Posts Tagged ‘Buchenwald’

Sunday, October 16th, 2011

By Carolyn Yeager

Elie Wiesel’s father Shlomo in 1942, according to Hilda Wiesel.

Is he 39 or 48 years old?

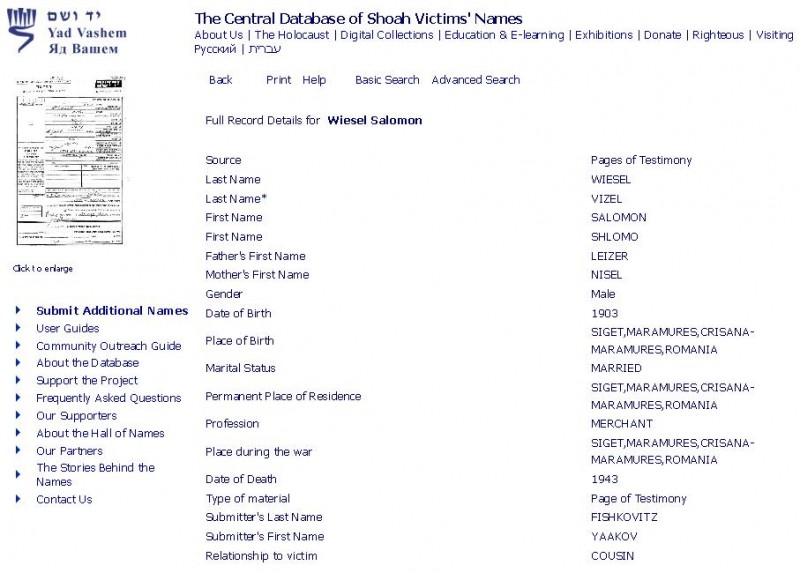

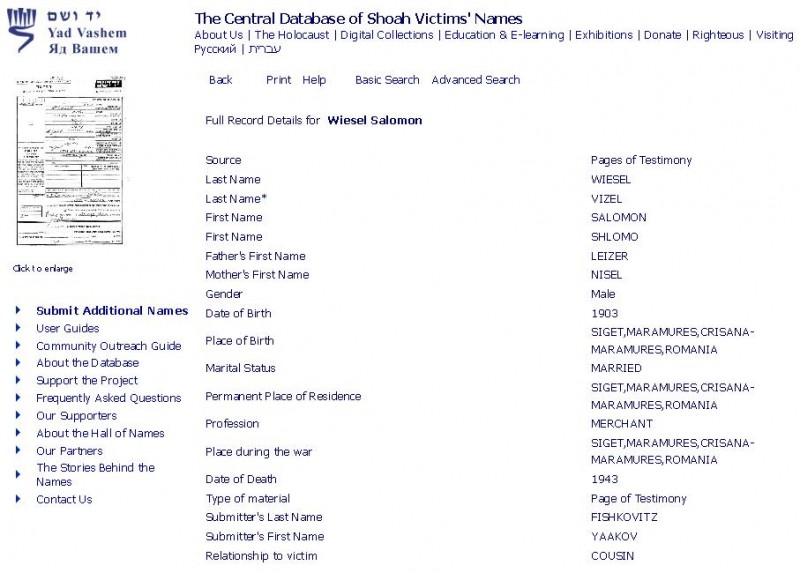

A report in the Yad Vashem Shoah Victims database by Yaakov Fishkovitz contradicts Elie Wiesel’s story about his father’s death.

Yaakov (Jacob) Fishkowitz filled out a death form in 1957 for his cousin Shlomo Wiesel, shortly after Yad Vashem first began its “Central Database of Shoah Victims Names.”1 He also filled out a form for Shlomo’s mother Nisel Basch Wiesel, his aunt. The cousins shared a maternal grandfather, Moshe Basch.

Yaakov was the son of Mentza Basch, daughter of Moshe, and Fishel Fishkovitz. Yaakov recorded Shlomo’s date of birth as 1903, which is much later than has been assumed, making Elie Wiesel’s father only 40 years old when he died! However, since Wiesel himself was 14 or 15 years old in 1943 this makes a lot more sense for an Orthodox Hasidic father-son. I will examine this further on in this article.

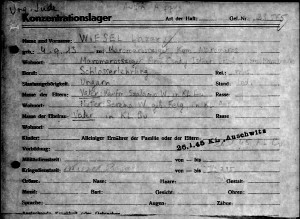

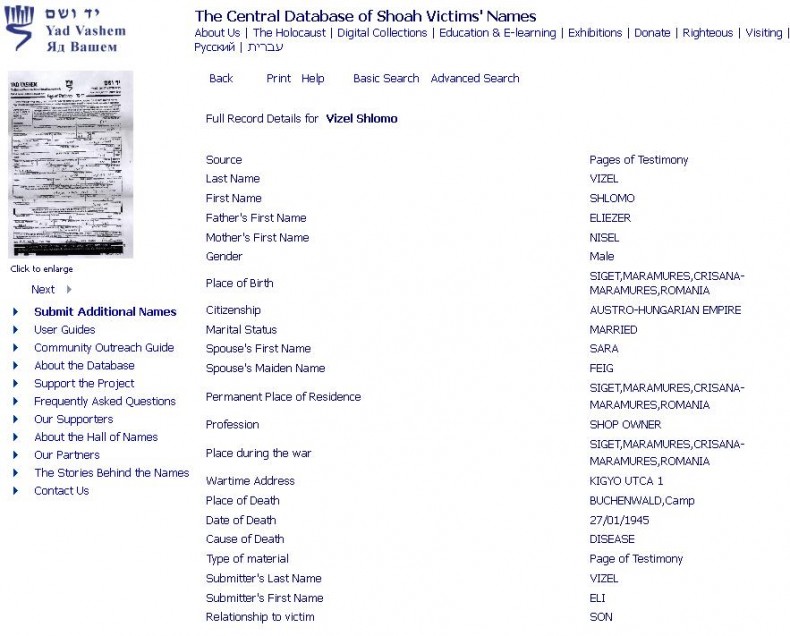

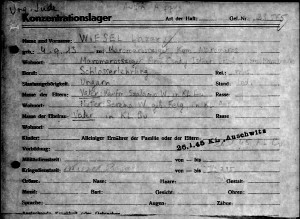

As seen in the two Yad Vashem Shoah Victim reports below—one by Fishkovitz and the other by Elie Wiesel—Yaakov spells the last name as both Wiesel (German) and Vizel (Roumanian). The German ‘W’ is pronounced as the English ‘V;’ similarly with s and z. He also gives both the formal name Salomon and its casual form Shlomo. Elie, on the other hand, spells his father’s name as Vizel and his own name as Eli Vizel, dropping the ‘e’ in his first name that he adopted for his post-war identity.

Shlomo’s children have never or seldom used the formal ‘Salomon’ for their father, but they do agree that Eleizer (or Leizer) and Nisel were his parents and that he was born in Sighet; that he was married and operated a store. Yaakov uses the word “merchant” while Elie uses “shop owner.” Elie adds his mother’s name, Sara Feig, but leaves his father’s date of birth blank, while also giving an incorrect date for his death according to his own book, Night.

