Archive for the ‘Featured’ Category

Thursday, May 10th, 2012

By Carolyn Yeager

copyright 2012 carolyn yeager

The official Holocaust narrative versus Elie Wiesel on what is Auschwitz Liberation Day

The official Holocaust narrative has it that the Red Army did not arrive at the Auschwitz labor camps until January 27th, 1945—where they found some of the barracks burning, and also blown-up crematorium buildings which had housed “gas chambers.” This is the date that is commemorated all over the world as the Liberation of Auschwitz.

The official Holocaust narrative has it that the Red Army did not arrive at the Auschwitz labor camps until January 27th, 1945—where they found some of the barracks burning, and also blown-up crematorium buildings which had housed “gas chambers.” This is the date that is commemorated all over the world as the Liberation of Auschwitz.

However, on page 87 of the novel Night it is stated that the Russians “liberated” the inmates who were left behind at Monowitz (Auschwitz III) on January 20th, two days after the bulk of the prisoners left on the one-day forced march to Gleiwitz, from where they were put on a train to Buchenwald.

______________________

The photograph at right is a still photo from a Soviet propaganda film about the Auschwitz liberation. The clothing warehouses, known as “Canada,” are burning. But who set them on fire? [Author’s note: In January 2014, I wrote in an article published here: The photograph at right, a still from a Soviet propaganda film about the Auschwitz “liberation,” had been thought to be of the clothing warehouses burning. But new research suggests it is more likely regular barracks, probably in Compound B1. If this is true, it makes little difference when the picture was taken, as it was certainly after the Russians arrived.]

___________________________________________________________________________________

I included this detail in Night #1 and Night #2, Part Two under the heading “A record of fact it isn’t.” For the first time I’ve seen anywhere, I pointed out this sentence from Elie Wiesel’s book Night:

A strange detail … is on page 87 of the original Night. Eliezer remarks, after his and his Father’s deliberations and final decision to go on the march: “I learned after the war the fate of those who had stayed behind in the hospital. They were quite simply liberated by the Russians two days after the evacuation.” The evacuation, as we all know, was on the 18th. We also know the Russians did not arrive on the 20th of January! The actual liberation day is January 27. What possessed Wiesel to write this? Well, because it was in Un di velt: “Two days after we had left Buna, the Red Army occupied the camp. All the sick had stayed alive.”

It’s important to keep in mind that the Jan. 20th liberation originally appeared in Un di velt hot geshvign, the Yiddish book published in 1955 from which La Nuit was born in 1958 (with the English version Night following in 1960). Whether or not Elie Wiesel is the author of the Yiddish book, there is no doubt that he wrote La Nuit directly from it. So he either wrote that sentence in Un di velt or he copied it from Un di velt for La Nuit. In any event, he has never rejected that sentence as a mistake, nor was it changed in Marion Wiesel’s 2006 translation … perhaps because it appears in the Yiddish Un di velt.

What is the official narrative and what is its source?

There is no easily determined source for the narrative. It consists of the story that the Germans returned to Birkenau on Jan. 20th to blow up Crematorium II and III in order to destroy the evidence of the “gas chambers.”

According to web-based Holocaust Research Project:

On 20 January 1945 an SS division under SS–Corporal Perschel destroys Crematorium II and III and abandons the camp. On 26 January an SS squad blows up Crematorium V, the last of the crematoriums in Birkenau.

An entire division was required to explode two measly crematorium buildings?! I guess what they’re trying to say is that an SS team returned to Birkenau, after the bulk of the prisoners had been evacuated and before the Russians first arrived, to destroy the “evidence.” In other words, they didn’t plan well enough to do it ahead of time so had to sneak back after they had already abandoned the camp. But wouldn’t the ex-prisoners who remained in the hospital buildings that were very close to Crema II and III have heard and seen the explosions? Yes, of course they would, although we don’t have any statements of hospital patients about a demolition in the camp on January 20th.

On Nizkor we find this timetable (source unknown):

“January 20 [1945] … The SS division under Corporal Perschel blows up the already partly demolished Crematoriums II and III and abandons the camp.”

“January 23 [1945] … An SS division arrives in the prisoner’s infirmary camp in B-IIf in the afternoon…they set 30 storeroom barracks [the “warehouses”-cy] in the personal effects camp on fire…. These barracks burn for several days. After the liberation, 1,185,345 pieces of women’s and men’s outerwear, 43,255 pairs of shoes, 13,694 carpets, and a large number of toothbrushes, shaving brushes, and other items such as protheses, glasses, etc., among other things are found in the six remaining partially burned barracks.” [Note: The warehouse barracks were right behind the hospital barracks, where most of the remaining prisoners were staying.]

“January 26 [1945] … At 1:00 A.M. the SS squad with the task of eliminating the traces of SS crimes blows up Crematorium V, the last of the crematoriums in Birkenau.”

“January 27 [1945] …The first Red Army reconnaissance troops arrive in Birkenau and Auschwitz at around 3:00 P.M. and are joyfully greeted by the liberated prisoners….

[Note: If the clothing warehouses were set on fire on Jan. 23, would they still be burning on Jan. 28, 29, 30… however long it took the Soviet movie makers to get there?-cy]

Above: Underneath the roof of the dynamited Crema II in 2005. Below: Ruins of Crema III taken at the same time (Photos courtesy of Scrapbookpages.com)

Above: Underneath the roof of the dynamited Crema II in 2005. Below: Ruins of Crema III taken at the same time (Photos courtesy of Scrapbookpages.com)

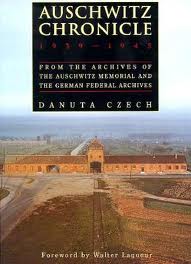

In Danuta Czech’s Calendarium [Auschwitz Chronicle 1939-1945, Henry Holt, 1990, 855 pp], probably the source of the above, Czech has the final destruction of Cremas II and III taking place on January 20, 1945. Her basis for that are two “eyewitnesses”—female prisoners Anna Kowalczyk and Maria Matlak—who had remained behind and who said that they “saw” the SS in the camp on that day, and from them came the name of SS-Unterscharführer Perschel, who had been “capo of the Work Service in the women’s camp”, so they knew him. These two women said that after ordering 200 women outside the camp gates to be shot (!), Perschel selects a group of male prisoners from the infirmary (!) to carry boxes of dynamite to Cremas II and III. This is the entire basis for Czech’s claim that the SS returned on Jan. 20th and blew up the Cremas! This is what the Holocaust Industry passes off as proof.

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum uses Czech’s timeline, but leaves out the Jan. 20-26 demolition dates.

USHMM’s Chronology of the Holocaust

JANUARY 17, 1945

As Soviet troops approached, SS units evacuated prisoners in the Auschwitz camp complex, marching them on foot toward the interior of the German Reich. The forced evacuations came to be called “death marches.”

JANUARY 27, 1945

Soviet troops liberated about 8,000 prisoners left behind at the Auschwitz camp complex.

I did not find anything on the Auschwitz-Birkenau website either. So one thing is clear: these dates about the SS divisions returning to blow up and burn down “evidence” are not sourced in documents. No order has been produced, and there would have to be an order. The SS troops couldn’t just do whatever they decided on their own. The witness statements are of dubious value, to say the least. Thus, there is no reason to believe the “Germans-blew-up-the-Cremas-to-hide-evidence-of-crimes” story, except that it became part of the official narrative that was constructed at Nuremberg. It is held .. it is believed … it is thought … but it is not proved.

What does a January 20th liberation mean?

A January 20th liberation by the Soviets means the Germans could not have returned to blow up the crematorium buildings, nor could they have burned down the clothing warehouses. It means that only the Soviets could have done it—because only the Soviets had the opportunity to do it.

Would they do such a thing if they really held “evidence of German crimes” in their hands … in the form of real gas chambers? Certainly not. It was because there was no evidence of German crimes in those buildings. It was to cover up the lack of German crimes that they would destroy the buildings. They reasoned (in their sly, dishonest minds) that the best course would be to invent German crimes, which they had already been doing since 1941 (and the Polish Resistance had been spreading gassing rumors since 1942), and to simply add the destruction of the buildings by the SS to their list of “German crimes.”

I came across an exchange between two revisionists that took place in 2005. It went like this:

1st revisionist: For me, it seems more plausible that the Soviets (or some other party) destroyed the crematoriums after the war to support their alleged story of genocide. Then they were able to spread this story: “Why would the SS have destroyed the cremas, if not to cover for mass homicide.”

2nd revisionist: I agree with you totally. I also believe the Russians blew them up to destroy the solid evidence that would contradict the lies they were cooking up and about to release on the world.

