical and real, I’m not satisfied with Prof. Waltzer’s answer because it avoids the real questions in favor of repeating his claims without supporting them. On top of that, he called me a bigot. This is a grievous fault, it seems to me, in a man who is a Professor of Jewish Studies and German History at Michigan State University. Let’s take a look at what he’s said.

Before writing a comment to my blog, Waltzer first wrote a comment on June 26 to Scrapbookpages Blog. The blogmaster there, who goes by the name of “furtherglory,” had blogged June 16 on my ‘boys of Buchenwald’ article. He checks out new articles about Holocaust on the Internet daily, and seems pretty interested in Elie Wiesel. He added an update to the original blog and asked the question: “Has Ken Waltzer finally figured out that there were three separate people involved in this controversy and all three are named Wiesel.” No, he hasn’t. Waltzer continues to insist that they are all Elie Wiesel.

This is what Ken Waltzer said on Scrapbookpages Blog:

All the ridiculous claims that Wiesel was not Wiesel, Wiesel was not at Buchenwald, Wiesel was a different Wiesel are false, There was one Lazar Wiesel at Buchenwald. He arrived with his father, who appears as Abram, born 1900, and who died shortly after arrival. (He signs his name Shlomo.) Wiesel was then moved to block 66, the children’s block, part of a large child-saving operation by people aligned with the German-Communist led international underground in the camp. He is there with others from Sighet who affirm he is there. He is there until liberation. He is interviewed by American military authorities there. He goes to France.,…

There is no question, indeed there is firm proof, Elie Wiesel was at Buchenwald. And the sections of Night written about Buchenwald are generally accurate and conform to the experience he had.

Comment by Ken Waltzer — June 26, 2011 @ 6:53 am

And this is what Furtherglory said in reply:

Thanks for your comment. A man named Lazar Wiesel was given the tattoo number A-7713 at Auschwitz. A man named Abram Viesel was given the number A-7712 at Auschwitz. Both of them were transferred to Buchenwald in January 1945. Lazar Wiesel, born at Maromarossiget on 4 September 1913, an apprentice locksmith, political detainee and Hungarian Jew, was registered at Buchenwald on 26 January 1945 and assigned the ID number 123565. This must be the man whom you have identified as Elie Wiesel and Abram Viesel is the man that you have identified as Elie’s father. In the records at Auschwitz, Abram Viesel was born on 10 October 1900 at Marmarosz. He was old enough to be Elie Wiesel’s father, but not old enough to be the father of Lazar Wiesel, who was born in 1913, according to the records.

Elie’s full name is Eliezer Wiesel and he was born in Sighet, Romania (Marmarossiget) which was a part of Hungary in 1944. Elie claims he was born on September 30, 1928. Are you saying that his birthdate was mistakenly written as Sept 4, 1913 at Buchenwald?

A man named Lázár Wiesel, (note difference in spelling) born 4 October 1928, was also registered at Buchenwald and given the ID Number 123165. Are you saying that this man did not exist?

You wrote that Elie Wiesel (Lazar Wiesel) was interviewed by the American military. Lázár Wiesel filled out a US Army questionaire on 22 April 1945 at Buchenwald; he stated on the questionaire that he was born at Màromarossziget on 4 October 1928; he was a student who was arrested on 16 April 1944 and interned at Auschwitz and Monowitz. Are you saying that this man didn’t exist?

The records at the Buchenwald Gedenkstätte show that Lázár Wiesel was sent to Paris on 16 July 1945 with a convoy of surviving children and is registered on the transport list. The name Lazar Wiesel is not on the transport list to Paris, which makes sense since he was born in 1913.

Lazar Wiesel’s name was on the transport list from Auschwitz to Buchenwald, but the name Lázár Wiesel was not. That doesn’t mean that Lázár was never at Auschwitz. He could have been sent, from Auschwitz, to some other camp, such as Gross Rosen, and then sent to Buchenwald when Gross Rosen, or whatever other camp, was evacuated.

Comment by furtherglory — June 26, 2011 @ 3:40 pm

It didn’t take furtherglory long to answer Prof. Waltzer and I thought he did a fantastic job. I mean, he’s got it all right and in order and that’s why I’m copying it here … so I won’t have to do it myself. Furtherglory asked Prof. Waltzer some questions, but Waltzer has not yet answered them. I have a feeling he won’t, either, because he doesn’t like to answer questions that he hasn’t posed himself, or are not easy ones. You see, Waltzer spends most of his time talking to his brainwashed students or to Jewish people at Jewish group events, like at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum. Did you know that Jews run that museum and make up most of the attendees at its events? See here. They never ask tough questions.

