Posts Tagged ‘Buchenwald liberation’

Tuesday, June 11th, 2013

[Continuation from “Is it time to call Ken Waltzer a fraud?“]

by Carolyn Yeager

by Carolyn Yeager

copyright 2013 carolyn yeager [last updated 12-5-2015]

“In literature, Rebbe, certain things are true though they didn’t happen, while others are not, even if they did.” –Elie Wiesel speaking of his book Night, from his Memoir: All Rivers Run to the Sea

For the skeptics and know-nothings who have written in suggesting Eli Wiesel was not in the camps, that Night is purely fiction, you are all dead wrong. The Red Cross International Tracing Service Archives documents for Lazar Wiesel and his father prove beyond any doubt that Lazar and his father arrived from Buna to Buchenwald January 26, 1945, that his father soon died a few days later. –Kenneth Waltzer in a comment at Scrapbookpages Blog, March 6, 2010.

The story that Michigan State University history professor Kenneth Waltzer has told us about Elie Wiesel in Buchenwald, based on Wiesel’s book Night, is not true.1

Elie Wiesel was not incarcerated at Buchenwald.

He was not liberated from Buchenwald.

He was not a victim of the “Nazis” there.

How do we know that?

Well, how do we know that Elie Wiesel was at Buchenwald?

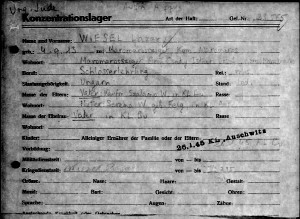

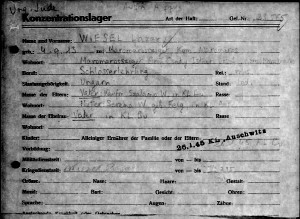

1. We have a numerical file (registration) card for Lazar Wiesel from Sighet, born 1913.

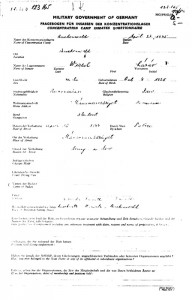

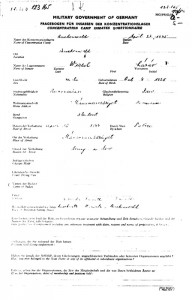

2. We have a questionaire (Fragebogen) made out for and signed by a Lázár Wiesel, a 16-year old Jew from Sighet.

3. We have a transport list from Buchenwald to France with the name Lazar Wiesel, born Oct. 4, 1928.

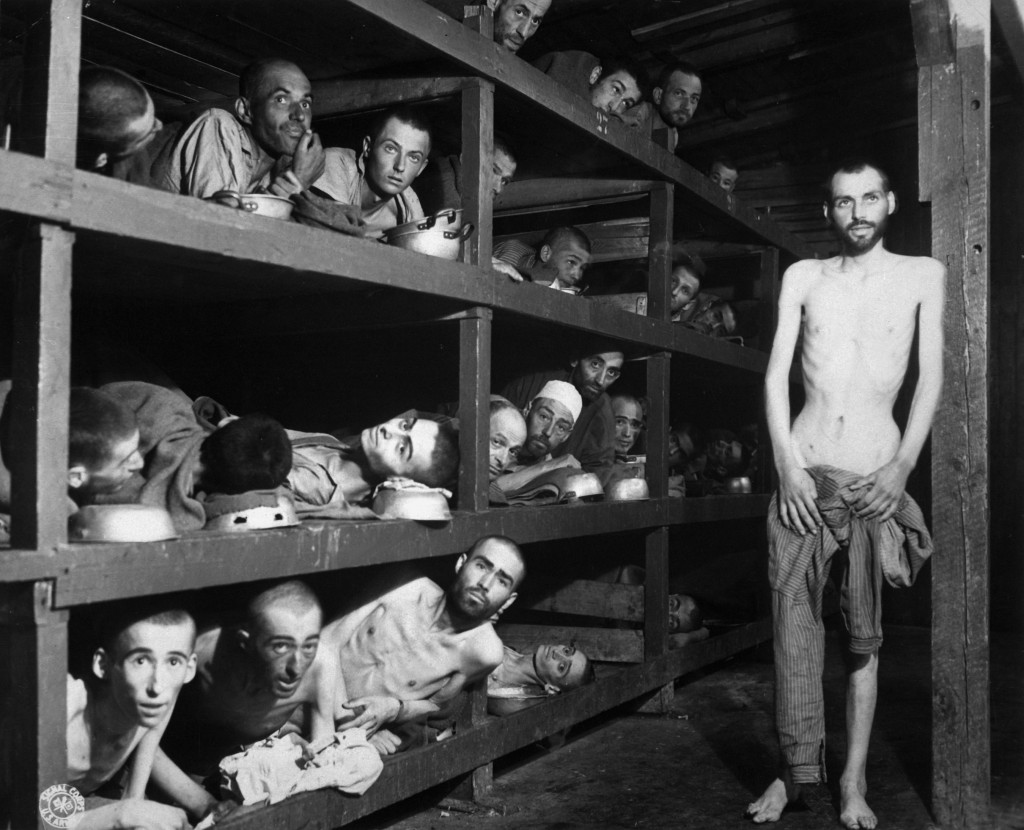

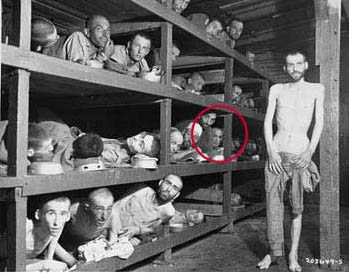

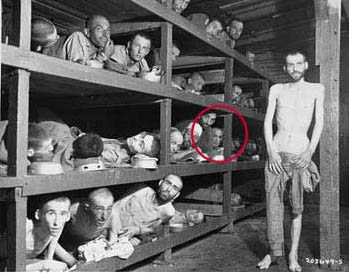

4. We see a picture of him in the famous photograph taken in Barracks #56 on April 16, 1945.

5. We have a death report for Abraham Viezel (not Schlomo or Solomon) on 2-2-1945, in Block 57.

6. We have a transport list from Auschwitz to Buchenwald with the names Lazar Wiesel, #123565, born 4 September 1913 and Abram Viezel, #123488, born 10 October 1900.

7. We have a photo of the “rescued children” marching out of the Buchenwald main gate on April 27, 1945.

8. We have the book Night, in which he says he was.

* * *

The above list is ordered according to its perceived importance in proving Wiesel was at Buchenwald, so I’ll start from the bottom (least important) in showing that they don’t prove any such thing.

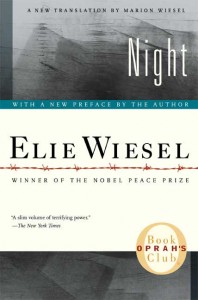

8. The persuasiveness of the book Night has been dealt with in several other places, for example here and here, and is not considered evidence.

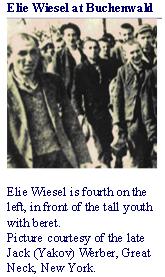

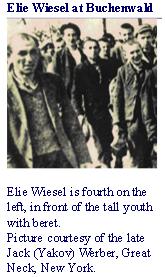

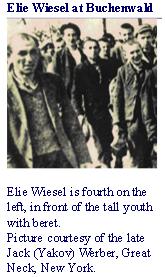

7. Photo of Buchenwald Boys (scroll down a bit). The boy that Ken Waltzer has identified as Elie Wiesel (who was identified to him as such by Jack Werber of Great Neck, NY, a “holocaust survivor” activist) is clearly not Wiesel and has not been identified as Wiesel by anyone other than Ken Waltzer. Waltzer had this image/blurb, at right, on his MSU website for years [the site was removed sometime in 2012], making him look foolish. Will Waltzer admit that he was wrong all this time, or try to sweep it under the proverbial rug?

7. Photo of Buchenwald Boys (scroll down a bit). The boy that Ken Waltzer has identified as Elie Wiesel (who was identified to him as such by Jack Werber of Great Neck, NY, a “holocaust survivor” activist) is clearly not Wiesel and has not been identified as Wiesel by anyone other than Ken Waltzer. Waltzer had this image/blurb, at right, on his MSU website for years [the site was removed sometime in 2012], making him look foolish. Will Waltzer admit that he was wrong all this time, or try to sweep it under the proverbial rug?

6. The Transport List to Buchenwald only proves that Lazar Wiesel, age 31 (a locksmith by trade) and Abram Viesel, age 44, arrived at Buchenwald on January 26, 1945 from Auschwitz. See here and here. Elie’s father’s name was Solomon (Schlomo); he never went by Abram, nor did Elie ever go by “Lazar.” Lazar had been given the Buchenwald number 123565, while Abram had 123488. There is no honest way to turn these two into Eliezer Wiesel and his father. Both the birth dates and the names are wrong. It only proves that Elie Wiesel claimed for himself the Auschwitz prisoner number (A7713) of another man. Where is the tattoo on Elie’s arm that reads A7713?

5. The Death Report for Abraham Viezel, Buchenwald prisoner number 123488, same as on the transport list. His death is recorded as taking place in Block 57 on February 2, 1945, not Jan. 29, 1945 as is clearly stated in Night for Eliezer’s father.2

4. The Famous Liberation Photo taken at Buchenwald on April 16, 1945 is said to show Elie Wiesel among the men in the bunks. Beside the fact that the face pointed out as Elie’s doesn’t look like him (for reasons which have been made clear here and here) and that he did not identify himself in it until 1983 when the campaign to get him a Nobel Prize began, there is also his hospitalization which began on April 14th.3 He could not have been near death in a hospital and in the picture at the same time! Ken Waltzer took the liberty of changing the date the photo was taken to April 12 or 13th to get around that inconvenient fact.4

3. The Transport List to France. When did Elie Wiesel’s birthday change to Oct. 4th from Sept. 30th? A majority of boys on this list share the birth year of 1928. The person listed as Lazar Wiesel is the same Lazar Wiesel that the Questionaire refers to, but we have determined that this person could not have been Elie Wiesel. It is true that Elie Wiesel went to France, but how he got there, and when, is not clear.

