Archive for the ‘Featured’ Category

Monday, November 15th, 2010

By Carolyn Yeager

copyright 2010 carolyn yeager [updated 12-5-15 and 2-6-25]

Is Elie Wiesel lying about having enrolled at the Sorbonne University in Paris? Or is he a victim of confused memories?

Elie Wiesel wrote the following in his memoir (1) published in 1995:

With Francois’s help I enrolled in the Faculty of Letters of the Sorbonne. At last I found my vocation.

I have happy memories of my student years. There were lectures by Daniel Lagache in the Descartes or Richelieu amphitheater, and by Louis Lavell at the Collège de France. (2) I devoured books on philosophy and psychology, Plato’s dialogues, Freud’s analyses. I wandered from bookstore to bookstore, from park to park. I remember the silence of the Sainte-Genevieve Library [not at the Sorbonne] and the chance encounters and inevitable rendezvous in the Sorbonne courtyard. Francois, my tutor, guide, and friend, did his best to initiate me into the life of the Latin Quarter, taking me to hear Sartre and Buber, whose lecture on religious existentialism was an event. The hall was packed, the audience enthusiastic. Buber was treated like a prophet. His listeners were elated, conquered in advance, ready to savor every word. There was just one problem. Had Buber spoken in Hebrew, Yiddish, English, or German, there would have been some people in the hall able to follow his address. But he opted for French, and his accent was so thick no one understood him. Everyone applauded just the same. No matter, they would read the text when it was published. But I was delighted to have seen the handsome face and heard the searching voice of the author of I and Thou, one of the great Jewish spiritual thinkers of our time.

According to the book’s index, this is the only page on which the word “Sorbonne” is found in the entire book of 418 pages—twice on page 154. The above is all Wiesel has to say about his “student years” at this historic and revered institution of higher education. Yet in spite of its paucity, this paragraph is seemingly all it has taken for the majority of Elie Wiesel’s followers, biographers, interviewers, and promoters to repeat it without question, as I will show further on.

Wiesel gives no dates for what would be something of a milestone in his life, either—as is in keeping with his penchant for “free-floating memories.” The last date he gives that refers to his own actual life at the time, is way back on page 120: “Fortunately, in 1947 the OSE arranged for a young teacher, Francois Wahl, to give me private lessons.” He says more on the next page, 121:

In 1947, as the underground war raged in Palestine, Francois performed important secret tasks for a Jewish resistance group . The following year our paths diverged. Later, much later, they would cross again.

It was in 1947 that Shushani, the mysterious Talmudic scholar, reappeared in my life. For two or three years he taught me unforgettable lessons about the limits of language and reason, about the behavior of sages and madmen, about the obscure paths of thought as it wends its way across centuries and cultures.”

Francois was only one of many revolutionary Jewish “terrorists” Wiesel was associated with during this period. But more important to our theme is that it seems a strange juxtaposition for Wiesel to claim he is learning about the “limits of language and reason” from the most important teacher in his life (Shushani), by his own admission, while being an enrolled student taking courses at the Sorbonne University. The French Academy has always been known for putting great store in language and reason! We are left with another big contradiction in Elie Wiesel’s life story.

Other reasons to be skeptical of Wiesel’s claim

Prof. David O’Connell, a professor of French at Georgia State University, has written unambiguously that Wiesel was never enrolled at the Sorbonne:

Despite his claims over the years about having studied philosophy and psychology at the Sorbonne and doing a two year internship at the Hôpital Sainte-Anne in clinical psychology,(3) he actually never enrolled for any credit-bearing course at the Sorbonne, or any other branch of the University of Paris. Even worse, there is no evidence that he ever earned a French secondary school diploma. Yet, he now earns a huge six-figure salary per year as a Mellon Professor of Literature at Boston University, a position that theoretically requires a Ph.D.(4)

After O’Connell’s article was published in 2004, neither Elie Wiesel nor the Sorbonne University provided any evidence to the contrary. Searching for a clue on the Internet, I came only upon evidence of the well-known Internet trend (5) of copying from other sites and sources without the slightest direct research being done. What I did not find was anything from Elie himself, in speeches, writings, interviews, about his “happy years” as a student at the Sorbonne, or anything to do with his education. In the examples listed below, the original source from which the information came is not given, nor is it known in most cases, because it was doubtless copied from someone who copied it from somewhere else. In some cases, the 1995 memoir may have been the source, but it was never cited.