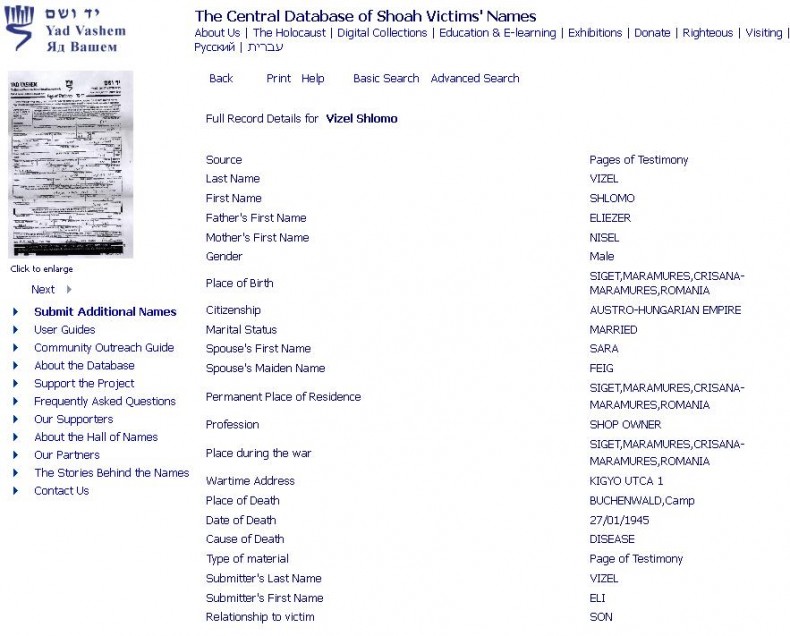

The details from the forms (the form itself is shown in upper left corner), are translated into English from the Yiddish that was used by Elie and partially by Yaakov to fill out the forms. However, the dates can be read. The first one is by cousin Fishkovitz in 1957; the second one by son Elie in 2004, almost 50 years later.

(Click on forms to see a larger, full image.) Notice that each submitter fills in what he knows or believes to be important. Yaakov knew the year of his cousin’s birth; it may have been close to his own. Elie did not know, or doesn’t want us to know. He has never written it or given that information to an interviewer. This is important, but even more important is that Yaakov says Shlomo died in 1943 in Sighet*, the year before the deportation of the Jews of Sighet! This changes the entire narrative. [*Correction was made in a later article: it actually says Shlomo lived in Sighet during the war; he died in a labor camp in 1943.]

What evidence do we have for Shlomo’s age?

In Elie Wiesel’s Night (“a true story, every word is true”) Eliezer’s father answers “fifty” when asked his age by a friendly Jew when they first arrive at Auschwitz in May 1944. Eliezer answers that he is fifteen years old. The Jew tells them to lower and raise their ages respectively, which they do. (Even so, they’re put in a line that takes them right up to the edge of a pit of fire before they are turned away.) Because of this, Shlomo Wiesel has generally been assumed to have been born in 1894, although that has never been verified. For example, Wikipedia does not give a date.

In Hilda Wiesel’s Shoah Foundation testimony, she shows the photo of her father that is at the top of this article, and says it was taken in 1942. Does he look like he is 39 in this photo (born in 1903) or does he look to be 48 (because he was 50 in 1944)? It’s impossible to tell for sure, but he looks like a youngish man to me.

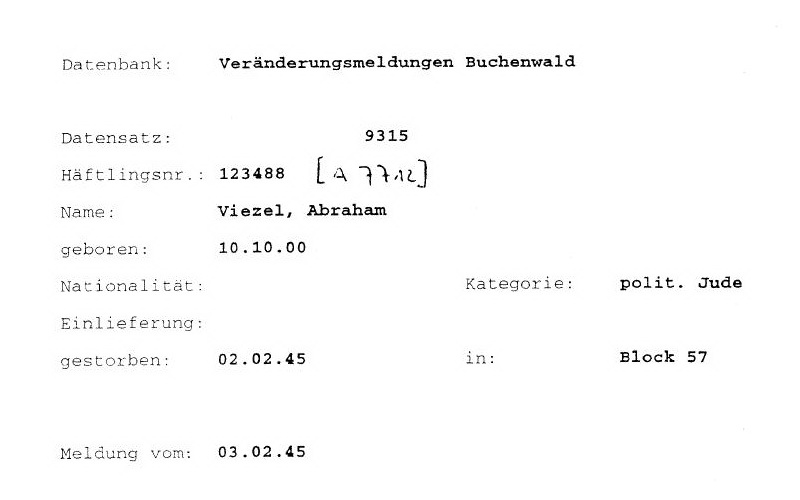

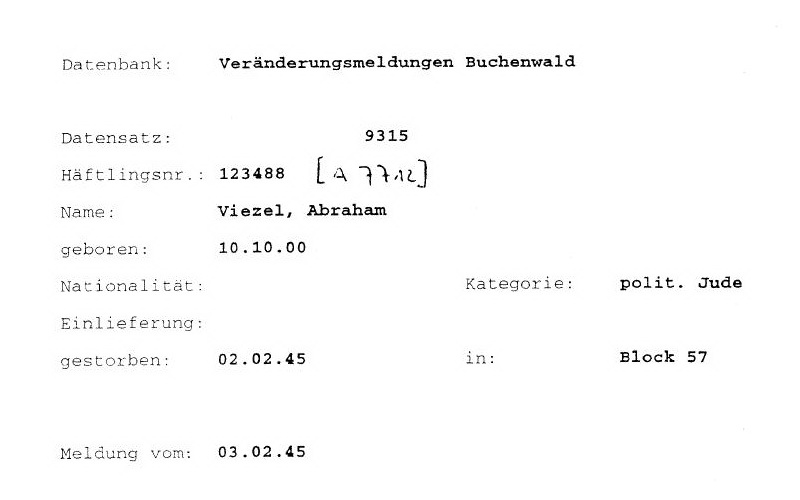

As we know, there are no records at Auschwitz-Birkenau or Buchenwald for a Shlomo Wiesel that fits his profile. Nor are there any for Elie Wiesel and his profile. The records that are used by the “Wiesel-in-Buchenwald” supporters are those for Abraham Viezel (also spelled Vizel or Wiesel), born Oct. 10, 1900 in Sighet, who died at Buchenwald on Feb 2, 1945. He died in Block 57; the death report was made out on Feb. 3, the following day. Yet Elie Wiesel claims in Night and elsewhere his father died on Jan. 28 and was carted off to the cremation ovens immediately, fully 5 days before Abraham’s death took place.