But still, I was very happy to find a comment on my blog from Prof. Waltzer and I thank him for it. I think it says a lot for him that he is willing to engage, even if only to this extent. He wrote:

by Ken Waltzer On June 27, 2011 at 2:26 pm

Carolyn Yeager suspects that Ken Waltzer is having trouble with his Buchenwald book, esp. proving Elie Wiesel was at Buchenwald as he says he was. Nothing could be further from the truth.

The Buchenwald book is drawn on survivors’ experiences interviewed around the world and on documents from the Red Cross ITS and it will tell a powerful story of endurance and rescue inside Buchenwald.

And related to that larger story, in which Elie Wiesel is merely one of many boys who were helped and saved inside Buchenwald, there simply is no mystery whatsoever of Elie Wiesel, as Yeager claims. He arrived from Buna on a terrible transport on Jan. 26, 1945, with many others (including Miklos Gruner); he was accompanied by his father, who was recorded as Abram (but who signed his name as Shlomo); they were initially together in a barrack in the little camp, 59, I think, and then — after his father died — Elie Wiesel was moved in early February to block 66, the kinderblock. Miklos Gruner too was in block 66. Elie Wiesel was there with other boys from Sighet, who knew him; he was interviewed by military authorities after liberation, in order to permit departure from the camp; and he went after liberation in early June, 1945, to France, to Ecouis…. one among 425 boys who did so. He appears in subsequent pictures at Ambloy and Taverny where the religious boys were taken after Ecouis….

More important, Elie Wiesel’s commentary in Night bears fairly close resemblance to the actual experiences he had at Buchenwald — as recorded in camp documents.

He is the truth teller — Carolyn Yeager; you are the dealer in false claims and bigoted charges.

I am a bigot for doubting Elie Wiesel. I guess it’s some form of antisemitism to doubt that every word Elie Wiesel says is absolutely true … because he is the truth teller, according to Waltzer. And he, Waltzer, is going to prove it.

I consider what Prof. Waltzer is doing similar to ‘sleight of hand.’ He‘s repeating what he’s been saying all along … with a few convenient omissions (for example, the paper proving it he promised 6 months ago). We are to believe that 1) Eliezer Wiesel was listed as Lazar when he arrived, and then as Lázár Wiesel after liberation, with the wrong birth date both times; 2) his father Shlomo was recorded as Abram, also with the wrong birth date; 3) Shlomo is short for Abram or Abraham, not Solomon; and 4) those crazy, mixed-up Nazis got their records wrong.

Has Waltzer managed to falsify some document to show that the elder Wiesel was also known at times as Abraham? We’ll see. Then there is the problem with the pictures. He hasn’t told us which of these boys arriving at Ecouis in France in 1945 is Elie Wiesel. The USHMM tells us Elie is in this picture but doesn’t say where. Can you find him?

He also didn’t point out to us which of these ‘religious boys’ is Elie Wiesel. He titled it “In France — religious boys, including Elie Wiesel.” But how can we be sure?

What he seems to be doing is moving the attention away from these pictures to others of Elie Wiesel at Ambloy and Taverny. If there are such pictures I have never seen them. Have they been newly created? Why keep them hidden all these many years? (post note: See Comments #1,2 and 3) Does this mean that Waltzer is now declining to say that Wiesel appears in the famous Buchenwald photo (below)?

Or in this photo of the boys marching out of Buchenwald after liberation—which he has claimed for several years?

Prof. Waltzer, I know you consider yourself one of the privileged of the world, along with Elie Wiesel, but you must realize that even people of such privilege as yourselves cannot just change Shlomo to Abram as it suits you. When all others who were ‘liberated’ from the German camps are identified by matching their names, birth dates, and prisoner numbers, you cannot decide that in certain cases this formula does not apply and it is YOU who decides who is who.