From the time the Red Army arrived, Soviet Intelligence was in total control. None of the other Allies were allowed to enter this region. In 1947, the Soviets rebuilt the crematorium in Auschwitz I to make it appear that it was used as a gas chamber. Even so, it is not a convincing job. In Birkenau, it was easier to destroy the crematoriums and tamper with them (such as breaking holes into the collapsed roof to match the absurd story of Zyklon B thrown into the chamber through the holes in the roof.) About these chiseled-out holes, court-certified expert engineer Walter Luftl, as quoted by Germar Rudolf in his book Lectures on the Holocaust (Theses and Dissertations Press, 2005), p 246, said:

In the cellars of Crematories II and III, the entire force of explosion was forced upward, causing heavy damage to the roofs. The hole under consideration is characterized by the fact that all the cracks and breaks of the slab are found around it, but do not go through it! According to the rules of construction technology this fact alone proves with scientific certainty that it was made after the roof had been destroyed.

Photo documentation and literature of what the Russians found is scarce.

Why is it that the earliest photo that exists of the destroyed Crema II is this one from February 1945? Why is there no photograph from the time the Russians arrived in January, since such a picture would have much greater propaganda value? To properly document such an important discovery—that the Germans had blown up evidence of crimes as they retreated—many photographs would need to be taken. What happened? Did they run out of film?

Why is it that the earliest photo that exists of the destroyed Crema II is this one from February 1945? Why is there no photograph from the time the Russians arrived in January, since such a picture would have much greater propaganda value? To properly document such an important discovery—that the Germans had blown up evidence of crimes as they retreated—many photographs would need to be taken. What happened? Did they run out of film?

As Tom Moran noted on the Nizkor page linked to above: “It is written the Soviets installed an “Extraordinary Commission” the very day of liberation of the camp and yet no photos are presented on the Holocaust promotional circuit of these buildings, or what was left, lest of course the one and only photograph of Crema II which is nothing more than a collapsed slab of concrete.”

In Photographing the Holocaust: Interpretations of the Evidence (Tauris & Company, London, in association with The European Jewish Publication Society, 2004) on page 143, author Janina Struk writes:

On 28 January, 1945, the day after the camp was liberated by the Red Army, Adolf Forbert was one of the first Polish soldiers to arrive. He described his first impression of Auschwitz as being as “macabre” as Majdanek but on a larger scale.

On 28 January, 1945, the day after the camp was liberated by the Red Army, Adolf Forbert was one of the first Polish soldiers to arrive. He described his first impression of Auschwitz as being as “macabre” as Majdanek but on a larger scale.

Forbert stayed to film everything he could, but with only 300 meters of film, a camera of the Bell and Howell type manufactured by the Russians, and one Leica, the possibilities were limited.

He said there were 500 sick women in the women’s hospital in Birkenau. The fate of Forbert’s film and photographs of Auschwitz is not known.

The film “Chronicles of the Liberation of Auschwitz,” made in 1945, is attributed to four Soviet army filmmakers. The majority of the now well-known stills of the liberation are taken from this film.

Soon after liberation, other photographers began to arrive to take photos for the special investigative commissions established to collect evidence of Nazi crimes.

(Barbie) Zelizer [author of books on the Holocaust and Media -cy] states there was an inconsistency in the way the Soviets reported the liberation of the camps in Eastern Europe generally. Not only did they not publicize the liberation of Auschwitz until after the liberation of the western camps, but they didn’t issue press releases about the extermination camps at Belzec, Sorbibor and Treblinka.

Although their [Red Army] advances through Silesia were reported in detail, there were only two brief mentions about the liberation of the camp. On 29 January in the Guardian, one sentence. On 3 February, the Daily Express had one column on page 4 about the liberation.

In Poland itself, few images were published of the liberation of Majdanek or Auschwitz-Birkenau.

It would be decades before images of Auschwitz would become familiar in the West.

There is almost nothing in Holocaust literature on the arrival of the Soviets to Auschwitz-Birkenau. The only documentation was put together afterward. All the photographs that are exhibited in the various memorial museums (USHMM, Yad Vashem, A-B Memorial & Museum, etc.) and in books, are “stills” from a propaganda film(s) made many weeks or months later … or they are retouched photos, photo-montages and mis-labeled photos that actually show other places and even other national-ethnic groups.

The narrative of a January 27th liberation comes unraveled when scrutinized

Why all the deception? Why all the trickery? The arrival of the Soviets on Jan. 20 instead of Jan. 27 explains it. The person who runs Scrapbookpages Blog and calls himself “furtherglory” once wrote this to a commenter on his blog:

I have read in several books that the Soviets arrived in the area on January 17, 1945 and were in the area for 10 days before they “liberated” the prisoners on January 27, 1945. I have read at least one Holocaust survivor book which said that the warehouses were still there after the Germans left on January 18, 1945. I believe that the Soviets burned down the warehouses. With all the evidence gone, no one could dispute the Soviet testimony at the Nuremberg IMT that 4 million people had been killed at Auschwitz.

The Central Sauna building at Birkenau was kept off limits to tourists for 60 years. Why? The Sauna building was where the clothes were disinfected. Why weren’t tourists allowed to know that the Germans were trying to prevent typhus epidemics?

Also, keep in mind that the last group of Sonderkommandos were marched out of the Birkenau camp and I think a couple of them are still living. Why did the Germans allow these witnesses to live?

Cremas IV and V were also shower houses with hygiene facilities for disinfection. They were close to The Central Sauna and served the same purpose although on a smaller scale. Consider that if the only shower facility in the entire camp was the rather modestly-sized one in The Sauna building, it would not have been at all adequate. But with “Cremas IV and V” also serving that function, they got by. Crema IV was heavily damaged in an uprising on Oct. 7, 1944. Both were ultimately totally destroyed, but the question remains—by whom?

The answer has to be by the Russians themselves. And it is Elie Wiesel who has told us. Just as with his failure to mention “gas chambers” in his book Night, Wiesel falls out of step with the official storyline at times and lets the truth slip out. Was he just saying what most people knew at the time, in spite of what was dreamed up at Nuremberg? I think so. He wrote this in 1954. Not even Elie Wiesel should confuse 9 days with 2 days when it comes to a matter of life or death. Which brings up another question: Is it reasonable that the prisoners left behind in an unguarded facility would just hang around for nine days waiting for the feared “Red Army” to arrive? Would they not take off once they got the chance? Elie says he was one of the hospital patients, his father being allowed to stay with him, yet they both were capable of going on the evacuation march and keeping up with the pace. Thus, many others lying around in the hospital surely could do the same. That is, unless the Soviet representatives surprised them by showing up already on the 20th, before they could prepare themselves to leave.

The story of the Auschwitz liberation is as cloudy as it gets. It has been told in emotion-wrenching photographs that were all staged by Soviet photographers and film makers in the following month of February and even March–every one of them–and by revengeful witnesses who were coached in what to say. As portions of the book by Janina Struk point out, time would pass before a final solution of what happened at Auschwitz could be cobbled together for public consumption by Soviet propagandists.

20 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: Auschwitz Liberation, Crematoriums II and III, Elie Wiesel, Night, Un di velt hot geshvign,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Tuesday, May 8th, 2012

By Carolyn Yeager

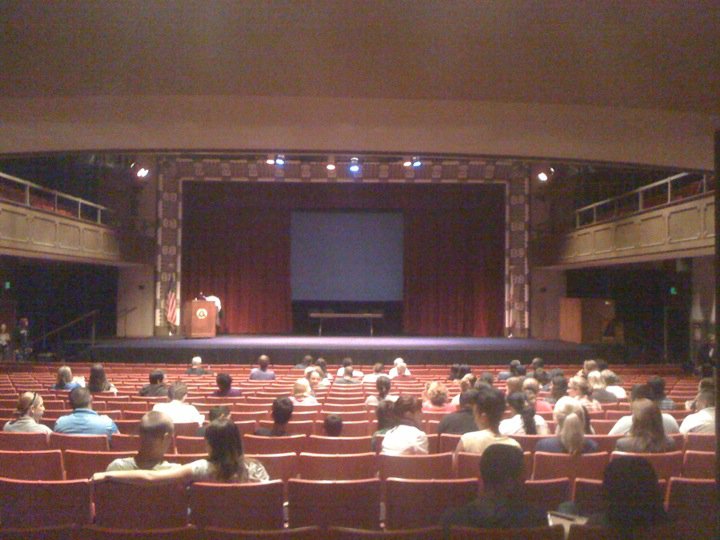

Reportedly “thousands of students” listened to Elie Wiesel on Sunday night, May 6, in the Cintas Center in Cincinnati as he intoned his usual theme: “We haven’t done enough; we still haven’t learned from the Holocaust.” [Right photo shows one section of the Cintas auditorium interior, which is home to the Xavier basketball team.]