Death record for Abraham Viesel at Buchenwald, brother of Lazar Wiesel whose Auschwitz # was A7713

This Abraham Viesel is the same Abram Wiesel who was the older brother of Lazar Wiesel, according to Myklos Gruener, who says the two brothers had become his comrades at Auschwitz-Birkenau after the death of his father. (Auschwitz records exist for Myklos, his father and two brothers, as well as for Lazar and Abram Wiesel, including each of their numbers.) Abram’s Auschwitz tattoo number A7712 is written by hand on this death record, as well as his Buchenwald number, 123488.

If Shlomo died in 1943, this would explain why there is no death record for him at Buchenwald. Are there any other convincing reasons to go along with the 1943 date? Yes. In Night and in All Rivers Run to the Sea, we’re told of Shlomo’s resistance work helping Jews with legal problems and those who needed to flee from one place to another. He had been jailed for it, something mentioned by both Elie and Hilda. Elie characterized his father’s tireless efforts as “out of a loving, helpful heart.” But was his father, and his family, more radical than we’ve been led to believe? Was Shlomo’s life a dangerous one? Were there disputes about money—money collected to buy weapons, or for passage to safe places? Or perhaps there was anger within the Jewish community over who was being helped and who wasn’t?

In All Rivers, on page 4, Wiesel writes that as a child and adolescent he “saw his father rarely […] The Sabbath was the only day I spent with him.” “Often preoccupied,” his father spent the week in his little grocery store and at the “community offices where he worked to assist prisoners and refugees threatened with expulsion.” Expulsion from where? By whom? What were the community offices? Wiesel names Sighet as a “sanctuary for Jews fleeing …since 1640.”

What knowledge can we piece together about Shlomo?

Shlomo was a preoccupied man. He ran a store. He took in deliveries. He may have been involved in smuggling – guns, people, documents. Smuggling was a way of life among the Zionists. Jews began going to Palestine long before Elie Wiesel was born. There were different factions of Jews—the Haganah was formed in 1920 to guard Jewish settlers in Palestine. In 1931 the Irgun splintered off and there was sometimes bitter enmity between the two organizations all the way up to 1948. The Irgun policy was that every Jew had a right to enter Palestine and it became the major smuggling arm for the Zionists. The Irgun worked in Poland, for example, in the 30’s to bring Jews into Palestine with the cooperation of secret agencies of the Polish government. (See “The Role of the Irgun in Central and Eastern Europe” at http://www.eliewieseltattoo.com/elie-wiesel-and-the-mossad-part-ii)

It is fully possible that as things heated up in 1943, Shlomo got caught in some crossfire — perhaps was killed by the Hungarian police. If this were the case, Elie, as only son, may have been sent to France for safety before the deportations of Spring 1944. Further, if this were the case (a story as good as any other), Elie was an Irgun-supporting Zionist from an early age, which fits everything we know about him.

On page 8 of Night, Wiesel wrote:

In those days [Spring 1944] it was still possible to buy emigration certificates to Palestine. I had asked my father to sell everything, to liquidate everthing, and to leave. ‘I am too old, my son,’ he answered. ‘Too old to start a new life. Too old to start from scratch in some distant land …’

If he were only 40, that is not credible. Even at 50 he was not too old, unless he really didn’t believe the worst would happen and that things would right themselves. His children were certainly not too old and he would have them to look after him in his old age. Something doesn’t add up here. This “good man” doesn’t protect his family because he feels too tired at age 40-50 to go somewhere new? He allows them all to be taken prisoner because he can’t see what’s coming, even though he’s spent his adult life helping Jewish prisoners and refugees? Wiesel often fails to give convincing explanations for why events happen as they do in his writings. I have noticed it again and again, and commented on it. It seems to me to be a combination of laziness and lack of true inventiveness. He has admitted that he was rather spoiled and lazy in his childhood and youth; one doesn’t see any evidence of change.

The age of the typical Hasidic bride and groom

Back to the question of the appropriateness of Sholmo Wiesel being age 40 in 1943-44. The Hasidic sect sees the ideal age of marriage for a male as 18-21. They encourage the bride and groom to be close in age. Taken from the New York Times article on an important Hasidic wedding:

What they saw was a marital merger of two leading international Hasidic dynasties, the Bobovers of the Borough Park neighborhood in Brooklyn and the Satmars of Williamsburg. The 19-year-old groom is a grandson of the Bobover Grand Rabbi, Shlomo Halberstam. The 18-year-old bride is a granddaughter of the Satmar Grand Rabbi, Moses Teitelbaum. The two grand rabbis are the descendants of the first Hasidic leaders in Europe. They are also first cousins and close friends.2

Another Hasidic wedding is announced, this one in Israel.

Even longtime Hassidim are raising their eyebrows: A 16-year-old young man is engaged to his 15-year-old second cousin, both great grandchildren from “Hassidei Vizhnitz.” Thousands of members of the Vizhnitz Hassidic sect, one of the largest and wealthiest in the world, are expected to attend the festive wedding ceremony, which will take place in approximately another year.3

If Shlomo were born in 1903, as Yaakov Fishkowitz has it, he would have been 25 years old in September 1928 when his third child and first son Eliezer was born. His first child Hilda was born in August 1922, when he would have been 19 years old. Perfect for a Hasidic man!

On the other hand, if he were born in 1894, he was already 34 when Elie was born, and 28 when he had his first child. That is too old and is not in the tradition of his community! That may be why Wiesel avoids mentioning his father’s date of birth; it does not fit the story of Night, which he adopted as his own. Here’s a thought: Is there an Hasidic law or tradition that forbids lying about one’s parents and other ancestors? Probably, which can be the reason he says so little about his father, mother and grandparents as far as checkable data goes.

Is it not strange for the ‘High Priest of Memory’ to be so negligent in recording the history of his family? He only filled out the Yad Vashem form (with a camera aimed at him) at the behest of that institution, as an encouragement to others to do the same. That was admitted in the TV publicity given it. Plus it is the only Shoah victim form he filled out. His mother and sister are not in the Yad Vashem Shoah Victim database! He says it’s because he’s written about them in books, so the bare facts on a form are not necessary. But in his books, he doesn’t give dates or checkable details. Why has no family member recognized the death at Auschwitz of Sara Feig Wiesel and her daughter Tzipora by filling out a form?

Is Elie Wiesel’s story about his family and their fate entirely or just partially false?

We know Wiesel’s story about his family and youth to be full of falsehoods. His book Night has been lampooned as much as it has been praised because of the contradictions and inappropriate descriptions of people and events it contains. He has long been described as a fabricator, an exaggerator, a false witness. However, here at Elie Wiesel Cons the World our mission is to expose every lie, not just the most obvious of them. So we dig deeper.

Elie Wiesel has every reason to want his father with him at Buchenwald since the story in Night, which started out as fiction, is about a son and his father. The story also says his mother and younger sister perished on their first night in Birkenau. But if Shlomo died in 1943 and never went to Auschwitz, did any of his immediate family go? Remember, there are no records for any of them there.