From your comments, I’m expecting that when your book does finally come out, it will say that Shlomo is Abram and birth dates don’t matter, and this will be a small portion of the book overshadowed by other “powerful” stories of Jewish children. There may be no pictures of Elie Wiesel in France because he is just one of many in your powerful story. It will receive praise, coordinated in advance, from the Jewish media and academic class and no concern whatsoever will be expressed about any contradiction with the facts as they are contained in the Buchenwald archival documents.

But there will be one entity that will not let you alone or off the hook, and that is Elie Wiesel Cons The World website, and maybe some of our readers and followers. So I say—thanks for the comment but we are still waiting and watching for clarification from you.

UPDATE (July 1st):

Shlomo Wiesel was never at Auschwitz or Buchenwald. If he had been at Auschwitz there would be a record for a man named Solomon Viezel or Wiesel born in 1894, who was 50 years old in 1944.

>>We read in Frank N. Magill, ed., “Great Events from History II: Arts And Culture Series: Volume 4, 1955-1969“, Salem Press, Inc., Pasadena, CA., 1993, p. 1700:

“SHLOMO WIESEL (1894-1945), the father of Elie Wiesel“

>>And in in Michaël de Saint Cheron, “Elie Wiesel : L’homme de la mémoire“, Paris, Bayard (coll. Biographie), 1998, p. 25:

“Quant à son père, Shlomo, il ne fut vraiment proche de lui que dans les camps, ces lieux hors du temps, hors de l’espace des vivants, où ils partagèrent le même sort, le même enfer, ou presque.

Son père, né en 1894, à Màrmarossziget, était un juif tolérant et éclairé, alors que sa mère, née en 1898 à Bocsko, cadette de six enfants devenue orpheline de bonne heure, très pieuse, (Translation: His father Shlomo, born in 1894, in Marmarossziget, and his mother, born in 1898 in Bocsko.)

>>More importantly, Elie Wiesel filled out a form for the Yad Vashem Memorial in Israel sometime after the year 2000 (as my memory serves me) stating his father died as a holocaust victim.** On that form, he gave his father’s name as: Shlomo Vizel. He didn’t give a date of birth, but he gave a date of death as Jan. 27, 1945 and the cause of death as: Disease. He signed himself as Eli Vizel, son. That form can be viewed at the Yad Vashem archives online; that’s where I saw it.

Nowhere has Shlomo Vizel (Wiesel) ever been called Abram or Abraham, except now by Ken Waltzer in order to fit with the records for Lazar and Abram Wiesel at Buchenwald.

Stealing real victims and survivors identity is one of the lowest forms of behavior, according to holocaust survivor groups … or so they say. What do you think?

** It should be noted that Elie Wiesel did not fill out Yad Vashem forms for his mother or youngest sister affirming them as victims of the Holocaust. Why not? The logical reason is that he does not have any knowledge that they were indeed taken immediately to a “gas chamber” and killed, as the story has been put out for public comsumption. Even on Wiesel’s main page at Wikipedia it says they were “presumably killed.” That is all. Neither did his two older sisters, who were supposedly at Auschwitz for several months before being transferred to a sub-camp of Dachau, fill out this form for their mother and sister even though they are said to have been all together in the women’s line. These two surviving sisters were totally silent about their WWII experience, in spite of their famous brother, until Hilda, the eldest, gave a videotaped testimony to Steven Spielberg’s Shoah Foundation in the 1990’s.

12 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: Abram Viesel, Boys from Buchenwald, Carolyn Yeager, Elie Wiesel, Ken Waltzer, Lazar Wiesel, Scrapbookpages Blog, Shlomo Viezel,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Tuesday, June 14th, 2011

by Carolyn Yeager

MSU Prof. Kenneth Waltzer has been promising his book The Rescue of Children and Youth in Buchenwald since 2007. Four years later, he’s being very quiet about it.

Here is a timeline of announcements about this work in progress, all taken from his Michigan State University website.

May 2005: Professor Waltzer presented a paper, “The Rescue of Children at Buchenwald: Behavior in a Grey Area,” at the Midwest Jewish Studies Scholars Colloquium, Cohn-Haddow Judaic Studies Program, Wayne State University, Detroit.

March 2007: Ken Waltzer will present a paper on “The Kovno Boys: Survival at Auschwitz, Buchenwald, and Mauthaussen,” at the 37th Annual Holocaust Scholars Conference in Cleveland, Ohio.

April 2007: Ken Waltzer presents on his book-in-progress, The Rescue of Children and Youth in Buchenwald, at James Madison College.