Reportedly “thousands of students” listened to Elie Wiesel on Sunday night, May 6, in the Cintas Center in Cincinnati as he intoned his usual theme: “We haven’t done enough; we still haven’t learned from the Holocaust.” [Right photo shows one section of the Cintas auditorium interior, which is home to the Xavier basketball team.]

Who does he mean by “we”? Why, white western (European) man, of course. Not Jews. Nor any other non-whites. They are the ones dying “of famine or of disease or of violence.” As he said, “Every minute today, somewhere in this world a child dies” from one of these three causes, and he asked “How is that possible in a civilized society?”

Civilized? Is the world composed of civilized societies? Most of these deaths of children occur in areas of the world that are not civilized, but Wiesel expects western White societies to be and to feel responsible for what occurs there. This is just one of the dishonest manipulations of thought and speech he exhibits. If you examine his words in any speech you want to name, you discover the irrational element running through it. The guilt-tripping of Europeans. The identification of himself with the innocence of children. He places himself on the child’s side, against what he would call selfish and indifferent White people.

He very quickly brought up Nazi Germany as the perfect example of this, and again his faux incomprehension about “why.” He said of Nazi Germany, “To this day, I don’t understand it. Why the children?” He is lying about the children because certainly the National Socialist regime did NOT go after children. Thousands of children were liberated from the camps, including himself (according to his story) and they were in good health. Pictures of the “boys of Buchenwald” shortly after “liberation,” for example, show sturdy, normal-looking boys. The internment policy did include whole families by necessity; sometimes they could remain together in family camps and sometimes they were separated by sex into sections for men and women.

Wiesel’s general pattern is to lament the state of the world, followed by “Will the world every learn?” or “The world hasn’t yet learned the lesson of The Holocaust.” This makes the Jews the teachers and the overwhelming majority of us who are not Jews the poor students who won’t learn. Wiesel always presents us with the entire world’s ills and expects a solution for the entire world … something that is not a possibility in any event. In this, he reveals his utter lack of intellectual integrity, common-sense reasoning, and good faith.

Wiesel extracts sympathy for himself; talks about crying

After describing his family victimology for the umpteenth time, he did say one thing new! In recounting his rescue from the concentration camp by the US Army, he recalled that “We cried. We discovered for the first time that we could cry.”

Again, who is “we”? Wiesel always said that he felt nothing after his father died; that he shed no tears at the liberation either. “Our first act as free men was to throw ourselves onto the provisions.” (Night, p115) It was later, at the orphanage in France, that he began to feel again, he said in his memoir. But now he’s added a new twist — he cries at liberation. Wiesel goes directly from these touching sentiments to denouncing those who deny the “existence of the Holocaust,” which is more of his dishonest manipulation of speech. Those he calls “deniers” only deny the official narrative of the Holocaust as the Jews insist on it; they do not deny “the existence” of what actually happened to Jews under National Socialism. Big difference, but this difference is denied by the holy holocausters and Wiesel followers. Only their version is acceptable and all must follow it or be called deniers.

Holocaust Denial should be a crime!

Wiesel again calls for the criminalization of “holocaust denial” in the United States. He thinks because this narrative has become sacred to Jews, it should be an exception to the guarantee of freedom of speech that Americans enjoy, and have enjoyed from America’s founding. Think about this. Think about this! This kind of “we come first” attitude is why National Socialist Germany wanted to remove their Jews from the country.

Elie Wiesel is very bold. We must be bold in return. He may feel that at his advanced age he should put it all out there, and, with his untouchable reputation and the protection of the mass media, go for broke. He defended Israel too, as he always does, especially in its formation (in which he played a part), and said he “hopes” for peace—easy to say. Wiesel poses himself as a defender of children, even while Israeli policies kill Palestinian children without a care. Everyone knows this, but at this large gathering, with most students sitting in the cheap seats in the upper balconies, there is no way to shout a question at him.

Robert Ransdell considers his action a success

Ransdell has informed Elie Wiesel Cons The World that he is writing up his May 6 experience to post on the internet under his name, but he sent a long email describing what took place. Unfortunately, he was alone and there was no one to take photographs of him.

Cintas Center showing parking lot

Cintas Center showing parking lot

Upon arriving at the Cintas Center, he says he was already tailed by a motorcycle cop, who, however, did not accost him. After parking his car in the lot and walking a short distance toward the entrance, he was approached by two men in suits who identified themselves as campus police and told him he would not be admitted into the building. Hillel had done it’s job. They took his ticket and gave him a $20 bill to compensate for the cost. Ransdell was dressed in his custom t-shirt and hat which asked the question of Wiesel’s tattoo and stated the $1000 challenge.

Ransdell says he was prepared for this eventuality, so he left and parked across the street. He then stood on a street corner right in front of the main entrance to the Xavier campus where most of the people coming to the event would enter. It was still 45 minutes before 7 pm. He had brought with him a sign which was easily visible, and so he stood there with his sign, wearing his custom t-shirt and hat while the traffic flow built up until it was badly stalled first on one side and then the other, as each lane had to wait to turn into the entrance.

He says he was easily seen by the occupants in the cars since he received stares, visible gasps, sneers and middle fingers from them, while he smiled and waved. Some yelled words such as “bigot”at him, which is clearly the wrong word as he was asking to see a tattoo which Elie Wiesel has always said he has but which he has never shown. (Not to mention that photographs show it isn’t there.) Ransdell said some police were stationed across the street from him, which made him feel safer from the likelihood of someone getting out of a car and coming after him. So, all in all, Robert was a happy camper.

Critics and news blackout

He says he stayed until about 7:15 when traffic became completely normal again. Further details will be in Ransdell’s own written account. But I call him a courageous man for standing up to the power of the Jews in his own town as a known entity. He is a good-looking, well-spoken young man and while I would not have written the flyer exactly as he did, or put on the sign exactly what he did, I only find fault with those “couch quarterbacks” on CODOH Forum who criticize his actions from behind their pseudonyms. (Not all are critical.) If we had just a hundred Robert Ransdells, what an impact we could make. Why don’t we? Ransdell has allies but they are afraid to go to a public function with him! Another one who went out alone to a college campus with flyers about Elie Wiesel’s tattoo was Steve Bock, but these two live almost the entire width of the United States apart from each other.

The Channel 9 news truck was in the area, but made a point to ignore him — another example of the news black-out on any activity that is not good for Jews. They like controlled acts of “antisemitism” to feed their narrative, but do not like to have Elie Wiesel’s self-proclaimed tattoo brought into the limelight. That’s why we use it. It’s the most visible and effective counter to his story of himself as a holocaust survivor. Elie, please show us the tattoo!

10 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: Elie Wiesel, protest actions, Robert Ransdell, Where's the Tattoo?,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Tuesday, May 1st, 2012

By Carolyn Yeager

Updated on May 2, 6:30 p.m. (see below)

Robert Ransdell is a man after our own heart. He’s putting up money to publicize the fact that Elie Wiesel doesn’t have the Auschwitz tattoo he claims to have.

“An Evening with Elie Wiesel” is coming to Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio, Sunday, May 6th. The entertainment/education event is being marketed by CHHE, which stands for Center for Holocaust and Humanity Education. We just finished with Holocaust Remembrance Week in the United States, and now the entire month of May is Jewish American Heritage Month! So people like Elie Wiesel are on the circuit.

Picture at right is used on promotional materials for the “Evening with Elie Wiesel.”

CHHE is worth studying in itself. It shouldn’t pass your notice that “Holocaust” is combined with “Humanity,” cleverly making a connection between the two. Headquartered in Cincinnati at the campus of Rockwern Academy (formerly Yavneh Day School) at 8401 Montgomery Road, Cincinnati, OH 45236, it displays a permanent exhibit named Mapping Our Tears which showcases “a multimedia theater set in a 1930’s European attic that takes visitors back in time.” A portable exhibit of “Out of the Attic” can be taken to schools and other locations (with trained “educators,” of course) for a fee of $350.00 a half-day and $500.00 for a full day. But Mapping Our Tears is also supported by generous benefactors, such as United Way, U S Bank, Time-Warner Cable, Kroger, Proctor & Gamble, Cinergy, Federated Dept. Stores and Frisch’s Big Boy … and one whose logo I can’t recognize. (Anyone in the mood to boycott?) To see the permanent exhibit, it is suggested you give a “donation” of $5 per person. CHHE is a non-tax-paying, non-profit organization … such a laugh.