Could Elie Wiesel have known in 1955 how huge the Holocaust Industry would become? No, no one did. Would Elie Wiesel in 1958 have anticipated the intense scrutiny of this book Night, or his own star status in which he himself would come under intense scrutiny? No, again. Elie Wiesel didn’t prepare for the kind of future he turned out to have, so he’s been “playing it by ear” ever since—and using his untouchable Jewish holocaust survivor status with which to protect himself. His sisters and other family members and friends were silenced to keep the ‘wrong’ information from slipping out. Journalists were obviously ordered to stay away from them!

But, perhaps unbeknownst to their inner circle, there lay two victim reports with vital information relating to Elie Wiesel in the Yad Vashem databank filled out in 1957 by Yaakov Fishkovitz, one of which is displayed in this article. The other is for his aunt—Shlomo’s mother—Nisel Basch Wiesel, stating she was born in 1881 and died in 1944 at Auschwitz (in her 63rd year). Another form for Nisel was filled out in 1999 by her grandson, Eliezer Shlomovitz, living in Los Angeles CA. He gives her date of birth as 1880 with a question mark. I will write about Nisel Wiesel in a separate article, but for now I want to establish that if Nisel were born in 1880-81 she would have been only 13 years old when she gave birth to her son Shlomo, if he were born in 1894. Since Shlomo was not her first child, but perhaps even her fifth or sixth (undetermined as of now), this is clearly impossible. If Shlomo were born in 1903, it is doable.

Thus, we have every reason to doubt everything about Elie Wiesel’s story of his family history and their concentration camp credentials. I will continue with this fascinating and very important examination of the Wiesel extended family in an upcoming article. Stay tuned.

Endnotes:

1. Yad Vashem was established in 1953 as the official “remembrance authority” (for the Jewish Shoah) by the Knesset, Israel’s parliament. At that time, Jews were told that all Jews who died at the hands of the Nazis or their accomplices during the years of Nazi power, i.e. 1933-1945 could be considered Shoah victims. This includes Jewish soldiers serving in the Soviet and Polish armies, who were taken prisoner and died in Nazi POW camps. Jews who survived until the liberation but died within six months of liberation are also considered Shoah victims.

Another category is ‘Shoah survivor’ All those living in Nazi-occupied territories from 1933 onward could be considered victims of the Nazis, including French, Bulgarian and Romanian Jews, and even those who went deep into the Soviet Union. Also included are “Jews who forcefully left (?) Germany in the 1930s.” Even those who went to Israel, obviously No other group has so generously allocated ‘victim-opportunities’ to its people. This is called Chutzpah in Yiddish. (Information taken from http://www.yadvashem.org/wps/portal/!ut/p/_s.7_0_A/7_0_S5?New_WCM_Context=http://namescm.yadvashem.org/wps/wcm/connect/Yad+Vashem/Hall+Of+Names/Left+Links/en/3HON_FAQs)

2. http://www.nytimes.com/1998/09/04/nyregion/a-royal-wedding-a-family-affair-two-hasidic-dynasties-unite-in-brooklyn-gala.html?pagewanted=all&src=pm Further of interest: The Satmars originated in Hungary and the Bobovers came from Poland. […] Because Hasidic families often have 10 or more children, the two groups now have tens of thousands of followers in Brooklyn and more around the world.

3. http://www.israelnationalnews.com/News/News.aspx/133130 “We have a tradition of marrying at a young age, but we usually mean 19-22, although there have been occasions of marriages before the age of 18,” one Vizhnitz member told the Hebrew-language daily Yisrael HaYom. “However, marrying at the age of 15 is definitely exceptional.”

Please read this article next: New Information – Shlomo Wiesel dies in labor camp in 1943?

14 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: Abraham Viesel, Buchenwald, Elie Wiesel, Hasidic marriage, Hilda Wiesel, Night, Shlomo Wiesel, Yaakov Fishkovitz, Yad Vashem Shoah Victims Database,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Friday, September 23rd, 2011

By Carolyn Yeager

The real inmate at Buchenwald, Lazar Wiesel, 31 years old in 1944, was the son of Szalamo and Serena Feig Wiesel of Sighet.

We present the question of why the personal information on Lazar Wiesel is so close, but still far from exact, to that of Elie Wiesel. Can we believe, as Prof. Kenneth Waltzer would have it, that these were errors in taking down the information on Elie, and Lazar is really Elie? No, we can’t because the nature of the differences cannot be simple errors. Lazar had a brother Abram with him in the camps; the 44 year-old Abram (in 1944) cannot be turned into Elie’s father. And he certainly can’t be turned into Lazar’s father as only 13 years separated them. But it is very possible that the two families were related and that a part of Elie’s immediate family escaped the deportation altogether. Many so-called Hungarian Jews did – many more than are officially acknowledged. Keeping this in mind, I will examine the family names and see what they tell us.

Lazar Wiesel’s Buchenwald File Card (below) records Lazar’s father, Szalamo (equates to Sholomo), as being interned at Buchenwald.1 But more striking, Lazar’s mother, Serena Wiesel nee Feig, is listed on this card as being interned at KL Auschwitz. (As we know, Elie’s story is that upon arrival he saw his mother and sister moving away with the women and never saw them again. The idea they went to a gas chamber is pure speculation copied from other books.)

CLICK ON CARD FOR AN ENLARGED VIEW. Buchenwald Registration file card for Lazar Wiesel, birth date Sept, 4, 1913, arriving on Jan. 26, 1945 from KL Auschwitz.

Elie Wiesel’s parents are known to be Shlomo and Sara (or Sura) Wiesel, nee Feig.

In Jewish Orthodoxy (the Wiesel’s were members of the Hasidim sect) and in Eastern Europe generally, certain family names were repeatedly used—recycled if you will. This is certainly the case in the Wiesel family with the names Eliezer, Elisha, Shlomo and Sara, and probably some others we don’t know about.

It’s no surprise that we find the name of the founder of Hasidic Judaism to be Rabbi Yisroel ben Eliezer, and that he was born to Eliezer and Sara in Okopy, a small village that over the centuries has been part of Poland, Russia, and now Ukraine.

Wiesel was named after his grandfather Eliezer. His other grandfather on the maternal side is Dovid Feig.

Looking for genealogical information on Elie Wiesel is a disappointing affair—so little can be found. For such a famous person, a Nobel Peace Prize Laureate, to have his family history wiped away, hidden or not known is strange indeed. How to explain it when Hasidic family ancestry is traditionally honored and held in high esteem. It must be purposely hidden. The Jews talk about Adolf Hitler hiding his ancestry. Not at all. Hitler’s complete and accurate genealogy is available on the Internet, but Wiesel’s is not. How do we figure that?

The #1 site on Google Search for Wiesel’s genealogy is Geni which has only very limited information. There is nothing additional to be found on Wikipedia. I have filled in the gaps with two pages of testimony from Yad Vashem’s online database—one for his father that Wiesel filled out himself, and one for his father’s mother, Nisel, that was filled out by her grandson Eliezer Shlomovitz, who lives in Los Angeles, CA. This is all I could uncover and I do not guarantee the correctness of any of it.