May 2008: MSU Professor Ken Waltzer gave the Monna and Otto Weinmann Lecture at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum on the subject of his upcoming book on the rescue operation at Buchenwald that he said saved the lives of hundreds of children and youths.

April 2010: Kenneth Waltzer, professor of history and director of the Jewish studies program at Michigan State University, is currently completing a book about the rescue of children and youths at Buchenwald. [From the April 16, 2010 The Jewish Daily Forward]

The Elie Wiesel Problem

Prof. Waltzer has written and shown pictures of himself (right) doing research at Bad Arolson in Germany, seeking to discover details about the lives and families of the boys of Buchenwald. One of the boys that he may be having trouble with is Elie Wiesel. Waltzer has made a lot of claims and put himself on the line about Wiesel that, in this writer’s opinion, cannot be substantiated.

Prof. Waltzer has written and shown pictures of himself (right) doing research at Bad Arolson in Germany, seeking to discover details about the lives and families of the boys of Buchenwald. One of the boys that he may be having trouble with is Elie Wiesel. Waltzer has made a lot of claims and put himself on the line about Wiesel that, in this writer’s opinion, cannot be substantiated.

For example, last November Waltzer commented on this website to my article “Signatures Prove Lázár Wiesel is not Elie Wiesel” with the following:

Contrary to Carolyn Yeager’s wishful thinking, Eli Wiesel was indeed the Lazar Wiesel who was admitted to Buchenwald on January 26, 1945, who was subsequently shifted to block 66, and who was interviewed by military authorities before being permitted to leave Buchenwald to go with other Buchenwald orphans to France. Furthermore, there is not a shadow of a doubt about this, although the Buchenwald records do erroneously contain — on some pieces — the birth date of 1913 rather than 1928. A forthcoming paper resolves the “riddle of Lazar” and indicates that Miklos Gruner’s Stolen Identity is a set of false charges and attack on Wiesel without any foundation. ~~ by kenwaltzer on November 14, 2010 at 10:34 am

The birthdate on Lazar Wiesel’s records is erroneous—that’s his answer? He is going to “resolve” that? The “forthcoming paper” has not yet appeared 7 months later. His website pages have not been updated for awhile; in fact, they look downright dormant.

Here are the problems I think Waltzer is having, in addition to the birthdate problem:

- He has claimed for at least several years that a picture he has placed on his website of the boys walking out of the Buchenwald front gate shows Elie Wiesel “toward the left.” [See The Many Faces of Elie Wiesel] I say it is not Elie Wiesel, and I don’t know anyone but Waltzer who has identified this boy as Elie Wiesel. This picture is also shown on the USHMM website, and they make no mention of Elie Wiesel as one of the boys.

- In a Power Point presentation that is available on his website, Waltzer shows a group picture of the ‘religious boys’ out of those who went to France, that he says includes Elie Wiesel. I have studied this picture closely and do not see anyone who resembles Wiesel. If Waltzer knows that Elie Wiesel is in the picture, why doesn’t he identify him with an arrow?

Famous Buchenwald Liberation photo is another problem

As I pointed out in “The Many Faces of Elie Wiesel,” the pictures that Waltzer claims contain the face and person of Elie Wiesel do not resemble each other. The famous barracks photo which the New York Times declared to be Elie Wiesel as a 16-year old Buchenwald inmate—and is reproduced all over the world as Elie Wiesel—doesn’t look like the other 16-year old faces.

This writer suspects that Ken Waltzer is having difficulty convincingly incorporating Elie Wiesel into the story of the “boys of Buchenwald” and their rescue. He has been a friend and devotee of Wiesel for many years, they are both strongly associated with the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, and Wiesel has been a part of his Buchenwald story from the beginning. But the real evidence for Elie Wiesel ever being an inmate at Buchenwald doesn’t exist. There are no photographs of Elie Wiesel at Buchenwald; there are no photos of Wiesel during his supposed one-year concentration camp period at all.

I think Waltzer believed this slipshod approach he employs would pass without comment, but he didn’t count on the appearance of Elie Wiesel Cons the World website. We are a real problem for Ken Waltzer!