2. The Questionaire [scroll down page] was apparently prepared for and signed by every prisoner prior to their release. It is dated April 22, 1945; the prisoner number is 123165, different by one digit from our previous Lazar Wiesel #123565, and is the number belonging to a recently deceased inmate, Pavel Kun,5 whose death is recorded as March 8, 1945. Since Elie Wiesel allegedly received his number upon arrival on Jan. 26, 1945, he would not later be given a new number from a prisoner who just died. It would seem from this that Lázár Wiesel is a newcomer-of-sorts who had been given a number that had just been released.

2. The Questionaire [scroll down page] was apparently prepared for and signed by every prisoner prior to their release. It is dated April 22, 1945; the prisoner number is 123165, different by one digit from our previous Lazar Wiesel #123565, and is the number belonging to a recently deceased inmate, Pavel Kun,5 whose death is recorded as March 8, 1945. Since Elie Wiesel allegedly received his number upon arrival on Jan. 26, 1945, he would not later be given a new number from a prisoner who just died. It would seem from this that Lázár Wiesel is a newcomer-of-sorts who had been given a number that had just been released.

The name Lázár is spelled with distinct, heavy accent marks; the birth date given is Oct. 4, 1928 (Elie’s is Sept. 30); date of arrest is April 16, 1944 (Elie’s family’s deportation was at the end of May/early June – see here); the signature on the back does not match Elie Wiesel’s known signature or handwriting. The signature is also written with accents over the a’s in Lázár, implying that the accenting originated with Lázár and not with the official who filled out the form.6

But, beyond all this, on April 22 Elie Wiesel, by his own account, was in a hospital in or near Buchenwald camp “hanging between life and death” after coming down with severe food poisoning. He was taken to the hospital on April 14 and not released until April 28, according to his own words in his “autobiographical” Night and his 1995 memoir All Rivers Run to the Sea. Therefore, he could not have been interviewed or signed the questionaire on April 22nd. (See Endnote 3)

1. The Numerical File Card (below), made out at registration, is for Lazar Wiesel from Maromarossziget, born Sept. 4, 1913, making him at the time 31 years old. His Buchenwald prisoner number 123565 is written on the upper right. The card indicates his father, Szalamo Wiesel, was also at Buchenwald, while his mother, Serena Wiesel, nee Feig was currently interned at KL Auschwitz (at the time of Jan. 26, 1945).

This registration card is the only item that casts some doubt7 over Nikolaus Grüner’s account of Lazar and Abram. But it does not prove that this Lazar Wiesel is Elie Wiesel. It does not make any sense that all the birth dates for the same person would be different! It makes more sense that there were several persons with similar names.

This registration card is the only item that casts some doubt7 over Nikolaus Grüner’s account of Lazar and Abram. But it does not prove that this Lazar Wiesel is Elie Wiesel. It does not make any sense that all the birth dates for the same person would be different! It makes more sense that there were several persons with similar names.

Note that this card identifies Lazar Wiesel as a locksmith (Schlosserfehrling), a trade of which the 15-year-old Elie Wiesel never would have identified himself. In Night he identified himself upon entry to Auschwitz as “a farmer” (p. 32, MW translation) and continued not to boast of any skill (of which he had none anyway) so as not to be sent out for work.

* * *

So we end up realizing there is no evidence that Elie Wiesel ever set foot in Buchenwald in 1945. What’s more, he and others (including Ken Waltzer) have actively and knowingly lied about photographs, dates, times, names, etc. This has gone on with the blessing and support of Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial in Israel, the US Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington DC, the New York Times Company, Associated Press, and other establishment media – and the multitude of Jewish/Holocaust-promoting organizations across the globe. Think of Elie Wiesel conducting US President Obama and German Chancellor Merkel around the Buchenwald Memorial in 2009! It is a giant criminal conspiracy when one really takes a look at it. The ramifications are immense.

Someone, preferably Elie Wiesel, needs to explain all the discrepancies in his tale. He has never offered to and never been asked to. If Wiesel won’t attempt an explanation, then Ken Waltzer the Historian with the PhD from Harvard University must do so. In his scholarly studies, Waltzer includes Elie Wiesel as one of the “Rescued Children of Buchenwald. ” One duty of a scholar is to answer serious and justified questions about their work. Elie Wiesel Cons The World is asking such questions and so we await an answer.

Update 6-15 Great idea from a reader: Write to Prof. Ken Waltzer at [email protected] and ask him politely to answer the questions raised in this article.

Endnotes:

1. Prof. Kenneth Waltzer has removed this article from the Internet, along with his entire website which the article had been a part of for several years, and says he has written a new separate article on Elie Wiesel in Buchenwald.

The book is on track, and I have also completed a separate essay to be published on Elie Wiesel and Buchenwald. -Ken Waltzer to me, Carolyn Yeager, in an email, March 2013

He obviously doesn’t want comparisons made between his old and new article and is waiting as long as possible to make it public. Or is he still reworking it?

2. “Then I had to go to sleep. I climbed into my bunk, above my father, who was still alive. The date was January 28, 1945. I woke up at dawn on January 29. On my father’s cot there lay another sick person. They must have taken him away before daybreak and taken him to the crematorium.” –Night, 2006 Marion Wiesel translation, p. 112

The Yiddish original, Un di Velt Hot Gesvign, says Father’s death occurs on the 18-19 of Shevat:

For a couple of hours I stayed by him and looked at his face long and well […] Then they forced me to go lie down to sleep. I climbed up to the uppermost bunk and I did not know that in the morning, on awakening, I would find my father no more.

It was the eighteenth of Shevat, 5705.

Nineteenth of Shevat. Early in the morning.

I got up and ran to my father. Another sick man was lying in his place.

I had a father no more. (p 238)

Readers might be surprised to learn that the Hebrew calendar date of 18-19 Shevat, 5705 corresponds to February 1-2, 1945. This gives credence to the idea that Abram Viezel’s death is the model for the story And The World Remained Silent. The date in the original story for Father’s death and the date of Buchenwald records for Abram’s death concur. This leads me to question Elie Wiesel’s personal knowledge of events at Buchenwald because why would he change the date to Jan. 28-29 if he knew the significance of Feb. 1-2?

Also, the death took place in Block 57, the report said, which would seem to be next door to Block 56 where the famous Buchenwald liberation photo is said to have been taken.

3. “Three days after the liberation of Buchenwald, I became very ill: some form of food poisoning. I was transferred to a hospital and spent two weeks between life and death.” –Night, 2006 Marion Wiesel translation, p. 118

Also in Un di Velt Hot Gesvign (the original Yiddish story from which Night was taken), p.244:

“Three days after liberation I became very ill; food-poisoning. They took me to the hospital and the doctors said that I was gone. For two weeks I lay in the hospital between life and death. My situation grew worse from day to day.”

Another question that occurs is: Of all the photos taken in Buchenwald after liberation, why don’t we find even a single one with Elie Wiesel in it? Knowing he wasn’t there at all may be why he liked the food poisoning/hospitalization story – it can explain why he doesn’t show up in any photograps. But it totally contradicts his “evidence” of the Questionaire and of his being in the famous barracks #56 photo.

4. Waltzer wrote in his article:

“He [Elie] was too weak at liberation on April 11 to leave his barracks (hence he was photographed in a famous picture in the barracks on April 12 or 13), and he came to understand he was free only days later.”

Waltzer trapped himself again. The officially declared date of the photo is April 16, which is well established. Waltzer is simply trying to evade with lies the serious problem of Wiesel going into the hospital 2 days before the photo was taken. This is NOT how a respectable, responsible historian does things.

In addition, Waltzer is saying that the photograph was taken in the children’s barracks #66, which is utterly wrong. The official description says it was barracks #56, for men, or possibly a sick barracks. If Abram Viezel was in a sick barracks when he died (#57), then #56 might also be an “infirmary” barracks.

5. Pavel Kun is on the transport list of Jan. 26, 1945 from Auschwitz to Buchenwald. He appears under the section Politische Slowakan Juden; his birth date is July 6, 1926, making him 18 when he died.

6. Revisionist Carlo Mattogno concluded, after studying these documents, that Lazar Wiesel, Lázár Wiesel and Elie Wiesel are not the same person.

In conclusion, we can say that Elie Wiesel can be neither Lazar Wiesel, nor Lázár Wiesel, nor Lazar Vizel and that the ID number A-7713 was not assigned to him but to Lazar Wiesel, while ID A-7712 was not assigned to his father but to Abram (or Abraham) Viesel (or Wiesel).

The charge of identity theft raised against Elie Wiesel by Miklos Grüner does not concern Lazar Wiesel only, but Lázár Wiesel as well: from the former, he took the Auschwitz ID number (A-7713), from the latter the stay at Buchenwald and the later transfer to Paris. –http://revblog.codoh.com/2010/03/elie-wiesel-new-documents/#more-837

7. Szalamo seems likely a Hungarian spelling for Shlomo. Serena Feig is close but not Elie’s mother’s name, which was Sarah Feig. According to this card, Lazar had a father in the camp, something that was not mentioned by Nikolaus Grüner. Ken Waltzer will say this proves that Lazar Wiesel is Elie Wiesel, but what about the very wrong birthdate? Why don’t we have a card for Szalamo too? These cards are kept at Bad Arolson, not at the Buchenwald Memorial Museum Archive; only people with special permission (like Waltzer) have access to them.