Google Search on Elie Wiesel + Sorbonne:

In 1948, Wiesel enrolled in the Sorbonne University where he studied literature, philosophy and psychology. He was extremely poor and at times became depressed to the point of considering suicide. http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/biography/Wiesel.html

After the liberation of the camps in April 1945, Wiesel spent a few years in a French orphanage and in 1948 began to study in Paris at the Sorbonne. http://xroads.virginia.edu/~cap/holo/eliebio.htm

In 1948, Elie began to study literature, philosophy, and psychology at the Sorbonne in Paris. http://www.thefamouspeople.com/profiles/elie-wiesel-13.php

Elie lived in a French orphanage for a few years and in 1948 began to study literature, philosophy, and psychology at the Sorbonne in Paris. http://www.gradesaver.com/author/elie-wiesel/

Where did Elie Wiesel Study? After the war, he studied at the Sorbonne. http://answers.encyclopedia.com/question/did-elie-wiesel-study-101042.html

Elie Wiesel studies at the Sorbonne in Paris. He becomes interested in journalism. http://www.inthefootstepsofeliewiesel.org/about-elie-wiesel.html

In France, Elie Wiesel resumed his Jewish studies, eventually attending the Sorbonne to become a journalist http://www.inthefootstepsofeliewiesel.org/film-locations.html

Elie Wiesel: A Religious Biography by Frederick L. Downing. “With the help of his French teacher, Francois, Wiesel enrolled at the Sorbonne. He took classes on Plato and Freud and wandered through the bookstores.” http://books.google.com/books?id=GzdKZklZ2UIC&pg=PA77&lpg=PA77&dq=Elie+Wiesel+Sorbonne&source=bl&ots=jADPVye9CO&sig=bCo4TwonO3oMzIGQyp6yxzaGePY&hl=en&ei=Mz_bTLzyMsaPnwfOzskW&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=10&ved=0CFwQ6AEwCTgK#v=onepage&q&f=false

ElieWiesel: Spokesman for Remembrance by Linda N. Bayer. “As Elie’s teen years drew to a close, he enrolled at the Sorbonne, where he was quite happy.” http://books.google.com/books?id=IidC8iab6xgC&pg=PA67&lpg=PA67&dq=Elie+Wiesel+Sorbonne&source=bl&ots=In97QVm3I5&sig=YDs8oXNhf8gmUpmByHlsUeZQg3A&hl=en&ei=_kTbTLOcGNC9ngfX7IEX&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=10&ved=0CFoQ6AEwCTgU#v=onepage&q&f=false

After the war, Wiesel attended the Sorbonne in Paris and worked for a while as a journalist. http://www.litlovers.com/guide_night.html

1947 Elie Wiesel enters the Sorbonne in Paris. http://www.cliffsnotes.com/study_guide/literature/Night-Elie-Wiesel-Biography-Historical-Timeline.id-89,pageNum-7.html#ixzz14vnm6Bso

1948 Elie Wiesel studies at the Sorbonne in Paris. He becomes interested in journalism. http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/article.php?ModuleId=10007200

1952 After studying at the Sorbonne, Elie Wiesel begins travelling around the world as a reporter for the Tel Aviv newspaper Yediot Ahronot. http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/article.php?ModuleId=10007201

After learning French, Elie studied at the Sorbonne, a famous university in Paris. After he graduated [!! this writer got carried away – cy] Wiesel taught Hebrew and choir. He decided to become a journalist because of his life experiences. http://www.nobelpeacelaureates.org/pdf/ms_EliezerWiesel.pdf

Gary Hart, “Story and Silence” He had learned French and assumed French nationality by 1947 when he entered the Sorbonne. There he studied, among other things, philosophy and psychology. [Wiesel never became a French national – cy] http://www.pbs.org/eliewiesel/life/henry.html

Sent to Paris to study at the Sorbonne after several years of preparatory schools [Wiesel was not educated at a preparatory school –cy], he became a journalist for a small French newspaper, and supplemented his meager income as a translator and Hebrew teacher. http://www.pbs.org/eliewiesel/life/index.html