10 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: Bad Arolson, Boys from Buchenwald, Elie Wiesel, Kenneth Waltzer, Michigan State University, New York Times, USHMM,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Wednesday, May 11th, 2011

Above: U.S. President Barack Obama with U.S. Holocaust Memorial Council Chairman Fred Zeidman (L), Elie Wiesel (2nd from R) and Holocaust Memorial Museum Director Sara Bloomfield (R) at the “Holocaust Days Of Remembrance” ceremony in the Rotunda of the U.S. Capitol April 23, 2009 in Washington, DC. Established in 1993, the Days of Remembrance are commemorated in April so that they coincide with the observance in Israel. (Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

By Carolyn Yeager

It has just been announced that Elie Wiesel will be the recipient of the FIRST U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum Award. Not a surprise. Wiesel is the one upon whom the “Holocaust Industry” feels safe in heaping praise, therefore he has enough “distinguished service” type awards to wallpaper a room.

What has he done to actually deserve them? He has been in the service of the outlaw state of Israel for most of his long life, condoning the dispossession of the native Palestinian people, and even their destruction by napalm bombing and massacres carried out on a regular basis. He’s not really a very good liar, although a prolific one, and so his self-created life story is not convincing to a mind that has even a little bit of critical capacity.

If we search earnestly for what this man has actually accomplished, we find a mixture of self-promotion and Holocaust “memory” promotion. In other words, Wiesel is a promoter. He’s made his name synonomous with The Holocaust. Of course, he’s been helped in this by powerful organizations, not least of which is the New York Times Corporation. That is a story that is yet to be told on this website, but it has been well-explored by Prof. David O’Connell in his article “Elie Wiesel and the Catholics.”

Wiesel’s so-called “humanitarian work” has been directed almost exclusively to help Jews and Jewish causes. He makes statements now and then about other groups, such as Africans in Darfur, but mostly ignores all those who are currently in distress in the world today in favor of receiving large sums of money to speak about the Jewish past. He will be doing the same when he receives the award from the USHMM on May 16 – an award that may very well have a sum of money attached to it. Money, by the way, that will be coming from the pockets of U.S. taxpayers!

Instead of celebrating this whole hypocritical affair, we should be sickened by it. According to USHMM director Sara Bloomfield, right, (see Bradley Smith’s youtube conversation with Sara), who will present the award, “no one else has done so much (as Wiesel) to honor the victims of the Holocaust by working tirelessly to create a more just world in their memory.” Hmmm. Once again, a more just world for Jews. She explains he does this by his “conviction that the Museum should be a ‘living’ memorial.” She doesn’t explain what makes it ‘living’ and don’t expect her to. These are just words that are designed to stir emotions or good feelings in the hearer, and is what they expect. By such words we are to accept that “His legacy to humanity is unique and extraordinary.” Just don’t ask questions.

Instead of celebrating this whole hypocritical affair, we should be sickened by it. According to USHMM director Sara Bloomfield, right, (see Bradley Smith’s youtube conversation with Sara), who will present the award, “no one else has done so much (as Wiesel) to honor the victims of the Holocaust by working tirelessly to create a more just world in their memory.” Hmmm. Once again, a more just world for Jews. She explains he does this by his “conviction that the Museum should be a ‘living’ memorial.” She doesn’t explain what makes it ‘living’ and don’t expect her to. These are just words that are designed to stir emotions or good feelings in the hearer, and is what they expect. By such words we are to accept that “His legacy to humanity is unique and extraordinary.” Just don’t ask questions.

Those lucky enough to attend this dinner will also be able to hear Deborah Lipstadt, left, who will give a speech to promote her new book The Eichmann Trial. In fact, this year of 2011 was picked for the first award because it is the 65th anniversary of the verdicts at the first Nuremberg trial and the 50th anniversary of the trial of Adolf Eichmann. They can’t let “memory” die out, you know. And there is also that need to mark anniversaries of the most sacred dates in the Holocaust religious calendar.

Those lucky enough to attend this dinner will also be able to hear Deborah Lipstadt, left, who will give a speech to promote her new book The Eichmann Trial. In fact, this year of 2011 was picked for the first award because it is the 65th anniversary of the verdicts at the first Nuremberg trial and the 50th anniversary of the trial of Adolf Eichmann. They can’t let “memory” die out, you know. And there is also that need to mark anniversaries of the most sacred dates in the Holocaust religious calendar.