Father: Shlomo Elisha Wiesel

- Parents: Eliezer Vizel and Nisel Vizel nee Bash. This grandfather Eliezer died serving on the side of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in WWI.

- Nisel was born in Chust (or Hust, not far from Sighet), later Ruthenian-Czechoslovakia , in 1880 to Moshe and Yehudit Bash, according to a Yad Vashem death report (mentioned above).

- Shlomo is said by several sources to have been born in 1894, but I think this is deduced from the book “Night” where he is said to have been age 50 in 1944. If this were correct, it would make Shlomo’s mother’s age 14 when he was born — highly unlikely. Elie Wiesel never gives his father’s or mother’s birth dates though it’s not like he doesn’t know.

- Wiesel writes in his memoir All Rivers Run to the Sea that he met his father’s brother Samuel in New York, but he has never written about his cousin Eliezer Shlomovitz in Los Angeles.

Mother: Sara Feig Wiesel

- Parents: Dodye (Dovid) Feig; no mother given

- Wiesel highly praises this grandfather in All Rivers and writes, “… in 1944 my parents invited him and his wife to live with us.” His wife, not ‘my grandmother.’ That is the only mention of ‘her.’ Seems clear she was not Elie’s grandmother, but a new wife. In any case, grandfather Feig declined and went to stay with his sons.

- Elie writes in All Rivers: “I had four uncles on my mother’s side: Chaim-Mordechai, Ezra, Israel and Moshe-Itzik

- He met an ‘Uncle’ Morris in New York.

From the little we have available, we can see certain names repeating. Elie Wiesel gave his son his father’s name, Shlomo Elisha. He himself was named after his paternal grandfather Eliezer. A cousin, another grandson of his paternal grandmother, is also named Eliezer. This cousin’s last name is Shlomovitz. From this we can begin to ascertain that Eliezer, Shlomo, Elisha and Sara are “family names” within the extended Wiesel family, along with being Hasidic names.

Two marriages between the Wiesel’s and the Feig’s

Looking back at the Lazar (from Eliezer) Wiesel who was at Buchenwald, we see another marriage between the Wiesel’s and the Feig’s. We see the same names: father is Szalamo (Shlomo); mother is Serena Feig. Lazar is 15 years older than Elie and his brother Abram is 28 years older, and they are from the same city, Sighet. It seems pretty clear to me that these are two branches of the family tree.

Matchmaker, Matchmaker, make me a match!

Orthodox men and women usually meet through matchmakers in a process called a shidduch. A matchmaker’s services are necessary because of the constant intermarriage going on within the closely knit Orthodox communities. A matchmaker (shadchan) knew of the relations between those in the community, or could find them out, and could therefore prevent or warn against marriages between a couple who were too genetically similar. This role is not mentioned on Wikipedia and other Jewish sites, but it’s the most important one. In Night, Wiesel wrote that in 1943 his mother “was beginning to think it was high time to find an appropriate match for Hilda” who was already 21 years of age.2

Orthodox men and women usually meet through matchmakers in a process called a shidduch. A matchmaker’s services are necessary because of the constant intermarriage going on within the closely knit Orthodox communities. A matchmaker (shadchan) knew of the relations between those in the community, or could find them out, and could therefore prevent or warn against marriages between a couple who were too genetically similar. This role is not mentioned on Wikipedia and other Jewish sites, but it’s the most important one. In Night, Wiesel wrote that in 1943 his mother “was beginning to think it was high time to find an appropriate match for Hilda” who was already 21 years of age.2

The two families, Feig and Wiesel, may have been recognized as having diverse enough genetic relationship to one another to make for viable marriages. Perhaps there was a history of successful unions between the two family lines. In any case, it can explain the similarity in personal information between the older and younger Wiesel, and also the temptation to claim the one to be the other. The family members can be trusted to remain silent about it.

This last part is speculation, but one thing we notice is that Elie Wiesel does not want us to know who or where are the members of his family, and even more, he doesn’t want any of his family members to talk to us, the general public. We are not to know anything but the simplistic legend that he and his supporters and defenders have created for our consumption.

An interesting side-note: I just discovered a book From Generation to Generation by Arthur Kurzweil, published in 2004, which features on the cover “Foreword by Elie Wiesel.” This foreword turns out to be only one page long, much shorter than the Acknowledgements even, and consists of a few vague words about the mystical aspect of names. What is interesting is that the book is 400 pages of “how to research your Jewish genealogy.” If Wiesel has researched his own, he certainly is not publishing it. Wiesel gives himself the prerogative of remaining a very private man, while working hard to become a highly public name. Jewish chutzpah at work.~

Endnotes:

1. Myklos Gruener never mentioned a father for Lazar and Abram, only his own father.

2. Elie Wiesel, Night, Hill and Wang, 2006 (original copyright 1958), p. 8

1 Comment

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: Abram Wiesel, Buchenwald, Elie Wiesel, Lazar Wiesel, matchmakers, Sara and Serena Wiesel nee Feig, Shlomo Wiesel,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Monday, July 18th, 2011

By Carolyn Yeager

Ken Waltzer wrote in his comment on this blog on June 27th:

“More important, Elie Wiesel’s commentary in Night bears fairly close resemblance to the actual experiences he had at Buchenwald—as recorded in camp documents.” (my italics)

What are we to make of the words “fairly close resemblance?” According to Waltzer—and to Wiesel—Wiesel is writing down his own experience. “Every word is true!” Wiesel has said of his book Night. Thus it should exactly resemble the actual experience he had. I’m going to examine closely what is written in Night about Buchenwald to see if that is the case.

It’s not too difficult because the newest English edition of Night1—a new translation by wife Marion Wiesel which changes (corrects) some of the more blatant “boo-boos” found in the original 1960 edition—comprises only 115 pages. Of that, Wiesel’s description of his time at Buchenwald begins on page 104, giving it only 11 pages (one page being blank).

Wiesel wrote a new preface for this new translation in which he tries to answer some of the more common criticisms of his book. His answer to the differences between the Yiddish And the World Remained Silent and Night is that he cut passages he thought might be superfluous … or “too personal, too private, perhaps.” Strange thing to say since he had already published it. Concerning Buchenwald, he quotes the original writing about the death of his father, where the club-wielder is called “an SS” three times! In Night, as you will see below, this person becomes simply “an officer.” Naturally I ask: Did this scene even happen? Wiesel also tries to explain why he cut out from the ending so much of what was in the Yiddish version, but in doing so he leaves unmentioned an extensive part of what he cut. I have quoted these two endings in Shadowy Origins of Night, Part II.

Wiesel begins his experience at Buchenwald by writing that upon reaching the entrance to the Buchenwald camp along with his father and all the new arrivals from his transport, the SS counted them and they were directed to the Appelplatz (roll call area inside the camp) where loudspeakers ordered “Form ranks of fives! Groups of one hundred! Five steps forward!” He then writes, “A veteran of Buchenwald (as he puts it), told us that we would be taking a shower and afterward be sent to different blocks.” He makes it sound as if it were one of those among them, but it actually had to be a Kapo.