17 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: Abramham Viezel, Buchenwald Boys, Buchenwald liberation, Elie Wiesel. Buchenwald Concentration Camp, Kenneth Waltzer, Lazar Wiesel, Night, Rescued Children of Buchenwald,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Sunday, April 14th, 2013

By Carolyn Yeager

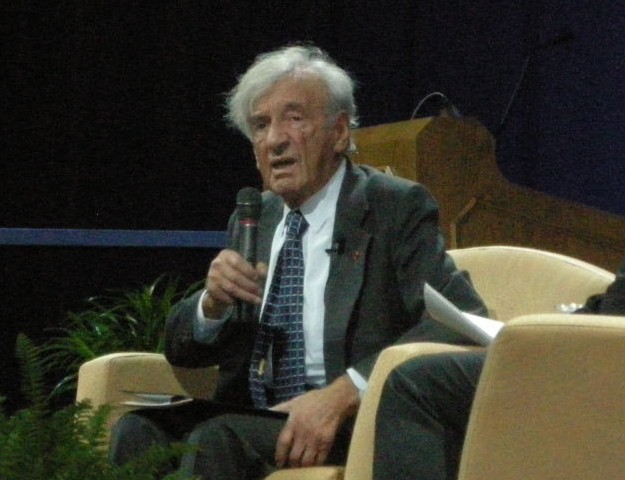

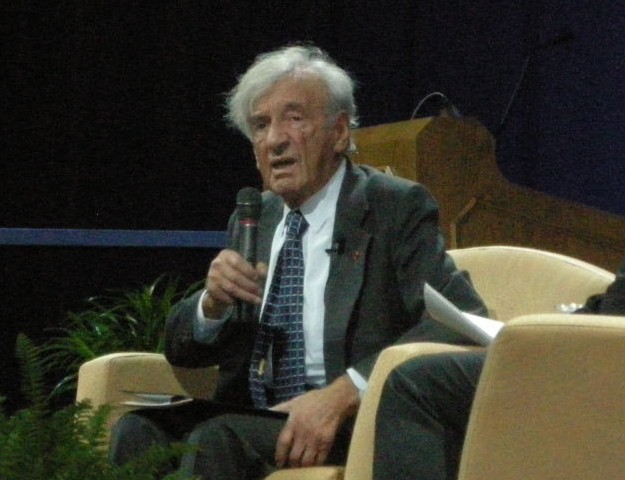

Elie Wiesel in the Kent State Univ. auditorium. Photo by Bob Jacobs

Wiesel demonstrates he has nothing to say to the world when the only news outlet to write anything at all about his speech is the Cleveland Jewish News.

This much-ballyhooed return visit to Kent State University on the April 11 anniversary of the “Buchenwald Liberation” in 1945 proved to be as “much ado about nothing” as the earlier event 68 years ago really was in retrospect.

Wiesel, 83, looking tiny and munchkin-like sitting in a big yellow chair on the stage, uttered the same phrases we’ve heard for decades and they are sounding more hollow than ever. At kentwired.com, [www.kentwired.com/latest_updates/article_25df8c65-c166-57b2-9a99-b89175cd7a3c.html] a University website, we find this summing up of the speech:

One of the major themes of Wiesel’s speech was the importance of having hope and his struggle with believing there is such a thing.

“Where there is no hope, our road and our path is to invent it,” Wiesel said. “I am here to teach you my hope because without it, I wouldn’t be here today.”

Invent it. That’s what Wiesel is good at: inventing things. He offered other similar thoughts that Kentwired considered worthy of quoting but are, in my opinion, devoid of any relevance when pondered for a few seconds, such as:

“For every word that a holocaust survivor writes, there are 10 more that haven’t been written,” said Wiesel. “Whoever listens to a witness becomes a witness.”

My comment on the first sentence: This is true of everyone’s written words. On the second: This well-worn phrase of his might be what is engraved on his tombstone – he has used it so often. Of his supposed liberation by U.S. soldiers at Buchenwald, he said:

We had lost every concept of how to feel. We did not know what it was like to be free.

“I believe in the virtue of gratitude,” Wiesel said. “Simply to say to each other, thank you.”

The first is patently false. It discounts all the uprisings that supposedly took place, all the resistance activity in the camps, and the fact that Wiesel only claims to be a detainee for one year. One doesn’t lose memory of freedom in one year. The second bit of wisdom takes care of not answering questions about Buchenwald nicely, doesn’t it.

At the Cleveland Jewish News (CJN), reporter Carlo Wolff ([email protected]) tries to build up the importance of Wiesel’s utterances by writing that he “delivered a lesson in history, literature, philosophy and morality, demonstrating his didactic prowess and his belief in the power of continuity.” I must not be intelligent enough to grasp the greatness of this speech, which Wolff tells us was appreciated by “a rapt, sell-out audience of 5000” … mostly fellow Jews, I would say. I’m convinced that Jews from all around the broader area drove to Kent to see, hear and support one of their own, who has always fought for Jewish and Israeli interests.

No one noticed Wiesel’s mic was off for first 20 minutes

But Wolff had enough of the journalist in him to tell us about the following screw-up that must have embarrassed Kent State President Lester Lefton, also a Jew and the man who invited Wiesel to the campus.

The first 20 minutes of Wiesel’s April 11 talk almost fell on deaf ears because his microphone wasn’t turned up; most followed his eloquent words as they scrolled out on giant screens flanking the stage.

According to Wolff, Wiesel didn’t refrain from his familiar finger-pointing at the Germans.

He remains appalled by the Nazis. “The enemy managed to push its crimes beyond language,” he said, explaining the difficulty he has (and the obsessions that dog him) in telling a story that can never ultimately be told.

“They had education. They had degrees. So what happened?”

What happened? Their education helped them see clearly that Jews were a danger to their German social order – and so they were, and are. It is really only Jews who commit crimes “beyond language,” if such a thing exists. It is Jews in Israel that force pornography into Palestinian homes via their television sets, at the same time they are attacking them militarily. Only Jews would dream up something like that. Likewise, only Jews would dream up the kind of concentration camp atrocity stories they tell, atrocities that Germans, Nazi or not, would never think of themselves, and therefore never do.

Tweeting the most pithy remarks of the evening

Kentwired had someone tweeting the highlights of the evening as it progressed. Here is an example of the “best of Elie Wiesel”:

- “My first passport was an American one. It’s still a symbol of human passion,” said Wiesel. “I owe America.”

- “Remember there will always be questions that have no answer,” Wiesel speaking about his experience as a Holocaust survivor.

- “I believe in memory because without it nothing is possible.”

- “The moment we stop remembering, we stop believing.”

- “Could humanity get Alzheimer’s? Could history get Alzheimer’s?”

- “History has gone beyond its limits and therefore forget it no more,” Wiesel says on making sure people don’t forget.

- “The love of children is the purest of all,” says Wiesel on trying to understand why children were killed during holocaust. [Wiesel had one child who grew up to go to work for Goldman Sachs – cy]

The following were probably answers to softball questions from the audience:

- “History has not found balance,” said Wiesel on all the chaos in the world. “We are still waiting for redemption.

- “I simply feel, again, that I have done something,” said Wiesel on his many honors and awards

- “I couldn’t be who I am if not for those books,” said Wiesel on the many books he’s written

Have you had enough? It doesn’t get any better. And it all sounds very similar to Wiesel’s speech last year at Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio. To sum up, Wiesel is a fading star who may not last much longer. What can last is the incredible mythology built up around him unless we work very hard to separate reality from nonsense. This takes a consistent effort, not once-in-awhile comments about the same old themes. As we can see, that is actually Wiesel’s style and it’s not very effective. When it comes to the Elie Wiesel myth, it’s the media that has done all the heavy-lifting, not E-lie himself.

This time, even the media didn’t have an appetite for it.

6 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: Buchenwald liberation, Carlo Wolff, Elie Wiesel, Kent State University, Lester Lefton, Palenstinians,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Monday, April 1st, 2013

By Carolyn Yeager

copyright 2013 Carolyn Yeager

Updated April 7th

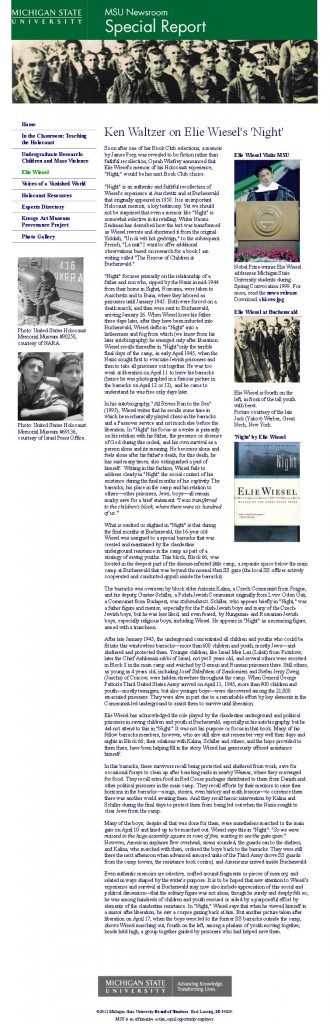

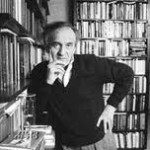

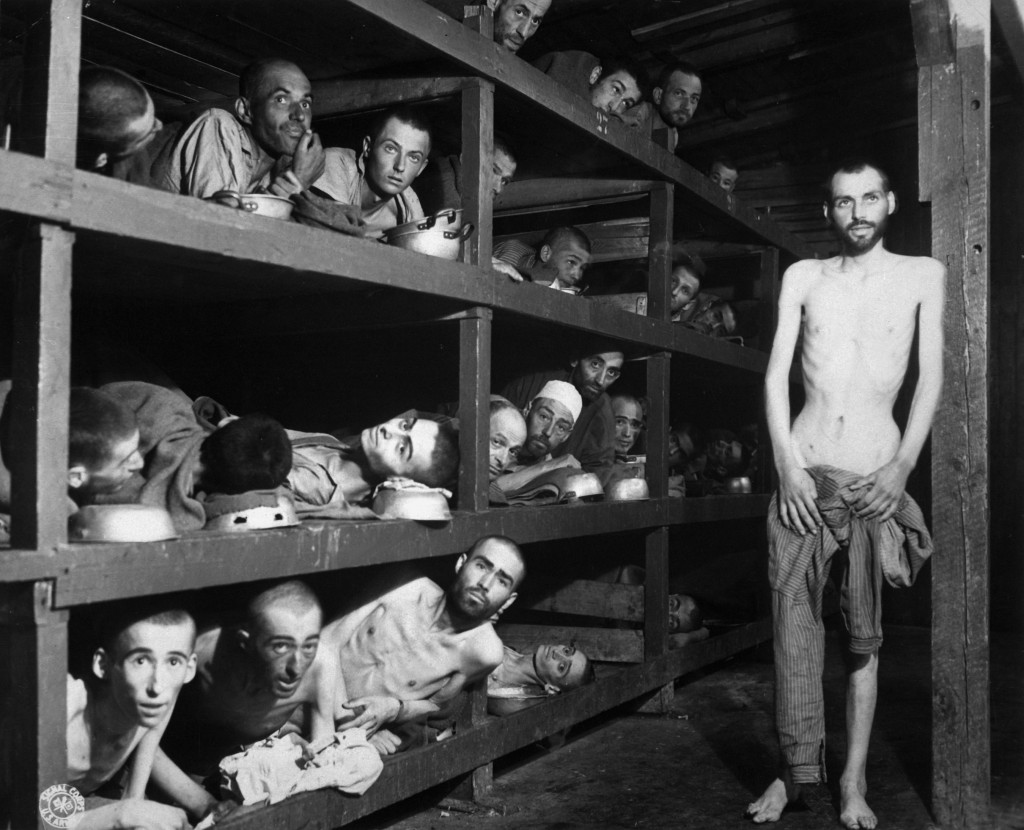

Prof. Kenneth Waltzer is looking at a Buchenwald registration card at the International Tracing Service in Bad Arolsen, Germany.