P.S. A postscript to Seven-up: Here is your chance to leaflet a Wiesel event in person. Hop on a plane and get yourself to the Wardman Park Marriott Hotel in Wash. D.C. by May 16th and you’ve got it made. Remember, you can download leaflets questioning Wiesel’s tattoo by clicking on the Downloads button on our menu bar—if you don’t have any leaflets of your own. Good luck and let us know how it went.

9 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: Barack Obama, Deborah Lipstadt, Elie Wiesel, Sara Bloomfield, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Sunday, May 1st, 2011

by Carolyn Yeager

Today, May 1st, Elie Wiesel Cons The World received the 17th comment on the blogpost “Is Elie Wiesel a perjurer?” This is the most comments for any article posted here except for our very first “Welcome” blog .

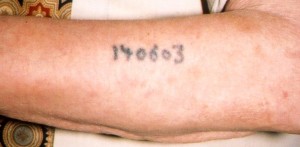

Six ‘believers’ were disturbed enough by this article to write a comment scolding us for it. This tells me that the idea that Elie Wiesel does not have a tattoo, yet says he does, is the most worrisome issue for believers. They get angry when faced with the proof that Elie Wiesel tells lies. They have no way to talk around it.

Realizing this, I am re-posting that article with some added material which I have put in brackets []. This version of the article should be circulated as widely as possible to the mainstream media and mainstream commentators by those of you who want to see some action on this.

Written on August 24, 2010 at 10:01 am, by Carolyn Yeager

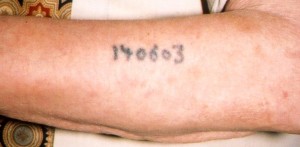

Elie Wiesel stated under oath while giving testimony in the trial of Eric Hunt in San Francisco, California in July 2008 that the number A7713 was tattooed on his left arm. (see Where is the Tattoo?)

Wiesel should have been asked to show his tattoo to the court at that time, but he wasn’t. This was a failure of the defense, for sure. But obviously, at that time, Mr. Hunt, the defendant, was not questioning whether Elie Wiesel had been an inmate of Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Since then, Mr. Hunt and others have uncovered video photography of Wiesel’s bare left arm from all angles, leaving no reasonable doubt that no tattoo is there. Backing up this conclusion is the fact that Wiesel has also famously refused to ever show his tattoo when requested to do so. For those who will retaliate that Wiesel may have had the tattoo removed, he said as late as March 25, 2010 that he still had the number A7713 on his arm. (see Where is the Tattoo?) [In September or October 2012, AP reporter Verena Dobnik wrote in a published news report that Elie Wiesel showed her his tattoo during an interview. Wiesel has never denied the story.]

From this, the average man on the street would probably agree that Elie Wiesel has committed perjury (a criminal offense) if he does not indeed have the number tattooed on his arm. The law, according to http://www.lectlaw.com/def2/p032.htm, says:

When a person, having taken an oath before a competent tribunal, officer, or person, in any case in which a law of the U.S. authorizes an oath to be administered, that he will testify, declare, depose, or certify truly, or that any written testimony, declaration, deposition, or certificate by him subscribed, is true, willfully and contrary to such oath states or subscribes any material matter which he does not believe to be true; or in any declaration, certificate, verification, or statement under penalty of perjury, willfully subscribes as true any material matter which he does not believe to be true; (18 USC )

In order for a person to be found guilty of perjury the government must prove: the person testified under oath before [e.g., the grand jury]; at least one particular statement was false; and the person knew at the time the testimony was false.

[Under the law, Elie Wiesel did knowingly lie to the court about a tattoo on his arm.] However, in practice, the question of materiality is crucial. Perjury is defined at www.criminal-law.freeadvice.com as:

the “willful and corrupt taking of a false oath in regard to a material matter in a judicial proceeding.” It is sometimes called “lying under oath;” that is, deliberately telling a lie in a courtroom proceeding after having taken an oath to tell the truth. It is important that the false statement be material to the case at hand—that it could affect the outcome of the case. It is not considered perjury, for example, to lie about your age, unless your age is a key factor in proving the case.

So the question becomes: Was the status of Elie Wiesel as a survivor of at least a seven-month incarceration at Auschwitz-Birkenau in 1944-45, in which case he would certainly have been tattooed on his left arm, as he states himself, material to the guilt or innocence of Eric Hunt in light of the charges that had been brought against him? Certainly, Eric Hunt, not long out of college at the time and who had been assigned to read Night in school, had come to doubt the truth of Wiesel’s assertions and descriptions in the book, and believed that if he could confront Wiesel alone, unguarded, he could convince him to tell the truth.