He writes that hundreds of prisoners crowded the shower area and made it difficult to get in, therefore his father wanted to find a place to sit down and wait—which he did in a pile of snow where there were other ‘bodies’ sticking out. Dead or alive we’re not told. It’s one of those literary scenes wherein Eliezer confronts Death via his fear of his father’s death. He writes: “This discussion (with his father) continued for some time.” Then … “sirens began to wail … lights went out … guards chased us toward the blocks.” They obviously did not get a hot shower. Wiesel adds: “The cauldrons at the entrance found no takers.” 2

Are we to believe that the kapos, or “veterans of Buchenwald,” allowed non-disinfected, non-showered new arrivals into the barracks, possibly carrying lice and other vermin with them? No way could this have happened. Yet Wiesel writes: “We let ourselves sink into the floor. To sleep was all that mattered.” I guess it was okay because they didn’t get into the beds.

In the morning, having lost track of his father the night before, he went to search for him. What about the regimentation? What about the early morning roll call? Wiesel writes: “I walked for hours without finding him. Then I came to a block where they were distributing black ‘coffee.’ ” 3 He heard his father’s voice asking for some coffee. He brought it to him. “He was lying on the boards,” meaning, I suppose, a bare bunk. Then, “We had been ordered to go outside to allow for cleaning of the blocks (barracks). Only the sick could remain inside. (If that was the case, they were not fumigating.) We stayed outside for five hours. We were given soup. When they allowed us to return to the blocks, I rushed toward my father” … who told Eliezer he had not been given any soup because “they said we would die soon and it would be a waste of food.”

Apparently, he stayed with his father in that barracks, making sure he was fed. Were they allowed to live in whatever barracks they chose? Again, there is no explanation given for this. He then writes that on the third day after their arrival everybody had to go to the showers, even the sick. Having done that (with no description of the process at all), they again had to wait “a long time” outside the barracks while they were being cleaned.

He fills a couple of pages with scenes of watching his father deteriorate amidst all the heartlessness. Then, after a week, a Blockälteste (block warden) told him he couldn’t save his father and he should help himself by eating his father’s rations. Instead, he pretends to be sick so he can stay in the barracks with his father. He doesn’t go to roll call. Now comes the famous passage in which he writes: “In front of the block, the SS were giving orders. An officer passed between the bunks. My father was pleading: “My son, water…I’m burning up…My insides …” The officer shouts at him to be quiet, walks over with a club and hits him “a violent blow to the head.” On that night, January 28, 1945, his father allegedly died.

The main problems with reality in this passage are:

1) The SS is known to have not been active inside the camp; the prisoner-trustees, usually communists, took care of giving the prisoners their orders. So the SS would not be in front of the block giving orders.

2) “An officer” can only be an SS officer. But they never came inside the barracks. Inmates, no matter how much “in charge” they might be, were not called officers. So who was this mysterious “officer” who was inside the barracks? Not SS at all; just part of the fiction and another attempt to assign brutalities to the SS.

Eliezer says he did not weep for his father. He was numb. He was transferred to the children’s block, where he remained with 600 others until April 11. That’s two and a half months, yet he tells us nothing of that time except that he did have an appetite and his only interest was getting an extra ration of soup. On April 5 (he knew the exact date) “we were inside the block, waiting for an SS to come and count us. He was late. Such lateness was unprecedented in the history of Buchenwald.”

Same problem as above: the official story (and Waltzer’s story) tells us that the communist “veterans” had these boys hidden away in the “small camp” where they cared for them, keeping them away from the SS and the camp authorities. We know that the SS did not go inside the blocks. Yet Wiesel writes that they did every day because on this day they were late. Covering for Wiesel, Waltzer writes on his website:

…the 16-year old Wiesel was assigned to a special barracks that was created and maintained by the clandestine underground resistance in the camp as part of a strategy of saving youths. This block, Block 66, was located in the deepest part of the disease-infested little camp, a separate space below the main camp at Buchenwald that was beyond the normal Nazi SS gaze (the local SS officer actively cooperated and conducted appels inside the barracks).

The barracks was overseen by block elder Antonin Kalina, a Czech Communist from Prague, and his deputy, Gustav Schiller, a Polish-Jewish Communist originally from Lvov. Odon Gati, a Communist from Budapest, was stubendienst. Schiller, who appears briefly in “Night,” was a father figure and mentor, especially for the Polish-Jewish boys and many of the Czech-Jewish boys, but he was less liked, and even feared, by Hungarian- and Romanian-Jewish boys, especially religious boys, including Wiesel. He appears in “Night” as a menacing figure, armed with a truncheon.

First, Waltzer mentions the underground. But they did not have the power to hide away the youths who were assigned to the special barracks 66. It was a policy of the Camp Commandant to separate these children to keep them safe, to feed them as well as possible, and they were fully aware of the children’s barrack 66 where they were kept. Thus. there may have been a “local SS officer” assigned to look after Block 66 to make sure everything was being done according to regulations … that is, even to supervise, to some extent, the communist block leaders. The story that it was the communists who “saved these boys from death” is a fiction that was created later, after the liberation of the camp and the formation of the Buchenwald association which was made up of former prisoners of communist persuasion. It was the camp authorities who made the decision to place the “children” away and apart from the adult prisoners, not the underground resistance.

Second, Wiesel writes in Night, “Gustav, the Blockälteste, made it clear with his club” that they had to obey the order to gather in the Appelplatz. Doesn’t this imply that the communist overseers were not necessarily acting as “father-figures” and mentors, but simply as guards? Also note that the kapo Gustav was carrying a club and used it, while earlier it was an “officer” in the barracks who wielded a club against Eliezer’s father. Relative to this, Ferenc Kornfeld reports : “Without exception, the Kapos all had big sticks.” He also said a Kapo armband went with a double food ration. And, “They continually shouted and they hit people on the head and the neck.” Kornfeld wrote about Buchenwald: “There were common criminals, murderers and thieves, in concentration camps too. They were called the “Blockältesters”. They were the “Kapos” (bosses). As they were murderers, they had black triangles on their uniforms. The Kapos hit and slapped all of us.” So much for the idea of Blockälteste’s as mentors.

The abrupt ending of Night

Wiesel claims on pages 114-15 (the last two pages of the book) that on April 5 everyone, even the children, were ordered to gather in the Appelplatz. On the way, some prisoners told them to go back because the Germans planned to shoot them. They turned around and on the way back they learned that “the underground resistance of the camp had made the decision not to abandon the Jews and to prevent their liquidation.” What kind of nonsense is this? Well, it is “the story” which evolved that these communists at Buchenwald finally, on the very last day, fought the Germans. What really happened was the Germans were ready to abandon the camp on the 11th, which they did. Wiesel simply picks up that official fiction of the underground resistance and incorporates it into his narrative. I don’t think the Germans ever intended to evacuate the children and youths.