The Academy of Achievement: Wiesel mastered the French language and studied philosophy at the Sorbonne, while supporting himself as a choir master and teacher of Hebrew. http://www.achievement.org/autodoc/printmember/wie0bio-1

TIME magazine 1986: After the war Wiesel settled in France, where he studied philosophy at the Sorbonne http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,962649-1,00.html#ixzz14wFTUljN

Encyclopedia Britannica: After the war Wiesel settled in France, studied at the Sorbonne (1948–51), and wrote for French and Israeli newspapers. http://www.britannica.com/holocaust/article-9076939

Oprah! He studied literature, philosophy and psychology at the Sorbonne, http://www.oprah.com/omagazine/Oprah-Interviews-Elie-Wiesel

An analysis of Elie Wiesel’s exact words

From the single paragraph in his memoir, we can extract only one sentence that describes something unique to being a student.

I have happy memories of my student years. There were lectures by Daniel Lagache in the Descartes or Richelieu amphitheater, and by Louis Lavell at the Collège de France.

[Image: Richelieu amphitheater]

First, he says he was a student for “years,” which means at least two. The Descartes and Richelieu amphitheaters are large lecture halls where the professors give their lectures to students enrolled in their course. Daniel Lagache held the chair of psychology at the Sorbonne beginning in 1947; during the war he was active in the Resistance and had been imprisoned. This would make him especially attractive to Wiesel. I believe that one could manage to attend lectures when there was space without being enrolled in the course. Note that Wiesel carefully writes “There were lectures …”, not anything suggesting he was a student of Daniel Lagache.

At the Collège de France, which was not the Sorbonne, lectures were open and free to the public. Louis Lavell was a religious philosopher recognized as a forerunner of the psychometaphysic movement.

Conclusion: If Wiesel were a real student at the Sorbonne for at least two years, it’s a certainty he would have more to say about it than that he remembers lectures given by one professor in the amphitheaters. What was his course of study, who were his teachers, how much time did he spend studying and what kind of grades did he get? Who were his fellow students?

Instead, he substitutes that he “devoured books” of an assorted nature, which only means he read a lot. He “wandered” among bookstores and parks. He “remembers the silence” of a library [the Sainte-Genevieve, which is not at the Sorbonne] and “chance encounters” in the Sorbonne courtyard. This all sounds enchanting, but it doesn’t sound like a hard-working student … and he would have had to work hard at that university.

The rest of what he wrote, in spite of his remembering Freud and Martin Buber, is just more open lectures, now in the Latin Quarter. This is the description of a dilettante taking advantage of what was available in the great city, picking and choosing what interested him, not fitting into any strict discipline of real schooling. There is no doubt in my mind, under our present knowledge, that he was not a student; thus it’s no wonder he remembers his “student years” in Paris as happy; he was basically doing as he wished. Remember, he was a student of the mystic Shushani during this time.

What we find in this instance is totally reminiscent of the single paragraph by which he described in his memoir another important undertaking in his life—the writing of his first manuscript after his 10-year vow of silence [Or was it actually nine years? He jumped the gun by one year, according to his memoir]. The reason he has so little to say? It’s pretty obvious it is because there was nothing there for him to remember.

But these few lines in his 1995 memoir cannot be the origin of the belief that he was educated at the Sorbonne, because Time magazine wrote in 1986, after Wiesel was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, that “After the war Wiesel settled in France, where he studied philosophy at the Sorbonne…” Where did Time magazine get that information? What is the earliest source of it? It would be interesting to know this, but it’s not essential because we know that Wiesel’s own brief mention, written in 1995, is not convincing. Thus any earlier mention of it would not be convincing either.

Has damage control on the Sorbonne question begun?

Here is another odd fact.

On Elie Wiesel’s Wikipedia page, there is no mention of his attending the Sorbonne University, let alone being enrolled there–or at any school or university. Yet, it was previously there and has been removed. It currently says:

After World War II, Wiesel taught Hebrew and worked as a choirmaster before becoming a professional journalist. He learned French, which became the language he used most frequently in writing. He wrote for Israeli and French newspapers, including Tsien in Kamf (in Yiddish) [and] L’arche.(6) [Both are Jewish newspapers, the first being Zion in Kamf in English -cy]

But on the previous Wikipedia page found at : http://web.archive.org/web/20080804112451/http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elie_Wiesel dating from Aug. 2008, found at a web archive, it was there. [See comment #1 below.] And I think it was there up to 2010; during this year the page was updated. It read:

After the war, Wiesel was placed in a French orphanage, where he learned the French language and was reunited with both his older sisters, Hilda and Bea, who had also survived the war. In 1948 he studied philosophy at the Sorbonne.