Does the suspicion that Wiesel necessarily lied in his book Night about what he saw and experienced at Auschwitz-Birkenau because he lied about the existence of a tattoo which he has always claimed as proof of his credentials as an Auschwitz survivor, exonerate Eric Hunt from some of the charges brought against him by the State of California? Is it material to the case? Perhaps not, but it does show cause for Eric Hunt’s desire to speak to Elie Wiesel in an unguarded moment, which was what he was attempting to do.

[I have changed my mind about this materiality issue. Whether Wiesel has a tattoo or doesn’t is very “material” to whether his “protected status” as a holocaust survivior gives him the right to avoid questions by the public, such as Eric Hunt was seeking to ask. Wiesel admits he was not harmed in any way by Hunt, but only frightened for a moment — this hardly warrants a charge of kidnapping against Hunt, or for Hunt to be found guilty of “assault”, and even more, of being guilty of a “hate crime,” which is a felony. Without the “hate crime” attachment, Hunt would not now be burdened with the legal status of felon.

If Elie Wiesel is lying about having a tattoo from Auschwitz on his arm, it is Elie Wiesel who is guilty of spreading hate (against Germans collectively, and yes, against Eric Hunt), and has been doing so since 1960 when his book Night was first published. Eric Hunt was therefore trying to stop the hate by trying to get the truth out of Elie Wiesel.]

If Elie Wiesel cannot be legally found guilty of perjury because of questions of materiality, he will certainly be guilty of perjury in the eyes of the public if he does not produce the famous tattoo A-7713 on his arm—the sooner the better. We are waiting, Mr. Wiesel.

Watch a new, short video on the subject.

Addendum:

”Auschwitz survivor Sam Rosenzweig displays his identification tattoo.” From Wikipedia According to the information below, this man was in the “regular” series—numbers not preceeded with a letter of the alphabet. Note also that the tattoo is on the outside of the left forearm.

This is the best looking tattoo I could find on the Internet. If you want to have your faith in the Auschwitz Holocaust story badly shaken, google “Auschwitz tattoos” (or any variation thereof) – Images, and see what comes up. Frightening! Of the little that is there, most look like the numbers are way too big, and you find the same few people exhibiting their specimen.

[It should be noted that Auschwitz-Birkenau was the ONLY camp that tattooed its inmates. It was a decision by the camp authorities, not by the SS hierarchy or Adolf Hitler. It probaby came about because of the large number of inmates at Auschwitz-Birkenau-Monowitz and their tendency to give false names and trade places with one another.]

However … George Rosenthal, Trenton, NJ, an Auschwitz Survivor, has written an “authoritative” account at Jewish Virtual Library based on “documents” obtained from The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. (Sorry, no pictures here either, or on the USHMM website. Elie Wiesel was a major driving force in the creationof the USHMM; why didn’t he volunteer his tattoo to be pictured on their website as an example of what a genuine tattoo looks like? Why does the USHMM have no images of a tattoo?)

Mr. Rosenthal writes:

The sequence according to which serial numbers were issued evolved over time. The numbering scheme was divided into “regular,” AU, Z, EH, A, and B series’. The “regular” series consisted of a consecutive numerical series that was used, in the early phase of the Auschwitz concentration camp, to identify Poles, Jews, and most other prisoners (all male). This series was used from May 1940-January 1945, although the population that it identified evolved over time. Following the introduction of other categories of prisoners into the camp, the numbering scheme became more complex. The “AU” series denoted Soviet prisoners of war, while the “Z” series (with the “Z” standing for the German word for Gypsy, Zigeuner) designated the Romany. These identifying letters preceded the tattooed serial numbers after they were instituted. “EH” designated prisoners that had been sent for “reeducation” (Erziehungshäftlinge).

In May 1944, numbers in the “A” series and the “B” series were first issued to Jewish prisoners, beginning with the men on May 13th and the women on May 16th. The “A” series was to be completed with 20,000; however an error led to the women being numbered to 25,378 before the “B” series was begun. The intention was to work through the entire alphabet with 20,000 numbers being issued in each letter series. In each series, men and women had their own separate numerical series, ostensibly beginning with number 1.