Kenneth Waltzer is a professor of history at Michigan State University since the early 1970’s. He helped to create the Jewish Studies program which opened in 1992, and which he heads. Waltzer has been researching into evidence of a special ‘boy’s protection program’ run by prisoners at Buchenwald for going on 10 years now. As an “approved” researcher, he is allowed to peruse all the files at the International Tracing Service in Bad Arolsen, Germany, something that is made much more difficult, if not impossible, for revisionists.

Waltzer is considered one of the top scholars in the U.S. of the ill-named holocaust but his work has been sloppy, and his attempts to cover up the sloppiness amount to fraud. This, along with his continual promotion and defense of Elie Wiesel as a Buchenwald survivor, is what has drawn me to study him ever more closely.

Because of the seriousness of the charge I am making against him, I will list right up front my reasons for thinking it is time for such a call. They are:

- Waltzer habitually tells fibs in the form of false information which is intended to mislead. When called out for it, he tells more fibs to cover for the first ones.

- He has been in the service of the “Holocaust Industry,” not academic rigor and fair-mindedness, from the very start of his career.

- He knowingly defrauds his students, his university and the public (you and I) with his dishonest “holocaust scholarship.”

- While he is drawing high pay as a tenured American professor of history at MSU, he is working to advance the State of Israel.

I am going to show that these charges have a strong basis in fact. Fraud is commonly understood as dishonesty calculated for advantage. A person who is dishonest may be called a fraud. In the U.S. legal system, fraud is a specific offense with certain features. (see here)

Legally, fraud must be proved by showing that the defendant’s actions involved five separate elements: (1) a false statement of a material fact, (2) knowledge on the part of the defendant that the statement is untrue, (3) intent on the part of the defendant to deceive the alleged victim, (4) justifiable reliance by the alleged victim on the statement, and (5) injury to the alleged victim as a result.

I am not intending to bring legal charges of fraud against Prof. Waltzer, but to try him in the court of public opinion. Therefore, it will be up to Waltzer to defend himself against my charges.

* * *

Two years ago, I asked the question on this web site: “What happened to Ken Waltzer’s book about the boys of Buchenwald?” It was claimed to be, at that time, in it’s final stages. Eight years after he publicly announced he was researching for a book about the so-called children’s barracks at Buchenwald (Barracks #66 ), it still has not materialized. Five years after his book was described as “upcoming,” it still has not materialized. During this time, he has not produced another book, or any major work that would have taken precedence over this book. So what is the delay?

It’s pretty plain that the book’s thesis has shifted considerably since 2005, when his MSU website featured Elie Wiesel as the most recognizable and famous child survivor from Buchenwald. That website was taken down between one and two years ago and is completely wiped clean from the Internet. The banner on all the six to eight pages that were included showed a photograph very similar to the one below of the “boys” being marched out of the main Buchenwald camp to temporary quarters at the former SS barracks.

The USHMM (national holocaust museum in D.C) website dates this picture as being taken on April 17, 1945, six days after liberation.1 At this time, Elie Wiesel, by his own account in two books, was laying in a hospital sick almost unto death from food poisoning. Details like this don’t deter Prof. Waltzer from backing up in every instance the standard holocaust narrative. “Elie Wiesel in Buchenwald” is the standard narrative, so evidence must be found for it.

Ken Waltzer claimed for years that one of these boys was Elie Wiesel. But Wiesel is not in this picture!

Ken Waltzer claimed for years that one of these boys was Elie Wiesel. But Wiesel is not in this picture!

From at least 2005 (eight years now), Waltzer has identified the boy third from the front in the left-side column (dressed in a black suit, bareheaded, and in front of the tall boy wearing a beret) as Elie Wiesel, based on nothing but his own fraudulent intention that there was enough resemblance that people would believe it if he said so. In this article , I exposed this lie. Waltzer has never admitted that he was mistaken or was perpetrating a falsehood that he intended to put into his book. Instead, what he did when his fabrication was sufficiently exposed was to take the entire site down and not mention it again.

From at least 2005 (eight years now), Waltzer has identified the boy third from the front in the left-side column (dressed in a black suit, bareheaded, and in front of the tall boy wearing a beret) as Elie Wiesel, based on nothing but his own fraudulent intention that there was enough resemblance that people would believe it if he said so. In this article , I exposed this lie. Waltzer has never admitted that he was mistaken or was perpetrating a falsehood that he intended to put into his book. Instead, what he did when his fabrication was sufficiently exposed was to take the entire site down and not mention it again.

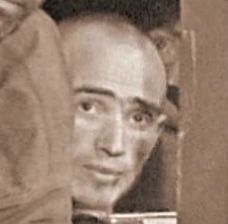

Left is a close-up of the boy Waltzer has maintained for several years is Elie Wiesel. Anyone can tell it is not and that’s why no one else ever publicly agreed with him.

I have some of what was on that site copied into articles here at EWCTW and also in my files. At left is the cropped section of the photo that Waltzer used on the banner of his MSU-Newsroom/Holocaust website that was very much dedicated to Elie Wiesel. (Another reader, Chris, informed me that he had found pages from the site using the Way Back Machine. Many thanks to him.) This shows that Waltzer definitely identified the boy in the black suit as Elie Wiesel. In addition, Jack Werber, a known dishonest survivor, was the supposed supplier of the picture.

I have some of what was on that site copied into articles here at EWCTW and also in my files. At left is the cropped section of the photo that Waltzer used on the banner of his MSU-Newsroom/Holocaust website that was very much dedicated to Elie Wiesel. (Another reader, Chris, informed me that he had found pages from the site using the Way Back Machine. Many thanks to him.) This shows that Waltzer definitely identified the boy in the black suit as Elie Wiesel. In addition, Jack Werber, a known dishonest survivor, was the supposed supplier of the picture.

Below right, a screen shot of one of the pages as it existed then, sent by a friend of EWCTW. It shows more of the emphasis on Elie Wiesel.

When I pointed out much of this in a podcast of March 25th, Waltzer sent me an email on March 28th stating,

My websites at UM FLint are down because I was appointed there one year and am now back at Michigan State.

Of course I never mentioned UM Flint and never even saw his website there. I was speaking about his MSU website, which was titled something like Ken Waltzer’s “MSU Newsroom Special Report.” It was full of information about his projects and especially what he calls “the rescue operation of children at Buchenwald.” It was up on the Net since at least 2008 2, then suddenly disappeared, with not even cache pages to be found. Did Waltzer tell me a fib, or did he just read the podcast program description and misinterpret what it said about “taking down web pages?” By now, he will know what I mean and may answer.

I think it is very possible that he timed the take-down of his MSU “Newsroom” site with his one-year visiting professorship at UM Flint — putting up a temporary website there which he could take down when he left. This is a way of confusing the picture in order to distract as much as possible from his more recent decision to put more distance between himself and his prior (false) assertions about Elie Wiesel.

I think it is very possible that he timed the take-down of his MSU “Newsroom” site with his one-year visiting professorship at UM Flint — putting up a temporary website there which he could take down when he left. This is a way of confusing the picture in order to distract as much as possible from his more recent decision to put more distance between himself and his prior (false) assertions about Elie Wiesel.

His intention was and is clearly to deceive. The harm is caused to ordinary people who believe and trust that they are getting knowledgeable answers from a professor of history and a holocaust scholar. In this particular case, all five of the elements necessary to prove fraud are there.

First, he sets up a University-sponsored website maintaining falsely that Elie Wiesel is the boy in the photograph of youthful “survivors” marching out of the camp (1). He knows it is false because he has no evidence or proof, only his own “wishful thinking.” The USHMM never identified Wiesel in that group of boys, nor did anyone else (including Wiesel himself), unless they did so from following Waltzer’s example (2). Waltzer’s intent was to make the public believe something that was not true – that he had proof of Elie Wiesel being one of the “rescued children” (3). Because Waltzer is a Professor of History and “holocaust expert” at a major university, and is at all times written up very favorably in the media, the public (you and I ) and his students will rely on his statements (4). These same students and public are injured when photographs are mislabled in order to foist on them a certain belief about an influential historical event that affects their entire world view (5).

* * *

This is just one instance of the untruths that Ken Waltzer has told over the years. Another tactic he uses is to promise an upcoming answer to your doubts which he cannot or does not produce now. As we have seen, we continue to wait as he continues to promise. Still another tactic is to accuse others of lying when it is he who is doing so. But only people who are knowledgeable enough about these complex and purposely obscured issues can see who is doing the lying. In this same email, Waltzer wrote:

The book is on track, and I have also completed a separate essay to be published on Elie Wiesel and Buchenwald.

Completed, he says. And separate. Why separate? I wrote back to him asking where I could find his essay because I wanted to read it. No reply – which is typical because factual information is not his forte, emotional rhetoric is. I feel it’s quite possible, even probable, he wrote a separate essay on Elie Wiesel so as not to tarnish his book with the false “facts” about Wiesel in Buchenwald. He can always get rid of an essay, if necessary, later – but not his entire book. What might there be in this essay? [As it turned out, the book never manifested at all –cy, 4-14-25] Will it be the same or quite different from what he wrote in a March 6, 2010 comment at Scrapbookpages Blog, when he said [my underlining-cy]:

For the skeptics [I was using the screen name “skeptic” then, at Scrapbook blog -cy] and know-nothings who have written in suggesting Eli Wiesel was not in the camps, that Night is purely fiction, you are all dead wrong. The Red Cross International Tracing Service Archives documents for Lazar Wiesel and his father prove beyond any doubt that Lazar and his father arrived from Buna to Buchenwald January 26, 1945, that his father soon died a few days later, and that Lazar Wiesel was then moved to block 66, the children’s block in the little camp in Buchenwald. THese documents are backed up by military interviews with others from Sighet who were also in block 66, and by the list of Buchenwald boys sent thereafter to France. All of this is public domain.