Why was it removed? Only one reason: Because someone at Wiki, or someone who can direct someone at Wiki, knows that Elie Wiesel did not study at the Sorbonne, and they would like it to appear that they never said he did. This is what is called Rewriting History because it’s done without telling readers what has been changed, and why.

A serious charge? Or do many of you accept it without complaint? Many of us know that the life history of Elie Wiesel was partly made up to begin with, so adding and subtracting parts of it, as research into his life uncovers some of the lies, may simply appear understandable damage control.

Yet, what about the “why”? Whose bright idea was it to pretend that Wiesel had “studied” at a famous university rather than tell the truth that he has never been a registered student since he left his hometown in Sighet at age 15. We have to believe that Wiesel himself began saying and implying this to give himself better credentials. He has never disputed it or set the record straight. Therefore, until we hear from him, we have to conclude that Wiesel thinks nothing of committing fraud – while he constantly points the finger of blame to so many of the rest of us.

The Wikipedia page for his book Night still mentions the Sorbonne:

From 1947–1950, he studied the Talmud, philosophy, and literature at the Sorbonne, attending lectures by Jean-Paul Sartre and Martin Buber.(7)

[That also has been removed from this Wikipedia page. cy -2025] It appears to be taken from his memoir, but is confusingly written, no doubt purposefully. Confusion abounds around the narrative of the life of Elie Wiesel, as this entire website Elie Wiesel Cons The World shows. You’re probably already familiar with the quote of Wiesel to the Rebbe that some things are true that never happened and vice versa. On another occasion Wiesel revealed how his mind works. This is from Elie Wiesel: Conversations by Elie Wiesel and Robert Franciosi. Wiesel responds to a question about one of his books:

In this book “One Generation After” there is a sentence which perhaps explains my idea: “Certain events happen, but they are not true. Others, on the other hand, are, but they never happen.” So! I undergo certain events and, starting from my experience, I describe incidents which may or may not have happened, but which are true. I do believe that it is very important that there be witnesses always and everywhere. (8)

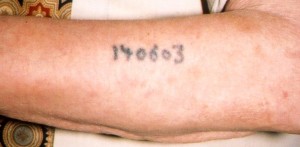

From this, the reader can judge for him/herself what kind of a witness Elie Wiesel is. We can understand that “certain events” he experienced during the war gave him ideas to “describe incidents which didn’t happen” but could have happened and so are true in his mind. This exactly explains how he can say “every word is true” and “I have a tattoo on my arm.” My judgment is that Wiesel really missed out by not getting an education at the Sorbonne, which might have grounded him in reason and precise language. As it is, he lives in a mystical realm wherein things are true because he says they are … leaving him satisfied, his peace undisturbed.

Endnotes:

1. Elie Wiesel, Memoirs: All Rivers Run to the Sea, Alfred Knopf, 1995, pp. 154-55.

2. Collège de France is a separate institution across the street from the historical campus of La Sorbonne at the intersection of Rue Saint-Jacques and Rue des Ecoles […] What makes it unique is that each professor is required to give lectures where attendance is free and open to anyone, even though some high-level courses are not open to the general public. The motto of the Collège is “It teaches everything;” its goal can be best summed up by Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s phrase: “Not preconceived notions, but the idea of free thought.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coll%C3%A8ge_de_France

3. Updated Dec. 2. Prof. O’Connell says that Wiesel made this statement in his interview book with Brigitte-Fanny Cohen entitled Qui etes-vous, Elie Wiesel?, Lyon, La Manufacture, 1987, p. 63: “For two years, every morning, I took classes at the Hôpital Sainte-Anne and observed the patients.” Please read Prof. O’Connell’s comment below [#3] and my reply. A portion of this interview was included in Elie Wiesel: Conversations, ed. by Robert Franciosi, University Press of Mississippi, 2002.