Left: Henry Fenichel, top speaker, wears a yellow Star of David while conducting a presentation to students.

Left: Henry Fenichel, top speaker, wears a yellow Star of David while conducting a presentation to students.

CHHE has a Speakers Bureau, naturally, featuring “Holocaust survivors, Holocaust refugees, World War II veterans and concentration camp liberators, and other eyewitnesses. Additionally, children and grandchildren of survivors, and trained experts and educators are available to speak to your group.” Also, “A donation to the Center of $100 is suggested to cover the costs incurred by this program.” I imagine one would be made to feel downright cheap if an even more generous “expression of appreciation” were not given directly to the speaker also. Elie Wiesel is too exalted to be just another available speaker on their list, and absolutely costs more than $100 (LOL) but he is still handled by the Speakers Bureau.

The Center likes to hold major events at nearby Cintas Center of Catholic Xavier University. In the new spirit of Catholic-Jewish reconciliation, the Jesuit university is more than willing to help promote holocaust education. But does the Jewish school or the Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion in Cincinnati (which used to house the CHHE) promote Catholic-Christian history in a way that the Catholics would like? Very doubtful. With Jews, you don’t get an equal exchange.

The poster that advertises the event says “Professor Wiesel’s visit is made possible by The Jewish Foundation of Cincinnati … with their partners The American Jewish Committee, Cedar Village, Jewish Community Relations Council, The Jewish Federation of Cincinnati, Jewish Vocational Service and the Issac M. Wise Temple. In other words, it’s an all-Jewish production. It is Jews, and Jews alone, who present endless programs on the Holocaust to the long-suffering Christians, although the audience will probably be majority Jewish. They make sure to support their own.

Note that there is both a Jewish Foundation of Cincinnati and a Jewish Federation of Cincinnati. The CHHE reminds me of the British HET (Holocaust Education Trust). I feel sure it is patterned after that older, very successful organization.

The man who is sponsoring a $1000.00 Challenge to bring the ‘Wiesel—No Tattoo’ issue to the Xavier campus

Robert Ransdell, who lives in the Kentucky/Ohio area, has been flyering both the University of Cincinnati and Xavier University for the past month — since he found out Wiesel would be making the speech there. He has come up with “The $1000 Challenge”—the money promised to the first person to get Elie Wiesel to show his left forearm and reveal his A-7713 tattoo number … or lack of it. If there is no tattoo visible, no reward will be given. The winner must show proof that Elie Wiesel does have a tattoo—which would require Wiesel’s cooperation.

Ransdell realizes that few, if any, would even be able to get close enough to Wiesel to ask him, but he is trying to make a point with his Challenge. He also tried to place an ad in the Xavier campus newspaper, but it was eventually turned down. Ransdell thinks it’s because his flyering made them aware of his intentions—the ad simply said “Elie Show the Tattoo,” with “Elie” being the name of a band coming out with a new album titled “Tattoo.” Ransdell also posted some of his flyers at Hillel, the “largest Jewish campus organization in the world,” which was probably a mistake since they would then be on the lookout for him.

Ransdell, however, is no novice to this kind of activity. He told me that he has crashed holocaust speaking engagements in the past, including Deborah Lipstadt at Xavier in March 2007, and has had some success for his efforts. Because it was a smaller audience than Wiesel’s will be, Ransdell was able to interrupt Lipstadt’s speech when she started talking about the Holocaust. He asked, “Now which Holocaust are we talking about here, the first or the second?” As the room fell silent, he continued, “are we talking about the one in 1919, when Ilya Ehrenburg claimed that 6 million Jews were being killed in a Holocaust … or the second one?” Lipstadt fumbled for a second and Ransdell rose and said even more before he was ordered to leave. But he continued talking on the way out, and Lipstadt had no answer.

He is not planning to attend the “Evening with Elie Wiesel” himself, but hopes to inspire some action by others with the promise of the $1000 reward. We will report on further developments next week. You can contact Robert Ransdell at [email protected]. He could probably use some financial contributions to help cover his costs, if you feel inclined.

* * *

UPDATE: May 2, 6:15 p.m.

From the Cleveland Jewish News: For the ADL, this is another sign of rising antisemitism.

Hate Fliers target Wiesel’s May speech in Cincinnati

MARILYN H. KARFELD

Senior Staff Reporter |

Anti-Semitic fliers have been posted at the University of Cincinnati and nearby Xavier University, targeting Elie Wiesel, a Nobel Peace Prize laureate and Holocaust survivor, who is speaking at Xavier on Sunday, May 6.

On April 4, about 30 fliers were posted at the University of Cincinnati on and around the Hillel Jewish Student Center, and a couple were found by the student union, said Judith Wertheim, 20, a resident of University Heights and a junior at the university. The fliers were posted a day after Hillel began advertising Wiesel’s speech, which is being presented by The Center for Holocaust and Humanity Education, an independent nonprofit in Cincinnati.

The fliers, which call Wiesel a liar and a fraud, among other scurrilous charges, [No mention of the legitimate question of Where Is Elie’s Tattoo? That is not hate, and it is very dishonest of them to not state the actual contents of the flyer. They are AFRAID of the tattoo question. -cy] were also spotted on the campus at Xavier University, a Jesuit institution that is co-sponsoring his appearance.

In response, the University of Cincinnati’s Undergraduate Student Senate passed a resolution supporting a letter drafted by Rabbi Elana Dellal, executive director of its Hillel, and submitted to the senate by Stephen Lamb, a student intern at Hillel. The letter criticized the fliers’ message, said Wertheim, a senator from the College of Allied Health Sciences.

“We, the student body of the University of Cincinnati, will not stand by as intolerance occurs on our campus,” Dellal wrote in the letter titled “We Will Not Be Silent.”

“We, students and supporters of the University of Cincinnati, understand that denying that the Holocaust happened is anti-Semitic,” the letter continued. [Did the flyer deny the holocaust happened? -cy] “There is no place on our campus for intolerance of any kind, be it religion, race, gender, sexual orientation or ethnicity.”

Jewish students active at Hillel, who plan to attend Wiesel’s speech, also decided that doing more than writing the letter and alerting the student government to the fliers was “giving too much power to this person posting them,” said Wertheim. “This wasn’t a threat of violence. But we don’t condone hate speech [only their own -cy], which is why we brought it to the student government to get more backing.”

When informed of the fliers, university officials said they would “keep an eye out,” said Wertheim. “It was very clear the university is very supportive of Hillel.”

The Center for Holocaust and Humanity Education is presenting Wiesel, a Romanian-born Holocaust survivor and author, with financial support from the Jewish Foundation of Cincinnati. Wiesel’s first book “Night,” the 1956 memoir of his experiences in Nazi concentration camps including Auschwitz, has sold millions of copies. [Why does the author of a 10- million-plus-selling-book need financial support? And 1956 is not the publication date for Night, but for the Yiddish book Un di velt hot geshvign … the one Elie never talked about until Nikolaus Grüner brought it to public attention after the 1986 Nobel Prize awards. -cy]

The author of the flier identifies himself as Robert Ransdell, coordinator of Cincinnati’s unit of the National Alliance, a white supremacist group that has dwindled in support in recent years and only has about a dozen active participants, said David Schneider, an Anti-Defamation League investigative researcher based in Chicago.

“Elie Wiesel, because of his prominence and his status, attracts the attention of Holocaust deniers and white supremacists,” said Schneider.

Wiesel has not spoken in Cincinnati in a decade, said Sarah Weiss, executive director of The Center for Holocaust and Humanity Education. Many schools in the area include “Night” in their reading lists, and there are already 4,000 reservations for the event, including 2,000 students, she said.

“While it is unfortunate that individuals who hate and want to deny history are present and visible and active, it’s a small minority of people,” said Weiss. “We should use this to energize and galvanize efforts around Holocaust education. Maybe, in a small way, it’s an opportunity for us.”

Publicizing hate-mongering activities requires walking a fine line, said Nina Sundell, area director of the Anti-Defamation League, whose region covers Ohio, Kentucky, West Virginia and western Pennsylvania.

“The purpose of distributing the fliers is to bring more attention to a hateful activity,” she said. “There’s a downside to publicizing that as more people hear their message. However, one of the best ways to fight hateful rhetoric and speech is through other speech, the reverse type. It’s always a judgment call” whether or not to make these activities public.

Sundell has not decided if she should become involved in the Cincinnati incident. “Would it assist them in putting forth a positive message or spread the hateful message further?” she asked. “We feel it is the ADL’s role to bring these issues to light, but we need to examine this situation further to decide if we take any action.”