Wishful thinking by Holocaust deniers will not make their fantasies true. While Wiesel took liberties in writing Night as a literary masterpiece, Night is rooted in the foundation of Wiesel’s experience in the camps. The Buchenwald experience, particularly, runs closely to what is related in Night.

Comment by kenwaltzer — November 14, 2010 @ 6:57 am

How much untruth is contained in this, in order to defraud us all in his devoted service to the “Holocaust Industry” and the state of Israel? Plenty. As proof that Elie Wiesel was in Buchenwald, he points to documents for Lazar Wiesel and “his father.” It is even more absurd because Lazar Wiesel’s relative was only 13 years older than Lazar – it was in fact his brother Abram! Waltzer is passing off Lazar for Elie simply on the basis that Lazar also came from Sighet, Elie’s hometown and carries the same name. Sighet was a city of 50,000 or so with a very large Jewish population, and Wiesel was a common name. But the “scholar” who has taken years to research this and still isn’t finished, wants us to believe there can be only one Lazar Wiesel, who is Elie. He attributes the difference in their birthdates to bureaucratic error.

Previously I may have called this stupidity, but now I’m calling it fraud, based on the above-given definition. Of course Waltzer can see the discrepancies here, but he hopes he can convince you not to see them. The Military Interview mentioned with Lázár Wiesel’s name on it also does not have the right birthdate for Elie Wiesel, nor does the signature match Elie’s well-known signature.

Will Waltzer repeat this nonsense in his latest “completed” essay? Notice that Waltzer never fails in the name-calling department, here calling his critics names such as “know-nothings” and “Holocaust deniers.” Several months later, he wrote a similar comment at EWCTW to the blockbuster article: “Signatures Prove Lázár Wiesel is not Elie Wiesel”

by kenwaltzer

On November 14, 2010 at 10:34 am

Contrary to Carolyn Yeager’s wishful thinking, Eli Wiesel was indeed the Lazar Wiesel who was admitted to Buchenwald on January 26, 1945, who was subsequently shifted to block 66, and who was interviewed by military authorities before being permitted to leave Buchenwald to go with other Buchenwald orphans to France. Furthermore, there is not a shadow of a doubt about this, although the Buchenwald records do erroneously contain — on some pieces — the birth date of 1913 rather than 1928. A forthcoming paper resolves the “riddle of Lazar” and indicates that Miklos Gruner’s Stolen Identity is a set of false charges and attack on Wiesel without any foundation.

The promise of a forthcoming paper turned out to be a fib. From Nov. 2010 to now, there has not been any paper. Maybe it’s the essay he mentioned in his March 28th email? “Forthcoming” to Waltzer means up to two and a half years, it seems. That in itself is the sign of an unreliable person.

There can be only one reason Ken Waltzer allows himself to look like a buffoon and a shyster. He doesn’t need to do it to keep his position at Michigan State University. He does it because it is his larger job to keep the Buchenwald atrocity stories and Liberation lies, including the Elie Wiesel myth, alive and well in the mind of the public. He works for purely Jewish interests – I will be writing a future article on the priority, meaning and funding of Jewish Studies programs in American universities. For now, I can add that Waltzer is more of a public relations (PR) worker for the Holocaust Industry, the State of Israel and maybe AIPAC, than he is an honest-to-god academic. Another organization connected to Israel that he serves is Scholars for Peace in the Middle East. He has written four attack-dog articles for them since 2009, functioning in a sort of Abe Foxman-pitbull style.

In Nov. 2009, he attacked Alison Wier as another “know-nothing” because she speaks up for Palestinian rights on college campuses, where she is popular.

In May 2010, he went after John Mearsheimer for calling Israel “an apartheid state” and also took out after Noam Chomsky, Norman Finkelstein, and “the crackpot Phil Weiss.”

Also in May 2010, another target was Judith Butler, who campaigned at the Berkeley campus for the university “to divest from companies making military weapons which Israel employs to commit war crimes.”

In August 2011, he wrote on the Israeli-Palestinian peace process, arguing for Israel’s interests to be well and strongly presented on college campuses.

But this is only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to Walzer’s pro-Israel activities. I will be writing further articles that present the evidence for Ken Waltzer being guilty of fraud in his public writings and during his entire career. Much of it revolves around Elie Wiesel and the Industry’s need to place him at Buchenwald. My position, if you have somehow missed it, is that Elie Wiesel was never at Buchenwald. I am also saying that Waltzer is backing down or “stepping back” from his blatant, dishonest claims about Wiesel, but he can’t back down altogether.

Endnotes:

1. I have also seen it dated April 27 at the USHMM and have used that date in other articles here. Now I have only found this one picture which is very officially dated the 17th. There may have been an attempt to move the date to the 27th so that Wiesel could be in the picture (though he supposedly would not have been released from the hospital until the 28th). It is really too bad the USHMM cannot be relied upon; nor can Yad Vashem. When the museum “researchers” are involved in lying or in complacency, one really has nowhere to turn.

2. http://msutoday.msu.edu/news/2008/mapping-the-holocaust-archive-msu-prof-explores-records-of-nazi-atrocities At bottom of article, it reads “For more information, and to follow Waltzer’s research and read his journal as he participates in the workshop, visit the special report at: http://special.newsroom.msu.edu/holocaust.” This is a link to the website that no longer exists, as you will see if you click it. Now he seems to be pretending it was never there.

11 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: Abram Vizel, Buchenwald camp, Buchenwald liberation, Elie Wiesel, Holocaust Industry, Israel, Ken Waltzer, Lazar Wiesel, legal definition of fraud, M. Grüner, Michigan State University, Night, Scholars for Peace in the MIddle East, USHMM,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Saturday, May 19th, 2012

by Carolyn Yeager

To cry or not to cry, that is the question.

Elie Wiesel, as usual, cannot make up his mind.

On May 6, he gave a major speech (for big bucks) at Xavier University in Cincinnati, brought there by the Center for Holocaust and Humanity Education. A reporter who covered the speech wrote that Wiesel said this:

Wiesel recounted his rescue from the concentration camp by the U.S. Army and said he remains grateful.

“We cried,” he recalled. “We discovered for the first time that we could cry.”

But in an interview that was published on the following day, May 7, on NBC New York, Wiesel said the opposite to reporter Gabe Pressman:

He told me about the day the American army came to liberate the prisoners,

How the prisoners “wanted to cry but they didn’t know how to cry… if you cry, you will never stop so they didn’t even do that.”

So which is it? Did they cry or didn’t they? It seems you get to choose which version you like best.

I pointed out in this article on the Xavier speech that this was the first time I had ever heard or read Elie Wiesel say that he or his barracks-mates cried. Since this Blog takes the position that Wiesel was not even there (in Buchenwald), it’s kind of a mute point–except for the fact that it’s one more reason not to believe he was there. He can’t keep his “story” about it straight.

Wiesel embellished his Buchenwald liberation tale when he was interviewed by Oprah Winfrey, too. As I recounted in this article, he told Oprah in Nov. 2000 that the first thing the religious boys in his barracks did was to “reassemble” and offer prayers for the dead–yet in his books he made a point to say the only thing anyone did was go after the food provisions. He wrote that they had no thought of their families nor of friends, only of food.

The flexibility of memory

Considering all this, we arrive at a crucial question about the Holocaust. The fate of nations may hang on it! What does it mean if Memory, that sacred human ability on which the entire holocaust narrative rests, cannot be depended upon?

Elie Wiesel’s memory is clearly not reliable. Yet he himself has made everything depend on memory. He wrote: “I shall never forget that night, the first night in camp […] never shall I forget those moments … ” and so on. But he must have forgotten some things since his story doesn’t remain consistent.

Memory itself–the act of remembrance–is just not what Elie Wiesel makes it out to be. For Weisel, it’s more like these words he is famous for saying: Some things are true though they didn’t happen, while others are not, even if they did. That is how we tend to remember!

In his case, Elie Wiesel was liberated from Buchenwald, even if he wasn’t … and it’s not true that the prisoners were only interested in food, even if they were. Memory–it’s such a flexible thing.

17 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: Buchenwald liberation, Elie Wiesel, Holocaust fraud, memory, Oprah Winfrey,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Thursday, November 24th, 2011

In January, I featured a “Letter of the Week” and said when we got another letter as good as Hailey’s, or almost as good, I would feature it in the same way. Well, Elie Wiesel Cons The World recently received two comments, spaced 2 days apart, that are almost as good as the letter from haileylovespink.

I’m replying to both of them here. On Nov. 20 Shelby commented on my article Gigantic Fraud Carried out for Wiesel Nobel Prize. She wrote:

I’m replying to both of them here. On Nov. 20 Shelby commented on my article Gigantic Fraud Carried out for Wiesel Nobel Prize. She wrote:

Really people so what he lied about a picture he was still there. Leave him alone. He has been through more in his life than you can ever imagine. So leave it be. Don’t ruin the rest of a mans life cause you are unsatisfied with yours.

This wording has a familiar ring to it, but I won’t speculate about who it might be and just accept it as is. Shelby, you seem to be admitting Wiesel lied about being in the picture (famous Buchenwald liberation photograph), yet you are still sure he was there. Are you fantasizing? Without evidence, you cannot say for sure he was there just because its been assumed all these years.

You also call lying about being in the picture a “so what.” Shelby, it’s not “so what.” This is not just any picture. It happens to be the only “proof” that he was there. Further, it reveals a serious moral failure. Elie Wiesel knows whether he’s in that picture or not; he himself cannot be fooled about it. So you are right, he lied. He lied in order to get a Nobel Prize.

As to what Wiesel “has been through” in his life, he was, according to him, in German custody for one year, from May 1944 to April 1945 … after that, he had everything good done for him. One bad year out of 83 years in all … I’m sure many people would be happy to trade that with him. So your sympathy for someone you don’t know (or do you?), and don’t really know anything about, is wasted and even foolish. As to me being dissatisfied with my own life … well, you don’t know that, do you? I’m happy to report to you that is not the case.

On Nov. 22, Sarah wrote a longer comment about my article New Evidence on Elie Wiesel at Buchenwald. She writes:

this website is truly disgusting, so what if Elie isn’t documented properly within the records, you do realize Nazi’s didn’t bother documenting EVERY SINGLE PERSON to go through each camp, they could care less. Not all records will be accurate, and regardless if Elie did live in Buchenwald or not makes no difference, but why a man who has suffered and endured so much, lie about where he’s been, for every historian or writer who thinks any holocaust survivor is lying about their experinces cannot speak on their behalf because they have not been in same position.