4. “Elie Wiesel and the Catholics,” Culture Wars magazine, Nov. 2004. Online at http://www.culturewars.com/2004/Weisel.htm

5. This phenomenon is not limited to the Internet; historians also quote from the published work of other historians without knowing the truth of it. It’s enough for their source to be from a recognized scholar or writer from a recognized university.

6. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elie_Wiesel#cite_ref-11

7. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Night_(book)

8. http://books.google.com/books?id=Ym8KcrzUZKYC&pg=PA32&lpg=PA32&dq=Elie+Wiesel,+Sorbonne&source=bl&ots=nahRgAmiLz&sig=PP17IzP9fhIZMFRfEg0sAWfpwDE&hl=en&ei=eSPbTK3CAZT0tgOfkqSaBw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=8&ved=0CFIQ6AEwBw#v=onepage&q=Elie%20Wiesel%2C%20Sorbonne&f=false

7 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: All Rivers Run to the Sea, damage control, Descartes and Richelieu amphitheaters, Sorbonne,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Monday, November 8th, 2010

The following news release has been sent to Boston, MA and Orange County, CA campus and regular media, and to selected Internet sites. It will also be mailed to students at BU and CU, where Elie Wiesel holds positions as a teacher. This is a major effort on our part, and we ask the assistence of our readers to publicize this extraordinary event, with all its hope for the exercise of free speech and the removal of taboos.

“A Question of Ethics” Essay Contest announced for Boston and Chapman University students; $1000 in prizes

We are pleased to announce the first East Coast—West Coast “A Question of Ethics” Essay Contest for students enrolled at Boston University in Massachusetts and Chapman University in Orange, California.

The winning essay will be awarded $500; second prize will receive $250; two honorable mentions $125 each. The winning essays will be published on the web site Elie Wiesel Cons The World.

The essays must analyze one or more ethical issues surrounding Elie Wiesel as they are presented on the pages of the website Elie Wiesel Cons The World. These issues may include [not in order of importance]

- Prof. Wiesel’s refusal to show his claimed tattoo.

- The documents from Buchenwald that do not support Wiesel’s presence there.

- His claim to be in the famous Buchenwald Liberation Photo when, according to his book, he was deathly ill in the hospital at the time.

- His close association with the Irgun terrorist gang in the late 1940’s.

- The questions surrounding the authorship of his first book, Un di Velt Hot Gesvign, allegedly 866 pages written in less than two weeks while on a ship crossing the Atlantic.

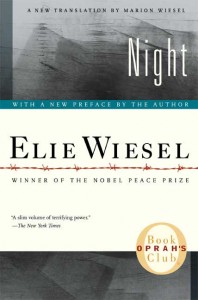

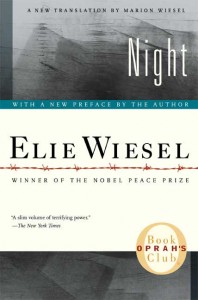

- The insistence that his book Night, read by school children all over the world, is a factual account of his experience at Auschwitz and Buchenwald.

Though the essays must utilize the information made available on Elie Wiesel Cons The World, information from other sources is acceptable as additional material. Our objective is for the essayists to examine the ethics challenges facing Prof. Wiesel in light of the information we have provided at our website.

Deadline for essays to be received is Feb. 1st, 2011. To be considered for a prize, essays must be a minimum of 500 words. Proof of registration as a student at Boston or Chapman University must accompany the essay. This can be a copy of one’s current semester course registration along with a University ID card. Manuscripts should be emailed to [email protected] with the subject line: Ethics Essay Contest.

Contact:

Carolyn Yeager

c/oCODOH, PO Box 439016

San Ysidro, CA 92143

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.eliewieseltattoo.com

Saturday, November 6th, 2010

FYI: This is an example of an all-propaganda, no-forensic information “news article” that has been copied by AFP from a “News Release” sent out by the Elie Wiesel National Institute for the Study of the Holocaust in Romania. Photograph and all. They publish it “as is” without checking facts. Notice there is no author for this story; no journalist wrote it. The article below appeared in the Montreal Gazette on Nov. 5. The Montreal Gazette seems to be a news outlet specially partial to Israel and Jewish propaganda. I have added my comments ~CY.