[email protected]

The lesson here, dear readers, is that even the smallest of actions against St. Elie of Wiesel will bring down a torrent of abusive reaction from the guardians of the most powerful narrative in the Jewish arsenal.

8 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: $1000 Elie Wiesel Tattoo Challenge, Center for Holocause and Humanity, Elie Wiesel, Holocaust fraud, Robert Ransdell, Xavier University,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Wednesday, April 25th, 2012

By Carolyn Yeager

Do we have a stupid President, or what?

Do we have a stupid President, or what?

On Monday, April 23, U.S. President Barack Obama toured the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum with Elie Wiesel as his guide. Following the tour, both Wiesel and Obama gave boring, highly hypocritical speeches to the assembled diplomats, Jews, Shoah survivors, supporters and workers. Both speeches together lasted about 35 minutes. (Pictured right, Wiesel and Obama hug between speeches)

During Obama’s talk, he recalled a previous time that Elie had guided him through one of the Shoah’s sacred shrines–Buchenwald, in June 2009. At the 11:10 mark of this video, Obama remembers:

We stopped at an old photo, men and women lying in their bunks, barely more than skeletons, and if you look closely you can see a sixteen year old boy, looking right at the camera, right into your eyes … you can see Elie.

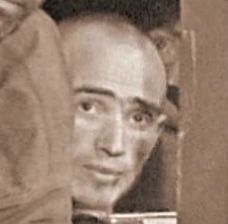

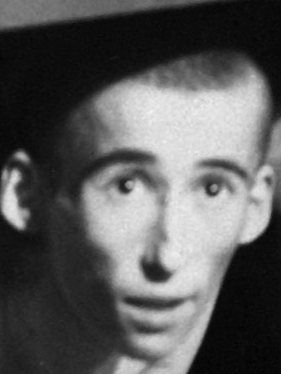

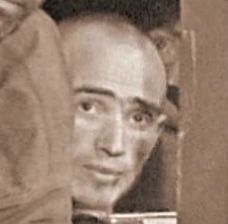

President Obama was talking about this old photo, which is a cropped version of the original.

This photograph was taken on April 16, 1945 when Elie Wiesel could not have been in it because he was in the hospital at Buchenwald deathly ill from food poisoning, according to both Night and his memoir All Rivers Run to the Sea.

This photograph was taken on April 16, 1945 when Elie Wiesel could not have been in it because he was in the hospital at Buchenwald deathly ill from food poisoning, according to both Night and his memoir All Rivers Run to the Sea.

Obama made a big boo-boo in saying “men and women” were in the photo, lying in bunks together. But we already questioned his intelligence, so we’ll pass that by. The bigger mistake he made was identifying the face in the far upper right as Elie Wiesel. His presidential aides should familiarize themselves with this blog before their boss’ next meeting with the Holo idol. This site has proven that it is not Elie Wiesel in that picture, especially here and here.

Judge for yourself from this cleaned up, unretouched enlargement of the round-headed man (right), found to be in his 30’s by a computer program designed by Apple. Or check out Computer program judges “Elie Wiesel in Buchenwald” to be 30-36 years of age once again.

Judge for yourself from this cleaned up, unretouched enlargement of the round-headed man (right), found to be in his 30’s by a computer program designed by Apple. Or check out Computer program judges “Elie Wiesel in Buchenwald” to be 30-36 years of age once again.

Compare this face to a real 16 year-old—Nikolaus Grüner in the far lower left of the picture above.

This tells us that President Obama doesn’t think for himself, but accepts whatever he is told by members of the Jewish race, like Elie Wiesel. But we already knew that. Elie says, “That’s me,” and Barack says, “My, so it is.”

Obama continues recalling the Buchenwald meeting:

And at the end of our visit that day, Elie spoke of his father. “I thought one day I would come back and speak to him,” he said “of times of which memory has become a sacred duty of all people of good will. ” Elie, you’ve devoted your life to upholding that sacred duty. You’ve challenged us all as individuals and as nations to do the same with the power of your example, the eloquence of your words … as you did again just now … and so to you and Marion we are extraordinarily grateful.

First, who is we? The entire U.S. citizenry? I’m sure there are many who, like me, opt out of that sentiment and are not grateful to Elie Wiesel. Think how Wiesel uses the word “memory” here. “Memory should become a “sacred duty of all people,” is what he is saying. How can “memory” alone be a sacred duty? But he is meaning a specific memory of the Jewish Holocaust, nothing else. He doesn’t want to say that out loud for all us non-Jews to hear, but we’re supposed to pick it up anyway. We know he means only the memory of the Jewish “holocaust” because he supports the Holocaust Lobby’s condemnation of the Germans’ right to their memories, doesn’t he? If any nation’s memories conflict with the sacred Shoah narrative, they should be suppressed, even criminalized. Wiesel said as much in his speech. In the case of Germany, their non-shoah-approved memories are criminalized (see here). It is the same in Austria and to a lesser degree in many European countries, and Wiesel is on record for favoring criminalization in the United States! Barack Obama is promising that “as a nation” we will follow Elie Wiesel’s example.

You should also be aware that the Shoah narrative is still in flux, still changing, so we don’t even know what we’re in for.

Barack Obama, representing the American people, is committing a great injustice to most of us in order to beg for the Jewish vote. How far will we allow the Jewish takeover of America to go?

UPDATE: April 26, 8 p.m.

A perfect example of the hypocrisy of Wiesel’s “sacred duty of memory” was offered today in a news story from Europe. The U.S. State Department’s “special envoy to fight global antisemitism” Hanna Rosenthal was touring Latvia after meeting earlier with the mayor of Malmo, Sweden. In Latvia, she pressed the Latvian leadership on their country’s continued commemorations of Latvian participation in the Waffen SS, the military wing of the National Socialist party, which included volunteer divisions from all over Europe. Many Latvians consider the volunteers who fought against the Soviets to be heroes of the nation. To Rosenthal’s objections that this amounted to condoning the killing of Jews, they said their history is “complicated” and they don’t see it in simple right/wrong terms. But Rosenthal insisted, with the weight and power of the United States government behind her, that such a commemoration was “offensive to Jews.” Because it is offensive to Jews, the Latvians’ sacred duty to their memory of resisting the takeover by the Soviet Union cannot be allowed.

What could show more clearly that it is indeed only the memories sacred to the Jews that all the world is expected to honor. Our own sacred memories, whatever they may be, must come second to theirs. Who in their right mind accepts such rules?

8 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: Barack Obama, Buchenwald, Elie Wiesel, USHMM,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Friday, April 20th, 2012

By Carolyn Yeager

From the website of Chapman University:

Elie Wiesel will return to Chapman University on April 15-22. His annual one-week visit marks the second year of his five-year appointment as a Distinguished Presidential Fellow at the university. While on campus, Wiesel will meet with [selected] students and faculty and be a guest speaker in various classes.

This year, Wiesel plans to present four “Conversations” during his visit. The moderated discussions (which will be open only to the university community, not to the general public) will focus on themes central to his work and to the university community. Scheduled topics include:

- “Why Study?” (moderated by Daniele Struppa, Ph.D., Chapman University chancellor)

- “Why Write?” (moderated by English professor Patrick Fuery, Ph.D.)

- “Why Be Just?” (moderated by Tom Campbell, dean of Chapman University School of Law)

- “Why Believe?” (moderated by Gail Stearns, Ph.D., dean of the Chapman University chapel)

Chapman University President James L. Doti, Ph.D., sees this as another exceptional learning experience for the Chapman community. “Elie Wiesel challenges us to ask ourselves the big questions,” Dr. Doti said. “He believes that as human beings, we are defined more by the questions we ask than by the answers we give.* I am especially excited that our students will be able to join with Professor Wiesel in a week of questions and conversations. I know this week will have an impact on their years here at Chapman and on the way they look at the world.”

Elie Wiesel first visited Chapman University in April 2005, when he took part in dedication ceremonies for the university’s Sala and Aron Samueli Holocaust Memorial Library. His second visit came in April 2010, when he spoke to the university community and was guest of honor at a gala marking the 10th anniversary of the Rodgers Center for Holocaust Education and the Stern Chair in Holocaust Education. That same year, he accepted a five-year appointment as a Distinguished Presidential Fellow at Chapman University. In that role, Wiesel is invited to visit Chapman annually to meet with students and offer his perspective on subjects ranging from Holocaust history to religion, languages, literature, law and music.