Apparently, after the 5th, blocks of prisoners were being evacuated to other camps. By April 10, Wiesel writes, “we had not eaten for nearly six days except for a few stalks of grass and some potato peels found on the grounds of the kitchen.” From whom did these potato peels come? Did their communist keepers gather them and bring them to the youths inside the barracks? Did the boys roam around freely and eat grass? At ten o’clock the next morning, he tells us, the SS positioned themselves around the camp and began to herd the remaining inmates toward the Appelplatz. At this point the underground resistance members appeared “from everywhere” with guns and grenades. Eliezer and the other children “remained flat on the floor of the block.” (Therefore they saw nothing.) By noon, the SS had fled and the resistance was in charge. The first American tank arrived at 6 p.m.

Wiesel now wastes no time in concluding the book. He says he became very ill from food poisoning three days later because they “threw themselves on the provisions.” He spent two weeks in the hospital “between life and death.” One day he got up and looked in a mirror and saw only a corpse gazing back at him. This was at the end of April or first of May 1945. Yet he recovered so well that we see a healthy, smiling boy in the picture supposedly taken of him at Ambloy in late 1945 … or is it early or mid 1946?

It’s interesting that Wiesel made such a point later on of maintaining he had vowed in 1945 to wait ten years to write down his experiences. The reasons given, including that his memory would be sharper after ten years, are completely bogus—especially since his book bears little resemblance to the actual camps as we know them to be. The much longer Yiddish version was published in 1955-56. The abridged French version La Nuit in 1958; the English Night in 1960.

Conclusions

I have to say Wiesel doesn’t describe Buchenwald at all. You don’t know anything about Buchenwald from reading Night. You don’t learn much about Eliezer or anyone else. You are given an impression of suffering, without rhyme or reason, so Buchenwald becomes synonymous with suffering, that’s about it. We don’t know what it looks like. We don’t know the name or the physical appearance of any person, not even Gustav carrying a club, who is said elsewhere to have had red hair. Wiesel makes up a story about “an officer” using a club in the barracks when it could only be a kapo (if it was anyone at all). He doesn’t tell us anything about the children in the barracks where he stayed for 2 ½ months. He doesn’t describe the few days after liberation, before he got sick. One did not have to be at Buchenwald to write what he wrote!

Ken Waltzer also writes at his website:

Elie Wiesel has acknowledged the role played by the clandestine underground and political prisoners in saving children and youth at Buchenwald, especially in his autobiography, but he did not attend to this in “Night.” It was not his purpose or focus in that book. Many of his fellow barracks members, however, who are still alive and remember very well their days and nights in Block 66; their relations with Kalina, Schiller and others; and the hope provided to them there, have been helping fill in the story.

You can see a couple of these fellow barracks members here: Scroll down for Excerpts from the “Boys of Buchenwald” discussion panel (7.45 minutes) You can judge for yourself how impressive they are…or not. Neither one mentions Elie Wiesel.

Endnotes:

1. Elie Wiesel, Night, Hill and Wang, New York, 2006, 120 pgs.

2. This can refer to soup or disinfectant being available at the entrance to the barracks. Obviously, Eliezer and his father dawdling by having their long conversation caused them to miss out on both shower and whatever was in the cauldrons. Just another example of the intended vague descriptions permeating this book.

3. In the book, “coffee” is in quotes signifying it wasn’t real coffee. I left off the quote marks in the original writing because of the quote mark signifying the end of the sentence. Poor judgement on my part, but whether it was real coffee or not wasn’t the focus of my attention in this critique. However, the sharp attention of the author of the Scrapbookpages Blog picked up on this and wrote about Wiesel’s failure to know that real coffee was not served in the camps. My apology to “Furtherglory” for misleading him and to my readers also. I have added the quote marks since reading the blog at Scrapbookpages Blog.

17 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: And the World Remained Silent, Buchenwald, Elie Wiesel, Gustav Schiller, Ken Waltzer, Night,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Tuesday, July 12th, 2011

By Carolyn Yeager

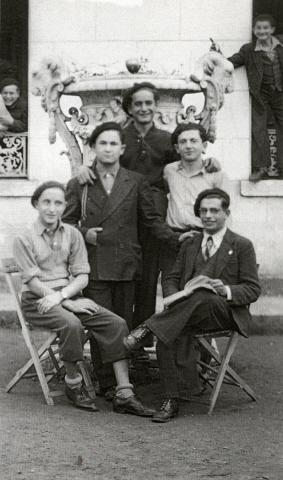

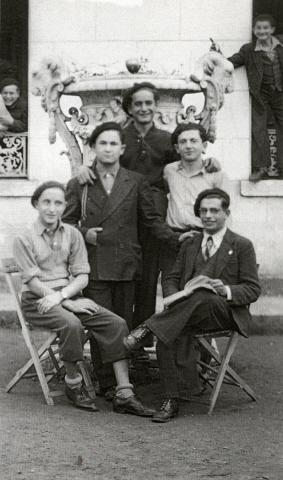

Pictured: front left, Kalman Kalikstein; Binem Wrzonski (middle right), and Elie Wiesel (back center).

This picture is now available for purchase at the USHMM website. The information about it is given as follows:

Date: 1945-1946

Locale: Ambloy (Loir-et-Cher) France

Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Binem Wrzonski

Copyright: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Title: Group portrait of boys in the Ambloy children’s home.

USHMM Commentary: In June 5, 1945, Binem joined a group of boys and young teenagers, known as “The Buchenwald Boys” who were brought to France in a special convey under the sponsorship of the O.S.E. They first were brought to Ecouis in Normandy. An aid worked (sic) helped Binem to make contact with his one surviving sibling, Towa who had spent the war in the Soviet Union. From Ecouis the children were taken to either secular or religious homes. Binem at first wanted to go to a secular home, but Leo Margolis, a German Jew who was in Buchenwald for approximately six years and helped care for the children, persuaded him to go to a religious home. Binem then went to Chateau d’Ambloy. From there he went to Taverny. Then together with two other teenagers, with Elie Wiesel and Kalman Kaliksztajn, he accompanied a group of younger boys to Chez Nous in Versailles where worked as a counselor. From this experience, Binem decided to become a teacher. After training in France, he immigrated to Israel and became the principal of a Youth Aliyah boarding school. In Israel he met and married Rahel Schlezinger and they went on to have five children and many grandchildren and great-grandchildren. In 1983 Binem returned to Lodz and erected a new marker at his father’s graves including the names of all of his family members who died during the Holocaust. [end of USHMM commentary]

* * * *

Binem came from Buchenwald, but not Elie Wiesel and maybe not his good friend Kalman!

What is amazing about this commentary on the picture above is that Elie Wiesel is NOT said to have been at Buchenwald with Binem, but encountered him at Taverny. Elie and Kalman, according to Binem, accompanied a group of younger boys to Chez Nous in Versailles where they worked as counselors. This actually makes a lot more sense. A narrative in which Elie Wiesel is not a withdrawn, scarred youth from the concentration camps, but possibly arrived in France sometime during the war—helped by the Jewish network and placed in the children’s welfare institutions—is quite possible. There, he associated with some of the youths who were sent after the war, and developed his “knowledge” of concentration camp life from them.