MASS GRAVE OF VICTIMS UNEARTHED IN ROMANIA

AFP November 5, 2010

Human remains are seen after archaeologists uncovered a mass grave of Jews killed by Romanian troops during World War Two in a forest area near the village of Popricani, close to the city of Iasi, in northeast Romania.

Human remains are seen after archaeologists uncovered a mass grave of Jews killed by Romanian troops during World War Two in a forest area near the village of Popricani, close to the city of Iasi, in northeast Romania.

Photograph by: Anthony Cioflanca, Elie Wiesel National Institute for the Study of the Holocaust in Romania.

[Comment: Notice that Cioflanca is employed by the EW Nat. Inst. in Romania. He is the only “archaeologist” mentioned and does not seem to be a real archaeologist. If he were, his credentials would be given. Therefore, who are these archaeologists that uncovered the grave?]

BUCHAREST – A mass grave containing the bodies of Jews killed by the Romanian army during World War II has been discovered in a forest in northeastern Romania, the Elie Wiesel National Institute said on Friday.

[Comment: It’s not been forensically determined that they are Jews; they are being called Jews based on “talking to locals.”]

“So far we exhumed 16 bodies but this is just the beginning because the mass grave is very deep and we only dug up superficially”, Adrian Cioflanca, the researcher at the origin of the find, told reporters during a press conference.

[Comment: They say they have 16 “bodies,” but they claim 100 before they ever find them.]

The Elie Wiesel National Institute for the Study of the Holocaust in Romania and Cioflanca both said they believe up to 100 bodies could be buried in the mass grave.

The find, in the Vulturi forest in Propricani, about 350 kilometres (220 miles) northeast of Bucharest, is “further evidence of the crimes committed against Jewish civilians in Romania”, Elie Wiesel institute head Alexandru Florian said.

“It is another testimony of a shameful period in Romania’s history”, Aurel Vainer, representative for the Jewish community at the lower house of parliament said.

[Comment: Two quotes solely of propaganda value from two political, activist Jews pointing the finger at Gentiles before the evidence can be studied. This is the formula that we have seen used over and over.]

According to an international commission of historians led by Nobel Peace laureate Elie Wiesel, himself a Romanian-born Jew, some 270,000 Romanian and Ukrainian Jews were killed in territories run by the pro-Nazi Romanian regime during 1940-1944.

[Comment: Now we come to the blanket statement of distorted historical “truth.” When did Elie Wiesel become a historian? He is not. Where does the figure of 270,000 Romanian and Ukrainian Jews come from? What “international commission” is being referred to?]

This is the first time a Holocaust-era mass grave has been discovered since 1945, when 311 corpses were exhumed from three locations in Stanca Roznovanu, close from Iasi, according to the Wiesel Institute.

[Comment: No wonder they are trying to make a big deal of it. They need to come up with something after 65 years of nothing but “witness testimony.”]

“For a long period of time, no research was done because the subject was taboo under the communist regime (1945-1989) and also for some years after the return of democracy in 1989″, Cioflanca told AFP.

[Comment: Just think how tough the communist regime of ‘45-’89 made it to get any truth for Germans. The taboo in place by the Holocaust enforcers up till this very minute makes it very difficult to disseminate any truth for German losses, and who the true perpetrators were. Democracy is of no avail in their case.]

[NOTE: From an updated AP report in the Kansas City Star, we read: “Romania’s role in the Holocaust remains a sensitive and highly charged topic. During communist times, the country largely ignored the involvement of Romania’s leaders in wartime crimes.” If this is the case, it’s very likely the Communists did the killing, not Romanian “Nazis.” But it is in the interest of the Elie Wiesel Institute on the Holocaust in Romania to blame the “Nazis” and “fascists” in order to bolster “Holocaust” claims, if at all possible. Naturally, the current Romanian regime will go along with that. The Jews will cause them endless trouble if they don’t; Germans and Romanians will not say a word. To get to the bottom of the events that are behind the discovery of these bones would take an honest, careful investigation by neutral scientists — which is not what we’re seeing here.]

Things improved after the Wiesel-led commission’s report in 2004 and in 2006 president Traian Basescu called on his fellow countrymen to face up to the role played by the pro-Nazi regime of wartime Romanian dictator Ion Antonescu.

The mass grave in Propricani was discovered after Cioflanca, a historian, gathered testimonies of local inhabitants who saw the killings of Jews. One of the witnesses escaped after convincing the Romanian troops that he was an Orthodox Christian, Cioflanca said.