Sarah, you also say “so what” … so what if Wiesel isn’t documented, makes no difference to you. In fact, it even makes no difference whether Elie ever lived in Buchenwald. But if Elie didn’t live in Buchenwald, his entire story is false, Sarah. Can’t you understand that? You are a real believer.

What does make a difference to you appears to be that those who are not holocaust survivors have not been in the same position … therefore we cannot accuse the survivors of lying. Sarah, just like Elie, you fall back on the position that “holocaust survivors” are beyond the understanding, and therefore the criticism, of we ordinary mortals. That is holocaustianity–a belief–not history or science. The doctrine of holocaustianity is: Don’t ask questions; those who ask questions are disgusting unbelievers.

I invite Shelby and Sarah to write again; they are always welcome here. In the meantime, here is an idea for them to consider: Get Mr. Wiesel to show all of us his tattoo that he claims to have on his arm and that will go a long way toward shutting us up.

Update: replies from Sarah and Carolyn

On November 24, 2011 Sarah replied to the above:

Glad you were able to reply back Carolyn, I assumed you would be busy writing more articles on Elie Wisel lying to the public about his experiences. I have read more articles on your website, and you might be surprised to hear that I have a slight change in opinion, yes the tattoo not being where it should be is very strange, but I still don’t believe that calling this man a con is the right way to go about it and yes he could be lying about his experiences, but reading his novels, can you honestly tell me that someone can make all of that up? Can you tell me that you could write a novel like Night, lie about such a tragic experience such as the Holocaust. As I read further on in your articles it disgusts me to see that the many people who comment don’t believe the holocaust ever happened. This is quite ironic actually, Carolyn, you have evidence to prove that Elie Wisel is lying about his time in the concentration camps, and the proof you have is quite substantial, so how is it that with the proof that British soldiers brought from Bergen-Belsen and the numerous photos taken of the prisoners shown to the general public are disregarded and hundreds of testimonies from real survivors are just tossed aside(unless you are going to go on to prove every single survivor is lying and find proof to back that up). In my opinion, that’s real evidence, and yet people continue to deny the holocaust, and your site seems to support that as well, funny, isn’t it. I guess for most people, the truth is hard to swallow, and its easier to deny that millions of people died under the watch of the entire world and nothing was done for years; rather than accept that an entire race was almost abolished because of pure ignorance. Hope to hear from you soon Carolyn, and I read Hailey’s post, and I love her for that, why do you spend so much time trying to prove 1 man wrong, regardless if he’s never even set foot on a camp soil, the Nazi’s had a final plan to kill all Jews, they almost accomplished just that, the Allies took their sweet time getting to these camps and what do people says years later? “It’s a lie, Jewish people just want to hype up German hatred.” “Its all a Holohoax.”

It’s great to see what kind of world we live in………so far I don’t see any sites denying the Rwanda Genocide, so is that what’s next, worldwide denial of that, or can we just refer to all the videos of the dead bodies along the road…..OH WAIT, didn’t we see that in the concentration camps?

On November 25, 2011 Carolyn replied to Sarah:

I welcome the opportunity to discuss with you all that you have brought up. But first I have to chide you for changing the subject. You gave up on defending Elie Wiesel very quickly, but you still don’t want to admit he lies. You admit the tattoo is not where it should be but you leave out that he says it is there. Doesn’t this alone make him something of a con man? What else would you call it? A liar? A mental case? A person who thinks he is above all rules and/or physical laws? Please explain to me why he would say he has an A-7713 tattoo on his arm when the rest of the world can see that he doesn’t. I’ll give you a hint: he is very ambitious; and he knows the Media will never bring it up, will never ask him about it. He knows the all-powerful Media is in the hands of His Friends.

You bring up his novels. How many of his novels have you read? Only Night? You ask if I could write such a novel without being in the camps. The answer is yes because others have done it; quite a few fraudulent concentration camp stories have been uncovered. Almost all holocaust survivor books are half fiction. There is so much literature about the camps out there, all you have to do is read it and then write your own. Also, Night has many un-credible and inaccurate passages (some even copied on the sidebar of this website) that have caused critics to question whether Wiesel was actually there — long before Myklos Grüner came on the scene with documents. In all sincerity, Sarah, I don’t think you could defend the book Night if you had to.

At this point you jump to Bergen-Belsen, since you have not made your case about Wiesel. This is what holocaust believers invariably do. But this website is only about Elie Wiesel. I stick to that so people can’t change the subject on me and go around in circles as you’re doing. It’s clear to me that you realize Elie Wiesel cannot be defended, as many are coming to realize, but you don’t want to talk about it. You say calling Wiesel a con is not the right way to go about it; that yes, he may be lying but his book is so good. This does not make sense. He is or he isn’t. The facts say he is, which you recognize.

You only sound silly, Sarah, because you’re trying to defend the indefensible. So you say to me: “why do you spend so much time trying to prove 1 man wrong, regardless if he’s never even set foot on a camp soil, the Nazi’s had a final plan to kill all Jews, they almost accomplished just that …” If the Nazi’s had such a plan (which has never been discovered) they certainly didn’t come close to killing all Jews. There were more Jews than ever shortly after the war, moving and emigrating all over the world. Real statistics prove it. The world has no shortage of Jews. But to get back to Elie Wiesel, do you admit he is a fraud? Are you really going to argue that whether he is or isn’t, he should be left alone and remain the icon of the Holocaust? Are you that comfortable with dishonesty? Should the Holocaust stand on fraud? These are serious questions you and all Jews should consider.

Further replies follow in the Comments section below.

6 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: Buchenwald liberation, Elie Wiesel, holocaustianity,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Monday, September 12th, 2011

By Carolyn Yeager

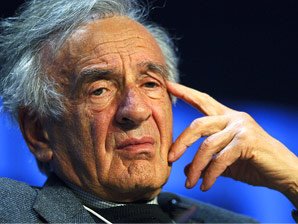

Proof that the man in the famous Buchenwald photograph is NOT Elie Wiesel.

With the help of the New York Times and the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, Elie Wiesel and his backers did not shy away from criminal deceit by purposely misidentifying an unknown face in this famous photo as belonging to Elie Wiesel.

The above high-resolution photograph of Buchenwald survivors was first published in the New York Times on May 6, 1945 with the caption “Crowded Bunks in the Prison Camp at Buchenwald”. [click on image twice to enlarge fully] It was taken inside Block #56 by Private H. Miller of the Civil Affairs Branch of the U.S. Army Signal Corps on April 16, 1945, five days after the Buchenwald camp was liberated by a division of the US Third Army on April 11, 1945. None of the men in the picture were identified at that time.

The U.S. Army photographer was in block #56, not #66

The U.S. Army photographer said he was inside Block #56. The “children’s block” that housed the so-called “boys of Buchenwald” was #66. This was not a typo. Note that these men are not children or teenagers, except for the youngster on the lower left who has been correctly identified as 16 yr. old Myklos (Nikolaus) Grüner, and maybe a couple others. These adults appear to be a mixture of sick individuals suffering from a wasting disease (Grüner learned after liberation he had TB), along with basically healthy men who were also in that block, for some unknown reason, five days after they had been freed. As we have read from many Buchenwald inmates, they moved about at will from the day of liberation onward. In Elie Wiesel’s book Night, he even says that some of the boys in his block went to the city of Weimar the very next day to steal potatoes and rape girls.

The true facts of this photograph have never been told and perhaps are not known. (Grüner has written in Stolen Identity that he left a procession of youths being led to the camp entrance on the morning of April 11, scurried into the nearest barracks and jumped into an empty bunk space. It turned out to be this one.) But because of the man standing there stark naked except for a piece of clothing held in his hands to cover himself, this photograph was certainly staged. In any event, it was never represented as the “children’s barracks.” Still, Elie Wiesel inexplicably once told an interviewer for the German weekly Die Zeit that this photograph was taken in the Children’s Block and all these men were really teenagers even though they looked old. (Source: “1945 und Heute: Holocaust,” Die Zeit, April 21, 1995.)

Kenneth Waltzer wrote to this website EWCTW on Nov. 14, 2010: “Eli Wiesel was indeed the Lazar Wiesel who was admitted to Buchenwald on January 26, 1945, who was subsequently shifted to block 66…” and Waltzer repeated in another comment on June 27, 2011 that “— after his father died — Elie Wiesel was moved in early February to block 66, the kinderblock. Miklos Gruner too was in block 66. Elie Wiesel was there with other boys from Sighet, who knew him.”

But we are also to accept that on April 16 Wiesel was in block 56, even though he didn’t report any such move in his book Night. In fact, in that fictitious story, Wiesel says he became deathly ill with food poisoning three days after liberation (April 14) and spent the next two weeks in hospital (pg 115, Marion Wiesel translation). That in itself precludes his being in this photograph taken on April 16!

Whom do you believe—the New York Times or your own eyes?

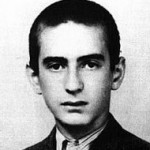

Not Wiesel at age 16 in 1945

Not Wiesel at age 16 in 1945

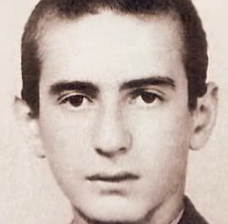

You can see for yourself from these two high-quality photographs supplied to me by a helpful reader that the face on the left is not Wiesel. A close inspection of the prisoners in the bunks in the famous photograph reveals that the eyebrows on many (including the one on the left above) were emphasized with a dark crayon/pencil … in other words, retouched or “photo-shopped.” On the right is what is claimed to be Elie Wiesel in 1944 at the age of 15.

The inmate on the left definitely has an aquiline nose and full, even sensual, lips. In this close-up, the receding hairline is visible on the recently shaved head. On the right, the real 15-year-old Elie Wiesel exhibits a normal youthful hairline, a bigger and longer nose and thinner lips. He also has a higher forehead and longer face than the more roundish-headed inmate. The eyes of the man on the left are not as deep-set under the eyebrows. His somewhat surprised, curious expression is not typical of Wiesel, whose expression was generally reserved, and often hooded.