* Here at Elie Wiesel Cons The World, we have defined ourselves by asking the same question “Where’s the Tattoo?” for two years, but have received no answer from the professor. If you pay attention, you will see that Wiesel’s whole ploy is to ask questions, while always saying, “I have no answers.” Only on the witness stand in a court of law does he have to answer.

That’s it, folks. No follow-up stories, no photos, no comments from students; it’s all being kept totally private this year.

Do you think it’s because of our coverage last year? Absolutely, yes! The Wiesel forces, while totally ignoring us outwardly, have changed their tactics and the visibility of “the man” because of our lampooning of his speeches and our use of the school’s photos, and comments from faculty and students. Elie Wiesel Cons The World is the only media that has done this. Thus … no more fun for us.

Even the Panther student newspaper received it’s instructions — it had only one announcement article, basically the same as the University website write-up. The Orange County Register had no coverage as it did last year.

Above: Spacious interior of auditorium in Memorial Hall. Right: Exterior.

Above: Spacious interior of auditorium in Memorial Hall. Right: Exterior.

What I can tell you is that the Chapman students are also being deprived. Five out of the nine comments to the announcement on the school website (as of this writing) were from confused students wanting to know if they could attend Wiesel’s Thursday night speech at Memorial Hall. This was the answer they got:

The 7 p.m. Evening of Remembrance at Memorial Hall is open to the public, but advance registration was required and due to the popularity of this event, all seats are reserved at this time. But there is a chance that some stand-by seating may be available just prior to the start time. Likewise, stand-by seating may be available at Friday’s “Conversation with Elie Wiesel” at 11 a.m. in the Fish Interfaith Center.

I’m sure the majority of students at Chapman don’t get even a glimpse of Wiesel during his week-long stay, let alone have the privilege of suffering through one of his “conversations.”

Today being Friday, it is all over now. Even though Wiesel’s contract runs through Sunday, he’s probably completed all he has to do to earn his … what? $25,000.00? Or more? Maybe 5 times $25,000. Is that possible? Sure it is … with all those rich, uh, Californians.

Tuesday, April 17th, 2012

A Swedish reader has informed this website of a new computer program that gives the approximate age of a person by scanning their photograph. Scroll down the linked page to see six examples. [Unfortunately, as of 12-5-15 this page is no longer online, at least not at the address it was. But I found two write-ups about it here and here. It does exist.]

Our reader took advantage of the website’s free demonstration offer and tested two faces from the famous Buchenwald liberation photo taken on April 16, 1945. Nikolaus Grüner is in the lower left of the FBLPhoto, and in the background is the round-headed man who is claimed to be Elie Wiesel. These are the results the computer program gave him.

Above: Estimated age 16 years (exactly the age Grüner was at the time)

Above: Estimated age between 30 and 36 years (Elie Wiesel was only 16 at the time)

This does not surprise us. It fits what we can see with our natural eyes and brain — and what other evidence has told us. But it’s nice to know that a program designed by the bright folks at Apple has confirmed it.

6 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: Elie Wiesel, famous Buchenwald photo, Nikolaus Grüner,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Saturday, April 14th, 2012

By Carolyn Yeager

Wiesel rushes to the defense of Israel once again, proving he is always a political person ahead of being an artistic person.

Zionism has always come first for Elie Wiesel. You might even say all his writing has been in the service of Zionism, one way or another. Now a poem made public by one of Germany’s most famous novelists is causing an uproar in the Jewish/Israeli world, of which Wiesel is an integral part. The poet is Günter Grass; the poem’s title is “What Must Be Said.” It is a criticism of Israel’s nuclear capability and it’s willingness to use it against Iran.

Zionism has always come first for Elie Wiesel. You might even say all his writing has been in the service of Zionism, one way or another. Now a poem made public by one of Germany’s most famous novelists is causing an uproar in the Jewish/Israeli world, of which Wiesel is an integral part. The poet is Günter Grass; the poem’s title is “What Must Be Said.” It is a criticism of Israel’s nuclear capability and it’s willingness to use it against Iran.

In an article in the New York Daily News, Wiesel for the second time in the past month, speaks out on a controversy affecting Jews and Israel. While Wiesel is often portrayed as a kind of suffering saint who stays above the fray in his capacity as “teacher” and one who represents “victims of the Jewish holocaust” for the sake of greater humanity, this has never been the case in reality. He is a scrapper and a partisan in every circumstance involving Israel. Everything he does is done to advance the interests of World Jewry. This latest article makes it clear enough.

It is titled “Guenter Grass’ buried hatred comes to light.” The subtitle brings out that “He once served in the Nazi Waffen SS; today, he is attacking Israel.”

It is titled “Guenter Grass’ buried hatred comes to light.” The subtitle brings out that “He once served in the Nazi Waffen SS; today, he is attacking Israel.”

Well, that pretty much covers the Jew’s reasons why we should hate Grass. He was a Nazi! He’s been a secret Nazi, therefore a Jew-hater, all along! He is not an honest man. Therefore, ignore what he has to say … a version of “attack the messenger,” a tried and true tactic which Wiesel is not above using.

This particular spat can be seen as another chapter in the historic German-Jewish conflict between two nations that are at eternal odds with each other. The idea that these two “races” will ever overcome their inherent “unlikeness” and be able to live together is a pipe-dream. It never will be, as they are opposites. The problem with Grass’ reasoning is that he believes a reconciliation is possible, and has even been made. As long as he holds this belief he will never get it right.

* * *

The following are some highlights from what Wiesel wrote, with commentary by me. You can read the entire article by following the link above.

Wiesel: […] the German Nobel Prize-winning novelist Guenter Grass has obviously chosen to set himself up as judge over the state and people of Israel.

As we know, Elie Wiesel has since even before 1945 set himself up as judge over the nation and people of Germany. But, of course, in Wiesel’s very biased mind he has every right, while Grass has not. Grass, in the eyes of the Jews. is a German perpetrator without any rights at all.

Wiesel: [Grass’ poem] makes the argument that Iran is not, in fact, pursuing nuclear weapons — and that Israel is bent on killing Iranians by the millions. […] How dare he? What does he know about the nuclear sciences? What moral credentials could he claim to possess in order to act as accuser of the democratic Jewish state?

Is Iran pursuing nuclear weapons? There is no evidence that it is. Further, Iran has been a peaceful nation for hundreds of years. If it did make a decision, several years down the road, to produce a nuclear weapon as a defensive measure, it has every right. Iran is a legitimate nation with an immensely long history, that joins with and follows the rules of international legal organizations, while Israel is a rogue state that ignores and disobeys every international law.

So Wiesel’s “how dare he?” is a totally arrogant outburst of someone who’s had way too much privilege in his life … someone who has gotten away with too much. How dare Wiesel question Grass’ moral credentials. In my opinion, they are about on the same level of morality—they are both comfortable with lying—although Grass has bought into the guilt-trip leveled at Germans, while Wiesel rides the high-horse of Jewish-invented victimhood at German hands. Therefore, Grass has no permission to criticize anything Jewish and needs to be put back in his place.

Wiesel: Clearly, had the Swedish Academy known of his secret [Waffen SS membership], it would have had some difficulty awarding him the Nobel Prize.

Ha! Similarly, if the Nobel Peace Prize committee had known that Wiesel lied about being in the famous Buchenwald liberation photo (not to mention all the lies in his book Night) they would certainly have had difficulty awarding him that prize! Wiesel is skating on thin ice here, but then that is typical of him and his ingrained chutzpah.

Wiesel: [Grass’] hatred of Israel, a land founded as the homeland of the Jewish people, is in his poem. In fact, it is the poem.

The whole world is coming more and more to hate Israel. In fact, it is impossible for decent people not to hate Israel. If Israel represents what the Jewish people are, what does that tell us? Wiesel should really wake up and stop beating a dead horse.

Wiesel: Well, he isn’t the first to claim that the Jewish people’s aim is planetary destruction. Adolf Hitler and Joseph Goebbels preceded him in that kind of propaganda.

Bring up the Hitler card, why not? It’s another tried and true tactic. But what is the Jewish people’s aim if not to own the whole world? Their rationale is sometimes given as ” to prevent their own persecution at the hands of the rest of the world.” But it is not a justification, though they think it is. Hitler and Goebbels had more justification for wanting the majority of Jews out of their country in the 1930’s, as do many Americans today, as do the Palestinians. How many nations today would just like the Jews to go away?

Wiesel: Sadly, these despicable accusations come from someone who ranked among the great intellectual minds of postwar Europe.

Grass was never a great intellectual mind. He is not a successor to Goethe and Schiller, who loved Germany and would have stood up and told the truth about her rectitude. The Jewish-controlled media portrayed Grass as great because he acted the role of the perfectly contrite post-war German. For that, he was celebrated and given every accolade. He sold out to the devil, just like Faust.