According to this, since there was never a “C” series, the maximum number of prisoners that could have been tattooed after May 1944 was 45,378.

Under “Notes” at the bottom of the page, four books are listed, all by holocaust historians. Are these the “documents” referred to? It also says Source: Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies at the very bottom of the page, as if referring to the entire page. This Center is located at the University of Minnesota. The affiliated faculty reveals mostly Jewish names.

I report all this because I’m looking for authoritative sources for the exact placement of the tattoos on the left arm, but one doesn’t find that answer even at the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial Museum. Why all the uncertainty? Could it be because so many pseudo-survivors have tattooed themselves in unusual ways and places, and the authorities don’t want to nullify their legitimacy?

19 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: Auschwitz tattoos, Elie Wiesel, Eric Hunt, George Rosenthal, perjury,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Monday, April 4th, 2011

By Carolyn Yeager

Cliches are all Chapman students get from the Master of Platitudes’much-ballyhooed visit. Above: Elie Wiesel looks frail in this group photo taken after he spoke to students at the Sala and Aron Samueli Holocaust Memorial Library at Chapman University. (Photo credit: Orange Country Register)

Above: Elie Wiesel looks frail in this group photo taken after he spoke to students at the Sala and Aron Samueli Holocaust Memorial Library at Chapman University. (Photo credit: Orange Country Register)

The Los Angeles Times sent its own reporter to cover the Holocaust Hero’s grand arrival at Chapman University during the first week of April. The Local section of the newspaper had a report on Wiesel’s visit with 21 students in the specialized Holocaust Library on the campus.

Wiesel has fewer answers these days (not much is expected of him) and speaks in a sort of cliché-language that he has mastered. He can be confident his listeners will supply a profound meaning to any utterance that comes forth from his mouth. For example:

One (student) wanted to know how Wiesel managed to overcome the memories of the deaths of his father, mother and sister to write his first book, “Night,” an autobiographical account of … Nazi concentration camps.

With deep sadness in his eyes, Wiesel replied, “Only those who were there know what it was like. We must bear witness. Silence is not an option.”

Wiesel did not really like this question and gave a short answer that was not an answer at all. The question was: How did he overcome the [painful] memories in order to write his book? His actual answer, interpreted, was: “I won’t, or I can’t, answer your question.” We can ask why he won’t answer that question, and also why he has not ever answered that question. Could it be because he has no idea how to answer it since such a thing did not actually happen to him?

To make it sound like he’s giving some kind of answer, he adds two things that have nothing to do with the question: “We must bear witness” and “Silence is not an option.” These are both favorite sayings typically associated with him. Upon hearing him say them, his listeners are satisfied that they are hearing the real Wiesel, that they are blessed by a “transforming” moment.

Another question was more to Wiesel’s liking. “How can this generation preserve what you learned there?”

Wiesel brightened as he said, “Listen to the survivors. They are an endangered species now. This is the last chance you have to listen to them. I believe with all my heart that whoever listens to a witness becomes a witness. Once we have heard, we must not stand idly by. Indifference to evil makes evil stronger.”

More platitudes. But a reader brought to my attention that Wiesel is contradicting something he said on another occasion. Even though we know contradictions are the usual fare from this man, it’s of note that in a 1978 interview with the New York Times, Wiesel pronounced:

“The Holocaust [is] the ultimate event, the ultimate mystery, never to be comprehended or transmitted. Only those who were there know what it was; the others will never know.”*

This fits his first answer, but not his second. So, is it that “only those who were there know what it was like” (meaning it’s impossible to transmit to others), or is it that we can all “become a witness” (and speak with authority about what it was like)?

If you really want the truthful answer, dear readers, it is whatever benefits the Holocaust Industry. That is the whole reason Elie Wiesel goes to Chapman University—to create publicity for Holocaustianity—since he adds no real value to the students’ learning. Still, it’s all taken very solemnly by the faculty, the mainstream media, and the impoverished students themselves, who don’t realize how they’re being cheated. In a university setting, they are expected to swallow whole whatever they hear from iconic sources re the holocaust. The real questions they have are not answered. It is a farce of education. This Presidential Fellowship shows us once again, when it comes to Elie Wiesel it is always “much ado about nothing.”