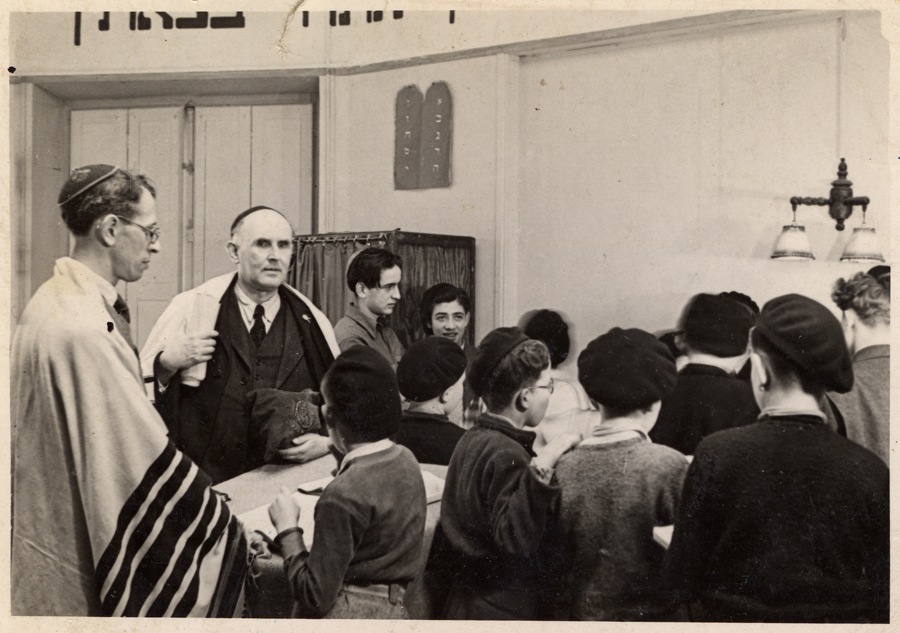

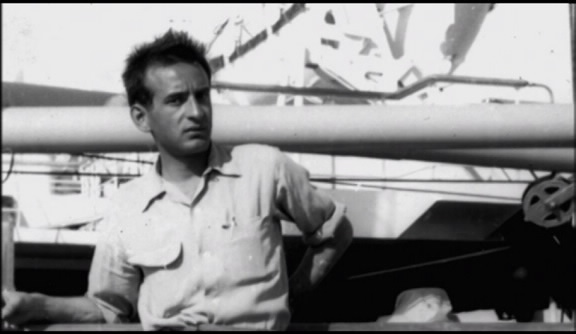

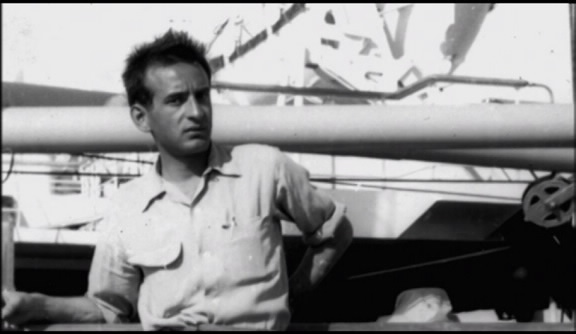

The close-up on the left appears to be the real Elie Wiesel in France later in 1945. He would be 17 or almost 17 years old in this picture. Notice the non-receding, youthful hairline with a very long front lock hanging to the side, and the straight nose .

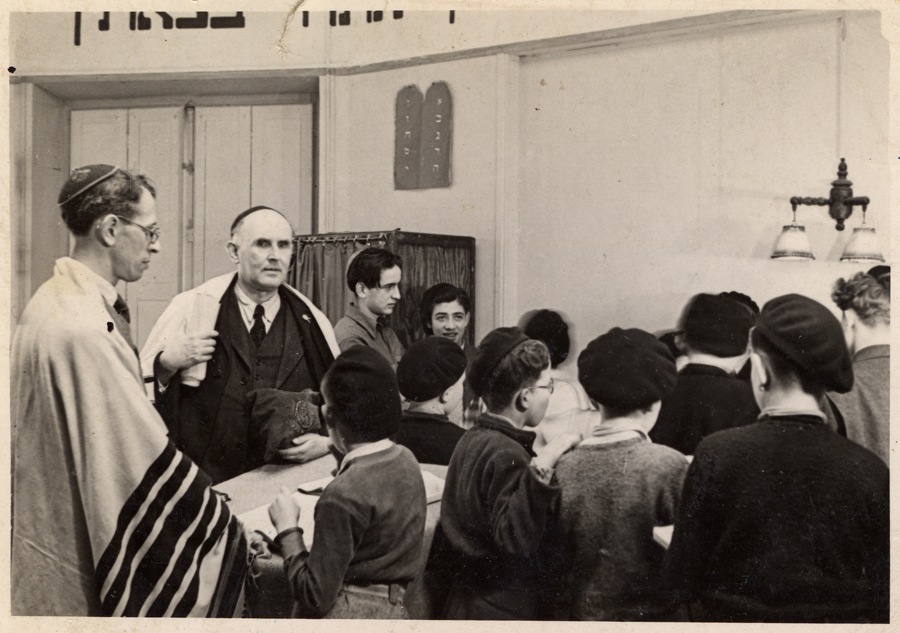

This close-up image is from the photograph below, which is found at the USHMM Survivor Resource Center with the caption given below. (click here or on lower pic for an undistorted, larger image)

Above, Jewish boys gather for a prayer service in a chapel in an OSE children’s home in 1945. Those pictured include Elie Wiesel (seen in profile) and Jakob Rybsztajn standing next to him facing the camera. (I note that Elie Wiesel is older than the other boys in this picture, giving support to the idea that he acted in the role of counselor and sometime teacher to the newer, younger religious boys.)

Notice again the straight nose, the high forehead, deep-set eyes, large ears, sensitive mouth and slender neck. But also look at all that hair! The date of this picture is given by USHMM as 1945 and the location as Ambloy, [Loir et Cher] France. It says in the accompanying text “In October 1945 the children and staff of Ambloy were relocated to the Chateau de Vaucelles in Taverny (Val d’Oise).” That means this picture was taken between June and October 1945. They could have been celebrating Rosh Hashana, Yom Kippur or Sukkot.

But could his hair have grown to such a length from a shaved head in April 1945? No way, and thus we have another proof that the liberated Buchenwald inmate with the shaved head is NOT Elie Wiesel.

A PDF from my valued contributer examines the ages of the small group more closely. In my opinion, he has the ages of all four men a little too young but especially #2 and 4. Take a look: four men in bunk

Who first identified Elie Wiesel in the famous Buchenwald liberation photo?

In October 1983 the Jewish-owned New York Times published this photograph as part of an article in its high circulation Sunday NYT Magazine with the caption: “On April 11, 1945, American troops liberated the concentration camp’s survivors, including Elie, who later identified himself as the man circled in the photo.”

It was also in 1983 that Wiesel’s friend Sigmund Strochlitz began campaigning for a Nobel prize for Wiesel. Letters of nomination are due into the Nobel committee by Feb.1 of each year, so by January 1984, the committee was receiving letters nominating Wiesel from U.S. Senators such as Daniel Moynihan and Barry Goldwater (both Jewish). [see “How Elie Wiesel Got the Nobel Peace Prize“] The effort continued, with new and ever more innovative ideas, through 1985 and 1986 with the help of Jew John Silber, President of Boston University, Wiesel’s employer. Hundreds were enlisted into the effort.

The 1983 article in the New York Times that was the opening gun of the campaign was written by Jew Samuel Freedman and titled “Bearing Witness: The Life and Work of Elie Wiesel.” It included this line: “His name has been frequently mentioned as a possible recipient of a Nobel Prize, for either peace or literature.” Well, it had just begun to be mentioned … by this team of cheerleaders.

Wiesel pretends that he had nothing to do with it. In an interview in France in 2009, he said: “If you fight or if you do scientific research to get the Nobel, you never succeed and you should not succeed.” (Elie Wiesel, “messager de la memoire”) No, he did not fight but his mercenaries fought for him, and he used this photograph as his “research.” That this photograph played a large role is shown by the fact that immediately after the Nobel award ceremony in December 1986, Wiesel went to Yad Vashem Memorial in Jerusalem and posed in front of its prominent display there.

Elie Wiesel on Dec. 18, 1986 at Yad Vashem in Jerusalem

After the award was announced by the Nobel Committee, the New York Times published on Nov. 1 a severely cropped version of the Buchenwald photo (below) with the caption: “Elie Wiesel, the winner of the Nobel Peace Prize (at far right in the top bunk) in the Buchenwald concentration camp in April 1945, when the camp was liberated by American troops.” The picture accompanied an article by Jew Martin Susskind titled, “A Voice from Bonn: History Cannot Be Shrugged Off.”

The role played by the tax-payer funded United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Elie Wiesel finagled his way to becoming Founding Chairman of the United States Holocaust Memorial Council in 1980 after being chosen in 1978 by President Jimmy Carter as chairman of the President’s Commission on the Holocaust. Why the United States needed to do anything at all about the “Holocaust” is something only the 2.5% Jewish population in this country can answer. It is to satisfy them. Wiesel continued to chair the Council until 1986, when he reached his goal of becoming a Nobel Laureate. The USHMM was undoubtedly an important institutional heavyweight that leveraged him to the Nobel.

The USHMM naturally accepted that Wiesel was in the famous photograph as soon as he and the New York Times said he was. If you think the museum staff does real research, is searching for truth and/or is engaged in scholarship of any kind, you are badly mistaken. The museum represents official power only and is invested in keeping it in Jewish hands.

This photograph is the only document tying Elie Wiesel to the Holocaust

The only document that connects Elie Wiesel to the Auschwitz-Birkenau and Buchenwald experience he claims to have—in other words, his claim to be an authentic “Holocaust survivor”—is the famous Buchenwald liberation photograph. There are no records with his name and birth date for either camp. His books do not support his presence there very well. That’s why the Wiesel promoters, who wanted to anchor their man’s claim to be the unchallenged spokesman for the world’s greatest victims—which winning a Nobel prize would surely do—decided that they could pawn that unknown face off as the face of Wiesel. This decision was made in 1983. It’s certain that Elie Wiesel took part in making it, though the pretense is kept up by all that he was aloof from the entire process.

What you must do

When you comprehend the immense power that this simple photo comparison and commentary gives us, you know that we have it in our hands to break down the Wiesel legend if this knowledge is widely circulated. If you understand this, you know what you must do. You must post this article everywhere you can, you must tell everyone about it, send it to all you know … make sure that this photo comparison moves through the Internet and finds a home in as many places as possible. And keep it up, because once is not enough. I’ve done my part, readers. Now it’s up to you.