Wiesel: Iran’s ruler Mahmoud Ahmadinejad is the world’s foremost Holocaust denier. Everyone who reads knows that. But not Grass.

Perhaps Grass is tired of being a holocaust believer. Maybe that will come next? But I wouldn’t count on it because he is a leftist and their power is based on the holocaust.

Wiesel: [Grass] accuses the Israeli leader (Netanyahu), and consequently his nation, of planning mass murder against Iran—and furthermore, warns German Chancellor Angela Merkel of becoming an accomplice to this crime if she helps Israel.

This is so interesting! Wiesel has repeatedly accused (and still does) Adolf Hitler and “his nation” of planning mass murder against European Jews. The difference in his biased mind between his accusations and those of Grass is that Germany was guilty but Israel is not. Yet there is more evidence by far of Israel’s guilt (and from 1945 onward) in wanting to murder the Germans, plus the British and the Palestinians, than of any plan by Germans to murder Jews. You don’t believe that? If so, it’s because you haven’t looked into it for yourself, but have believed Jewish-controlled media all this time.

The Israelis and Wiesel greatly fear losing German support. It is the United States that keeps German leaders like Angela Merkel in line.

Wiesel: There were times when I even felt close to [Grass]. Now I see in his hatred an abyss I shall not cross. He has gone too far.

It’s only normal practice that Wiesel “felt close” to the German writer as long as he spouted praise for Zionism and Israel, and emphasized German Guilt—characterizing it as never-ending. Then, he was a great German! Now the slightest divergence from that stance … the smallest challenge to Israel to stop its war-mongering and bullying … is enough to create an uncrossable “abyss” between them. Günter Grass will never be forgiven. Let’s hope he will forego asking for it, or seeking it in any way, because it will never be granted him. He has “gone too far.”

UPDATE April 15, 1 pm: I’m sure Elie Wiesel now repeats Yemach shemo (meaning “May his name be erased”) every time his says the name of Günter Grass. Orthodox Jews add this Hebrew phrase whenever they mention the name of a great enemy of the Jewish nation past or present. Also here the best answer at this site informs us that the phrase when applied to Jesus’ name means to exterminate the spirit of the Christ (the Logos) and to liquidate his followers like the Jewish “Bolsheviks” did to 66 million Orthodox Christian Russians. “

This recalls to my mind the insistence of the Holocaust-believing Jews to interpret the German word ausrotten which means “to get rid of” or “to root out” or “to eradicate” as “to exterminate“, giving it the sole meaning of “to murder.” Do Wiesel and other Orthodox Jews take the Hebrew word Yemach shemo as literally as they do German words? Something to think about.

15 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: Elie Wiesel, Germany, Günter Grass, Israel,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Saturday, March 24th, 2012

By Carolyn Yeager

In an article titled “The Tragedy in Toulouse,” dated March 21, Elie Wiesel reveals once again his belief that Jewish pain is the only pain that matters. He also suggests that this idea has been held firmly in the Jewish mind for 5000 years–if you believe they’ve actually been around that long.

The background for Wiesel’s essay is the death of seven persons (four of them Jewish) by a gunman on a motorcycle, identified as Mohammed Merah, a 23-year old French National of Algerian origin.

* * * *

To provide my own background to this article, I am reproducing a picture and some text from The Guardian in January 2009.

At least 14 more Palestinian children were killed in the Gaza Strip yesterday as the misery and terror of civilians trapped by the Israeli bombardment intensified.

With Israel defying mounting international demands for a ceasefire, aid workers warned of a humanitarian crisis facing terrified families trapped in their homes with little power, food, fuel and medicine.

The death toll passed 535 as planes, helicopters, artillery and tanks pounded the Palestinian territory for a tenth day.

At right are 3 innocent murdered children whose deaths were not mourned by Elie Wiesel or most Jews in the world, even though their deaths were caused by Jews. Where is the anguish expressed by politicians and presidents for these three children?

* * * *

Merah, now dead himself, killed three French paratroopers of North African origin in drive-by type shootings on a motorcycle. In the aftermath of these three murders, we heard only cries that the perpetrators must have been right-wing, neo-nazi fanatics. A few days later, four Jews (including three children) were killed in the same fashion. Now the cries of anguish reached much higher levels and the media and left-wing politicians went into a frenzy, demanding that the “neo-nazi, far-right extremists” who must be responsible for such a crime be driven from French society and political intercourse.

When it was determined the shooter was an Islamic extremist, not white, the print and internet pundits became focused almost solely on the three Jewish children, and the theme became antisemitism. The French paratroopers of Algerian descent were all but forgotten. In addition, France felt the need to launch it’s biggest manhunt in living memory—anti-terrorist police were sent from Paris, and thousands of policemen were put on the case (according to the Economist).

Into this volatile situation comes Elie Wiesel with a short essay that, in his trademark way, says nothing of substance but accuses millions of “not caring enough” about the Jews. As in all his writings, Wiesel tells us nothing of the facts, but reveals a lot about himself–and Jews in general.

For your information, the news outlet to which Wiesel offered his essay (for $25,000?) is a self-described e-paper that goes by the name of The Algemeiner. It is a Jewish-Israeli operation with 50 Jewish writers featured—and not a Gentile in sight. The Algemeiner even uses the Hebrew date (for example 1 Nisan 5772) at the top of their page.

Let’s now turn to the essay itself. First I will copy the essay as it appeared; then I will go through it sentence by sentence, commenting on the meaning.

Exclusive by Elie Wiesel: The Tragedy in Toulouse March 21, 2012

Will the hatred of the Jews ever finally vanish? Will Jewish children always be in danger?

This time, a murderer slew four Jews: a teacher and three young children.

When a blood-thirsty Jew-hater wants to kill Jews, he goes first to the Jewish schools. Jewish children are his primary target.

It’s always been this way. This is what Pharaoh, King of Egypt did, what Hitler did. And this is what happened now.

This is the background to the tragedy that occurred in the French city, Toulouse.

I have visited that city many times. The Jewish community there is old and well-established – it dates back to the Middle Ages – but it is dynamic.

In the streets, you can see Jews wearing yarmulkas. Nobody thinks of anti-Semitism. Spiritually, it is one of richest Jewish communities in France.

Obviously, the terrible murderous attack evoked tears and rage among both Jews and non-Jews. The President, his ministers, and other political figures in France, as well as all the newspapers, have demanded that the murderer be found and punished.

It often happens like this. Jewish blood is spilled and, temporarily, sympathy for Jews grows; the world warms to them.

But the pain does not go away, nor does the anger. We think about the martyrs: Rabbi Yochanan Sandler, his sons Aryeh and Gavriel, and Miriam Monsonego. We say, as is Jewish tradition: “May G-d avenge their blood.” That will be the response from Above.

Our own answer must be concrete and to the point. When we are persecuted, our response must be: We will remain Jewish – and do everything to become more Jewish.

Now my commentary in blue. Wiesel writes:

Will the hatred of the Jews ever finally vanish? Will Jewish children always be in danger?

Wiesel has made a slip here by using the word “of.” Hatred of the Jews can mean hatred by the Jews as well as hatred for the Jews. I read it first as the Jew’s hatred. In any case, he means to set up “hatred for Jews” as the crime. He doesn’t mention “hatred of Algerians” even though three French Algerians were the first victims of the murderer, who himself was of Algerian origin!

This time, a murderer slew four Jews: a teacher and three young children.

Wiesel uses the Old Testament word “slew” as an artifice, to create a sense of history repeating itself—Jews being slain again and again.

When a blood-thirsty Jew-hater wants to kill Jews, he goes first to the Jewish schools. Jewish children are his primary target.

Wiesel uses more apocryphal language to simplify the Algerian down to “a blood-thirsty Jew hater.” If this man was blood-thirsty, what then are Jews when they bomb Palestinian schools and hospitals? Are the persons inside those buildings threatening them? Can they really say they’re acting in self-defense? Wiesel once again refuses to show any concern for those whom Jews kill. It’s amazing that he gets away with ignoring the terrible fate of Palestinian children, and other children throughout recent history, such as the hundreds of thousands of innocent ethnic German children who were killed before and after WWII.

It’s always been this way. This is what Pharaoh, King of Egypt did, what Hitler did. And this is what happened now.