Is this why he had no interest in gaining French citizenship—because he was devoted to the Jewish cause of Eretz Israel and always connected to and working with the Jewish Underground? (See Elie Wiesel and the Mossad)

Was Elie Wiesel actually a youth counselor for Buchenwald boys, rather than one of them?

Can this explain why he remained with the welfare agencies for so long and was one of the oldest to leave his last home at Versailles to live on his own? His friend Kalman left for Israel in 1947 before Elie managed to get a room of his own “at the end of summer” at the age of 19. This would have been after his birthday on Sept. 30.

Compare this photograph with the one below, which the USHMM identifies as:

Group portrait of the staff and boys of Ambloy, an OSE home for religious youth.

Among those pictured are (First row, left to right): Natan Szwarc, Izio Rosenman, Deblin, unknown and perhaps Berek Rybsztajn. (Third row): Abraham Tuszynsky (2nd from left, first boy next to woman), Andre Zelig is in the center with a tie and his hands on the boy in front of him and Elie Wiesel (second right of Tuszynsky). Binem Wrzonski is to the right of Elie Wiesel. The donor, Jakob Rybsztajn is in the fourth row, fifth from the left.

This picture is available for purchase from USHMM website. The information given about it is as follows:

Date: 1945

Locale: Ambloy, (Loir-et-Cher) France

Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Jacques Ribons

Copyright: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

The inscription on the back reads “Before our departure from Chateau Ambloy for Paris.”

USHMM Commentary: Jakob Rybsztajn (now Jacques Ribons) is the son of Peretz Rybsztajn (b. 1905) and Bella (Bajal, b. 1906) Rybsztajn. He was born on August 15, 1927 in Strzemieszyce Poland where his father was a textile manufacturer. He had two younger siblings: Bernard (Berek) who was born in 1929 and Esther who was born in 1935. In 1933 the family moved to Zelow, Bella’s home town. The family remained there until 1936 when it moved back to Strzemieszyce. In 1939 Germany invaded Poland later the Rybsztajns were forced to move to a ghetto. Jakob attended a ghetto Hebrew school. Peretz Rybsztajn, his father, worked with or was close with the Jewish Council but he soon disappeared. After the ghetto was liquidated, probably in June 1943, Jakob and Berek, who initially had hid, were forced to return and then sent briefly to Bedzin. In September they were deported to the Blechhammer concentration camp where they were forced to work unloading cement from train cars, insulating oil and fuel tanks with asbestos, and cementing steel forms to the tanks. They lived in a barrack with other boys their ages, including Kalman and Heniek Kaliksztajn, two brothers also from Strzemieszyce. In January 1945 the Germans liquidated the camp in advance of the Soviet army, and the brothers were sent on a death march via Gross Rosen and by open train to Buchenwald. They arrived in Buchenwald on February 10, 1945, and were placed in the children’s block, Block 66.

Jakob and Berek remained together in block 66 until they were liberated in Buchenwald by the U.S. Third Army in April. The boys in the barrack, under the supervision of Gustav Schiller, the deputy block elder, did not work and received occasional Red Cross packages distributed from other prisoners in the camp. After liberation, the Rybsztajn brothers joined a children’s transport to Ecouis in France, sponsored by the O.S.E., where they were through the summer. But, as they were religious, they were sent from there with other religious boys, including the Kaliksztajn brothers, also Elie Wiesel, to children’s homes in Ambloy and Taverny. Then Jacques came to Paterson New Jersey and later enlisted in US army during the Korean conflict. He arrived in New York in February 1947 on board the Gripsholn, a Swedish ship. Berek was adopted by the Homberger family in California. Later he was in Israel and served in the Israeli Defense Forces; he returned to California in the late 1950s. Jacques also settled in Los Angeles. The Rybsztajn parents, Perez and Bella Rybsztajn, and their sister younger sister Esther perished in Auschwitz, it is believed, during 1943. [end of USHMM commentary]

* * * *

If it can be proven that this is indeed Elie Wiesel in the two pictures, we still do not know if he arrived in Ambloy from Buchenwald.

We have learned that others were there already and the Buchenwald boys joined them. He may have been one of those who were already there. The commentary states as an afterthought that “also Elie Wiesel” was among those sent to Ambloy and Taverny. Where are the records that must have existed? In what capacity was Elie Wiesel there?

The person identified in each photo above as Elie Wiesel is dressed in the same clothing, so the pictures were most likely taken on the same day. The boy Binem may simply have taken off his jacket in the more casual top picture. But where is Kalman in the large group photo? He is not identified and appears to be missing. Rather than pictures on more than one occasion, we have two different pictures taken at the same time.

The group is dressed for travel to Paris (Versailles). It must have been later than 1945 that they transferred to the home in Versailles, so this picture should probably be dated 1946, as is the top picture. All of these questions I raise show the poor scholarship done by the USHMM and the holocaust historians in general. Slip-shod reporting is picked up from here and there, thrown together, becoming the “story” that fits the bill. Thus we have Elie Wiesel’s name stuck in where they want it to be, to try to show that he was one of the Buchenwald boys, when actual proof doesn’t exist.

These photographs only portray someone who could be Elie Wiesel at a home in Ambloy, France where some of the boys from Buchenwald, and also Jewish boys from elsewhere, lived for a time.

As far as the next picture is concerned, I now cannot be sure that these boys are arriving from Buchenwald. They are only identified as Jewish DP (displaced persons) youth at the USHMM website:

Group portrait of Jewish DP youth at the OSE (Oeuvre de Secours aux Enfants) home for Orthodox Jewish children in Ambloy. Elie Wiesel is among those pictured. [Photograph #28147]

This photo is also available for purchase at USHMM website. The information given about it is as follows:

Date: 1945

Locale: Ambloy, (Loir-et-Cher) France

Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Robert Waisman. Willy Fogel

Copyright: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

In this case, none of the boys are identified by name. In the long commentary that accompanies the picture on the page, there is no mention at all of Elie Wiesel. I will say that no one in this picture is wearing a beret! Once again, if the USHMM or Prof. Ken Waltzer claim that Elie Wiesel is in this picture, they must point him out.

It has never been disputed that Elie Wiesel was in France. But just when he arrived and what he was doing there is not documented.

* * * *

The next step for the reader is to compare the face of “Elie Wiesel” in the first two photos above with the faces of “Elie Wiesel” in the famous Buchenwald photo and the boys marching out of the Buchenwald gate, plus his portrait as a 15-year-old, that are found at “The Many Faces of Elie Wiesel.” They can’t all be Elie Wiesel. It’s up to you—and up to USHMM and Ken Waltzer, and how about the old liar Elie Wiesel himself!—to decide and announce which ones are. When that is clear, we can then decide what the pictures are telling us.

10 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: Ambloy, Binem Wrzonski, Buchenwald, Elie Wiesel, Jacques Ribons, USHMM,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.