54 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: Ambloy France, Block 66, boys of Buchenwald, Buchenwald liberation, Elie Wiesel, Holocaust fraud, Ken Waltzer, Myklos Gruener, New York Times, Nobel Peace Prize, OSE, US Holocaust Memorial Museum, USHMM,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Sunday, December 5th, 2010

By Carolyn Yeager

More reasons why I don’t believe Elie Wiesel is the author of Un di Velt Hot Gesvign

A dear reader has brought to my attention something that I covered in “The Shadowy Origins of Night, I, II and III”, but which deserves revisiting in order to shine a brighter light on some perhaps small, but meaningful, details that impact on the question of whether Elie Wiesel is the author of the Yiddish-language Un di Velt Hot Gesvign (And the World Remained Silent).

If we start with the map provided in “Shadowy Origins of Night, Part II,” we notice that Sighet is not in Transylvania, but in Maramures [sometimes called Marmaros], a district distinct from Transylvania. We see that Sighet is the only city shown in the eastern half of Maramures and is exactly on the border with Czechoslovakia.

The writer of Un di Velt describes his hometown of Sighet on the first page of the book as

the most important city [shtot] and the one with the largest Jewish population in the province of Marmarosh. Until the First World War, Sighet belonged to Austro-Hungary. Then it became part of Romania. In 1940, Hungary acquired it again.” 1

It is totally reasonable for a man born in 1913, as was Lazar Wiesel, to write such a description since, at the time of his birth, Sighet was indeed part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. After WWI [1919] it became part of Romania when the borders of Central and Eastern Europe were “rearranged” by the victorious powers [France, Britain, United States]. Then, in 1940, at his age of 27, it again changed rulers and borders, and became German-allied Hungary.

Lazar Wiesel lived through all these changes. He was old enough to understand them. As a man in his thirties at the end of the war, and his early forties when the book was published in 1955, Lazar Wiesel could be expected to write a comprehensive account of his experience—not only a good deal of historical/political material on his hometown and its townspeople, but covering his personal political/religious beliefs also. And this is indeed what we know is contained in the published book, Un di Velt. 2 Taking eight to nine years to complete the entire 862 pages of it, if that’s what it was, is quite reasonable, and even to be expected.

This makes a great deal more sense than Elie Wiesel’s incredible description of frantically typing 862 pages of “memory” during an ocean voyage to Brazil, without pre-planning, reference materials or access to other persons.

Returning to the location of Sighet, Wiesel, in the French and English versions La Nuit and Night, changed, on the first page, what had been described as the “most important city with the largest Jewish population in the Maramures province” to:

that little town in Transylvania where I spent my childhood.

Nothing more. Why does Elie Wiesel say that Sighet was in Transylvania? Could it be because the average person might recognize that name in association with Hungary and/or Romania, while they would not recognize Maramures or Marmarosh? And why would the author’s hometown go from the largest city in the entire province to a little town, presumably of no significance?

While it is true that more recently Maramureş, Romanian Crişana and the Romanian Banat are sometimes considered part of Transylvania, it is not precisely so. An inhabitant who identified with his region would probably not put it that way, but someone for whom the geography held no special place in his mind, heart or memory, this kind of generalization might be preferred. For example, if I don’t want a person[s] to know much about me or ask me questions, I will say I was born in the American mid-west and hope to leave it at that. If I don’t mind more being known, I’ll say exactly where, and give some detail. I know, because I do both and it’s very clear to me why.

Whatever the reasons Elie Wiesel had to cloud the picture of his hometown, it is clear that he and his publisher wanted to emphasize some things, de-emphasize, or delete, others, and shorten, shorten, shorten. This fictionalizes the account.

For me, the crux of whether to accept Elie Wiesel as the author of Un di Velt comes down to that odd paragraph in his 1995 memoir3 describing the burst of unbelievable energy that came over him while on a ship traveling between France and Brazil, when he typed 862 pages of 9 year-old memories on a portable Yiddish typewriter within no more than a two week time period.. Think back nine years in your own life and discover just how clearly you can remember everything that took place. Yes, his was an exceptionally traumatic time, but that doesn’t necessarily make one’s memories any clearer, just that certain parts stand out from the rest. Also, for me as a writer, just that high amount of sustained, concentrated typing would be an impossible task.

Another difficulty is that Wiesel didn’t describe the writing of his original manuscript until it appeared in his memoir, where, as I continue to remind, he gave it only one short paragraph! Or, if you will, a few sentences. I said above that it is a lot to swallow. I want to make it plain right now that I cannot, and thus do not, swallow it. I am convinced Elie Wiesel did not write Un di Velt Hot Gesvign [And the World Remained Silent]. I think it remains for him to prove that he did so, since his attempts at that so far only make us doubt it the more. He can begin by answering some of the many questions put to him on this website, as they are not frivolous or unfair.

In the remainder of this article, I will point to further items of interest and fact that, while not individually conclusive, bolster my position “not to believe.”

Night is a work of fiction

We must remember that Night was classified as fiction when it was first published. Today, there is a good deal of embarrassed uncertainty as to how to categorize it. The original English-language Hill and Wang publication in 1960 listed the book as Judaica/Literature. The new translation from the same publisher issued in 2006 says it is Autobiography/Jewish Interest. On the Wikipedia page for Night,4 it is called “Autobiography, memoir, novel”—all three. Words lose their meaning when dealing with Elie Wiesel, and we’re familiar with his professed difficulty with “the limitations of language.”

On that same Wikipedia page, we read:

[I]t remains unclear how much of Wiesel’s story is memoir. He has reacted angrily to the idea that any of it is fiction, calling it his deposition, but scholars have nevertheless had difficulty approaching it as an unvarnished account.

Most who write about Wiesel are not scholars or, if they claim to be, they don’t live up to the title. Ruth Franklin, though an avid apologist for Wiesel, admits that the original Yiddish author blames the Jewish concept of “chosenness” as the source of the Jews’ troubles, and she accepts that Wiesel is the author.5 Yet this is an idea that Wiesel would never entertain for an instant. Franklin writes:

The Yiddish version was an historical work, political and angry, blaming the Jewish concept of chosenness as the source of the Jews’ troubles. Wiesel wrote in the 1956 Yiddish version: “In the beginning was belief, foolish belief, and faith, empty faith, and illusion, the terrible illusion. … We believed in God, had faith in man, and lived with the illusion that in each one of us is a sacred spark from the fire of the shekinah, that each one carried in his eyes and in his soul the sign of God. This was the source—if not the cause—of all our misfortune.

Naomi Seidman, professor of Jewish culture at the Graduate Theological Union, whose article 6 I have referred to above and quoted in “Shadowy Origins,” documented the transition from a historical account of events to an autobiographical novel, concluding that Night transforms the Holocaust into a religious event, the abdication of God, with the witness [Eliezer] both priest and prophet. Wiesel himself has said that Auschwitz is as important as Mount Sinai—where in the Bible the Ten Commandments were given to Moses by God.7

On the Internet, we find various sites that still call Night a novel. At the website About.com: Secondary Education, Night is called “A novel by Elie Wiesel.”

At the website Yahoo!Answers, the question is asked: Discuss the significance of “night” in the novel Night by Elie Wiesel?

In 2006, Alexander Cockburn wrote 8:

Amazon.com […] had been categorizing the new edition of Night under “fiction and literature” but, under the categorical imperative of Kakutani’s “memory as a sacred act”9 or a phone call from Wiesel’s publisher, hastily switched it to “biography and memoir”. Within hours it had reached number 3 on Amazon’s bestseller list. That same evening, January 17, Night topped both the “biography” and “fiction” bestseller lists on BarnesandNoble.com.

In the same article, Cockburn tells of an interview with Eli Pfefferkorn of Toronto, who related this story:

“In 1981, Wiesel invited me to give a talk to his seminar students at Boston University. In the course of my talk, I discussed the relationship between memory and imagination in a number of literary works. I then pointed out the literary devices he used in Night, devices, I stressed, that make the memoir a compelling read. Wiesel’s reaction to my comments was swift as lightning. I had never seen him as angry before or since. In the presence of John Silber, the then President of Boston University, and my own Brown University students whom I invited, he lost his composure, lashing out at me for daring to question the literalness of the memoir. In Wiesel’s eyes, as in the eyes of his disciples, Night assumed a level of sacrosanctity, next in importance to the giving of the Torah at Mt. Sinai. In terms of veracity, it is a factually recorded work, virtually meeting Leopold von Ranke’s benchmark of historical accounts: Wie es eigentlich gewessen, how it really was.

Examples of fiction in Night

Beyond all the well-known fictions in Night, there are some that may have gone largely unnoticed. For example, another dear reader pointed out that on page 68 of the 1960 edition,10 a hanging is described as taking place at Buna [Monowitz].

The head of the camp began to read his verdict, hammering out each phrase:

“In the name of Himmler … prisoner Number … stole

[…]

prisoner Number …is condemned to death.”

The reader commented, “The person who wrote that could never have been around any SS officers. Heinrich Himmler was only referred to as Reichsfüher.” He further points to the fact that in the new 2006 translation of the book, the passage was changed [on page 62] to:

In the name of Reichsführer Himmler …

Someone obviously pointed out the error to Wiesel or his editors. But this doesn’t fix it either, because not even a lowly camp inmate would be sentenced to death in the name of the second in command. The order would have to read: In the name of the Führer …

Says my reader: This is enough in itself to prove that Wiesel had never been around any SS personnel.

There is another similar incident in Night that is widely considered to be fiction, in full or in part. This is the 3-person hanging scene, also known as the “Crucifixion” scene. It appears on page 70 in the 1960 edition:

One day when we came back from work, we saw three gallows rearing up in the assembly place, three black crows. Roll call. SS all round us, machine guns trained: the traditional ceremony. Three victims in chains—and one of them, the little servant, the sad-eyed angel.

The SS seemed more preoccupied, more disturbed than usual. To hang a young boy in front of thousands of spectators was no light matter. The head of the camp read the verdict. All eyes were on the child. He was lividly pale, almost calm, biting his lips. The gallows threw its shadow over him.

This time the Lagerkapo refused to act as executioner. Three SS replaced him.

The three victims mounted together onto the chairs.

The three necks were placed at the same moment with the nooses.

“Long live liberty!” cried the two adults.

But the child was silent.