Pharaoh and Hitler are the two rulers who “expelled the Jews” in a way that is most hateful to Jews. It’s not really surprising when one thinks about it, but still eye-opening that Wiesel links them together here. In the bible story, Pharaoh grew fearful of the Jews because of their power in his land; it was the same with Adolf Hitler, but Hitler did not “target” Jewish children. I doubt that Pharaoh did either, in spite of the stories. Jews have made up many stories about Hitler, but they are lies, defamation and forged and mislabeled photographs.

This is the background to the tragedy that occurred in the French city, Toulouse.

Wiesel is saying that Hitler and Pharaoh are the ‘background’ of this contemporary event. Jews think like this. The four Jews who were killed in this rather sporadic fashion have to be seen as connected to a long chain of purposeful persecution … they must be seen as part of an eternal holocaust … and the world must also see it this way.

I have visited that city many times. The Jewish community there is old and well-established – it dates back to the Middle Ages – but it is dynamic.

Jewish communities anywhere are of high value, Wiesel implies, and must be safe-guarded by all of us. Wiesel emphasizes how long Jews have been in that particular place in France to show that it means they belong there. The comparison comes to mind of how long Palestinians have been in Palestine, but the Jews don’t want them there because they want all the land for themselves. Why is it that Jews want to share in everyone else’s land, but cannot share their own, which was given to them on conditions they have not fulfilled.

In the streets, you can see Jews wearing yarmulkas. Nobody thinks of anti-Semitism. Spiritually, it is one of richest Jewish communities in France.

In spite of the fact that they have been in France since the Middle Ages, they are still a “Jewish community in France” not Frenchmen or a French community. That says a lot. The four Jews who were killed were flown immediately to Israel for burial, which tells us even more that this Jewish community does not consider itself French.

Obviously, the terrible murderous attack evoked tears and rage among both Jews and non-Jews. The President, his ministers, and other political figures in France, as well as all the newspapers, have demanded that the murderer be found and punished.

How often does a President, his ministers and politicians take a personal interest in solving a crime? This shows the power of the Jews in Europe, not love for them. Politicians and newspapers believe they have no choice when it comes to catering to the Jews in their country. This has been true ever since Jews came to control the money, banks and financial systems (think Goldman-Sachs), and Wiesel knows it.

It often happens like this. Jewish blood is spilled and, temporarily, sympathy for Jews grows; the world warms to them.

Wiesel believes in a spiritual eternal opposition to the Jews. Gentiles will never accept Jews as they are, he is saying … since Jews are a people who insist on being and remaining separate from all others while they live and flourish in others’ nations … often at the expense of the people of those nations. At the same time, he expects sympathy for Jews as a persecuted class. He expects special protection for them. And to non-Jews who don’t want to give Jews that special place and special protection, he points the accusing finger.

But the pain does not go away, nor does the anger. We think about the martyrs: Rabbi Yochanan Sandler, his sons Aryeh and Gavriel, and Miriam Monsonego. We say, as is Jewish tradition: “May G-d avenge their blood.” That will be the response from Above.

Vengence is the cornerstone of Jewish thought. While he adds that it should come from above, from G-d, he wants it to come. He knows that young Jews will hear him. Wiesel now wants to make new Jewish martyrs of these four victims.

Our own answer must be concrete and to the point. When we are persecuted, our response must be: We will remain Jewish – and do everything to become more Jewish.

Those are fighting words. Our separation, our apartness, will never end, he proclaims. Nor will our demand for special protection. Elie Wiesel remains always a Hasidic Orthodox Jew who reveres the Talmud, the Cabala, and all esoteric Jewish rabbinical texts. Therefore, he is comfortable expecting the impossible. Animosity toward their host populations is a constant for Jews. Their crime against us is that they paint it the other way around. In this little essay, Wiesel provides another example of just how it’s done. … how we are convinced that it is our failings, not theirs. That’s why I have analyzed it in so much detail. Gentiles should take heed and reject Wiesel’s image of us … and reject him.

11 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: Algemeiner, Elie Wiesel, French of Algerian Origins, Jewish supremacy, Jews, Toulouse,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Wednesday, March 7th, 2012

By Carolyn Yeager

copyright 2012 Carolyn Yeager

Elie Wiesel questioned under oath in a California courtroom in 2008:

Q. And is this book Night that you wrote a true account of your experience during World War II?

A. It is a true account. Every word in it is true.

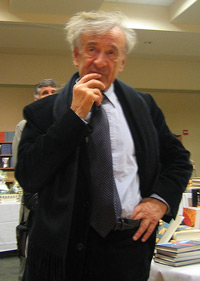

Elie Wiesel manning his table at a Jewish book fair in Austin, TX, 2006. The new translation of Night by his wife Marion had come out in January of that year, and it was immediately chosen for Oprah Winfrey’s book club.

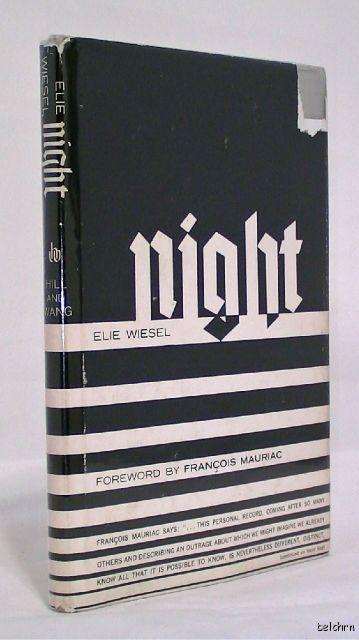

In Part One, I established that the decision to rebrand Night into an autobiography was the reason for a new translation, in which necessary changes could be made to better ‘fit’ the story both to the real Elie Wiesel and the known facts of the Hungarian deportation.

When the 2006 translation came out, with its new classification to “autobiography,” questions arose from some circles. Responding to these questions, Edward Wyatt wrote an article in the NewYork Times on Jan. 19, 2006, in which he quoted Jeff Seroy, senior vice president at Farrar, Straus & Giroux, parent company of Night publisher Hill & Wang, as strongly denying that changes were made to bring the book more in line with the facts. “Nonsense,” said Seroy. “Some minor mistakes crept into the original translation that were expunged in the new translation. But the book stands as a record of fact.”

Blaming the Translator

“Mistakes in the original translation” can only mean mistakes by Stella Rodway, the original translator! But we have already shown that Stella Rodway faithfully reproduced the French La Nuit, which was Wiesel’s own work. The author and publisher are casting these changes as translation errors to divert attention away from Elie Wiesel’s own errors—part of their campaign to pass Night off from now on as “a record of fact.”

Publisher Jeff Seroy, center, with writer Brad Gooch to his left, Doug Stumps on his right .

A record of fact it isn’t

When I ended Part One, Eliezer and Father were still in the train car on their way to Buchenwald. You will recall that the Yiddish, the French and thus the original English version of Night specified the trip took 10 days and 10 nights from Gleiwitz (on the former German/Polish border) to Buchenwald. Since we know from standard historical sources1 that the prisoners were evacuated from Monowitz on Jan. 18 and arrived in Gleiwitz the next day, Jan. 19; and since according to the description in Night itself, they spend three days in Gleiwitz (Jan. 20-22), this would make their day of arrival February 1, 1945. But in Night, Father’s death takes place the night of Jan. 28-29, three days before they arrived! This is why Marion Wiesel removed the number 10 in her new translation, leaving the number of days and nights undetermined.

A strange detail that actually belongs in Part One is on page 87 of the original Night. Eliezer remarks, after his and his Father’s deliberations and final decision to go on the march: “I learned after the war the fate of those who had stayed behind in the hospital. They were quite simply liberated by the Russians two days after the evacuation.” The evacuation, as we all know, was on the 18th. We also know the Russians did not arrive on the 20th of January! The actual liberation day is January 27. What possessed Wiesel to write this? Well, because it was in Un di velt: “Two days after we had left Buna, the Red Army occupied the camp. All the sick had stayed alive.”

From the point in the story of Eliezer and Father’s arrival at Buchenwald there are no significant changes made by Marion Wiesel to the original French and English versions. But there is much in all the versions that differs strikingly from the “official holocaust history” as written by acknowledged official chroniclers such as Danuta Czech. So I will continue with comparisons between Night and “official history,” along with some very significant changes made from Un di velt hot geshvign to Wiesel’s edited French La Nuit.

Arrival at Buchenwald: 26 Jan. or 1 Feb.?

Danuta Czech, in her Auschwitz Chronicle1, records that on January 26,

Danuta Czech, in her Auschwitz Chronicle1, records that on January 26,

A transport with 3,987 prisoners from Auschwitz auxiliary camps reaches Buchenwald. There are 52 dead prisoners in the transport. 115 prisoners die on the day of arrival. Their corpses are delivered to the autopsy room. (P 801)