[Comment: Now Cioflanca is called an historian; previously he is called a “researcher” and also an “archaeologist.” But his actual credentials are never given. What are they? Because he “gathered testimonies of local inhabitants” – this qualifies him as an historian?]

The victims could be Jews from the northeastern city of Iasi, where Romanian officials and military units, assisted at times by German soldiers, killed at least 8,000 during a pogrom in 1941, according to figures by the U.S. Holocaust memorial museum.

[Comment: This is another blanket statement. The USHMM is not a credible, unbiased institution, but the product of Holocaust survivors, the Holocaust Industry, Jewish organizations, and Jewish influence in and on the US Govt. Their “figures” are meaningless without independent research and scrutiny.]

Many of them are buried in official common graves.

The researchers will now try to identify the bodies excavated.

“We will not be able to use DNA tests because we do not have any contact with potential relatives still alive and, to use DNA, you need to compare samples,” Cioflanca said.

[Comment: No relatives? What about the witnesses who saw what took place – they don’t know who any of them were? What about the one who escaped? Do they not want to use DNA because it could show these are not Jewish bones at all, but Romanian or some other. Notice how they don’t even consider that they might not be Jews. They want them to be Jews. The more dead Jews it can find, the happier the Elie Wiesel Institute is!]

The exhumations are expected to go on after consultations with the authorities.

[Comment: “Consultations” means pressure, bribery, threats of a political and financial nature. In other words, “we’ll destroy your careers if you don’t go along with us, and we’ll do all in our power to blacken Romania’s reputation and standing in the European Union.”]

The military prosecutor’s office has opened an investigation.

[Comment: [Will this be a real investigation or one run by the Jewish “archeologists” and “historians”? A necessary question.]

After the find, the Elie Wiesel Institute deplored the fact that some Romanian cities, like Sibiu, Pitesti and Timisoara, “still continue to celebrate the memory of Romanian officials who were war criminals and who took part in the persecution against Jews by giving their names to streets.”

[Comment: Ah, Elie. His heart still full of revenge for those “war criminals” who dared to lay a hand on a Jew. That a Romanian official should have his name on a street!! Make them all Jewish names as a proper memorial to their unique suffering; then Elie Wiesel might be satisfied.]

© Copyright (c) The Montreal Gazette

1 Comment

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: Elie Wiesel Natl. Inst. for the Study of the Holocaust in Romania, mass grave, Romania,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Friday, October 29th, 2010

by Carolyn Yeager

Elie Wiesel will “spend time” at Chapman University in Orange, California beginning this spring and for the following four years, through 2015, according to Chapman President Jim Doti. Wiesel has been appointed as a “Distinguished Presidential Fellow”, which means he will visit classes in Chapman’s Holocaust history minor, and possibly other disciplines, including history, French, religious studies and literature, according to chapmannews.

Chapmannews reports that complete plans for his fellowship activities are still in progress (as of August) and that he will retain his full-time faculty position at Boston University. As we have pointed out on this website, Wiesel’s duties at BU are light, leaving him time for his extra-curricular activities, now including being employed by a second university. However, Wiesel’s fellowship stay is also described as amounting to only “several days each spring.” My! “Visit” is certainly the right word for it.

“Distinguished Presidential Fellow” may be a newly invented position, meaning that he is appointed by the President (Jim Doti), not hired under academic requirements by a department dean. Wiesel will be what you might call, in diplomatic terms, an at-large representative of the Jewish interests that are no doubt paying his salary. He will be most closely associated with Chapman’s Rodgers Center for Holocaust Education, a unique construction that bridges the Religion and History Depts, and was opened in Feb. 2000 “through a generous gift from Barry and Phyllis Rodgers, [and] dedicated to preparing young people to become witnesses to the future.” Witnesses of the Holocaust? Is this the job of a university? Well, it seems to depend on who offers the money, and what they want it to be used for.

Wiesel offered special words of praise to Dr. Marilyn Harran, who directs the Rodgers Center for Holocaust Education, for “the way in which the university is teaching and remembering some of the most tragic events in human history, events that have had such a deep influence upon my life.” She and the Center are the reason that Wiesel says he “made the decision to return to Chapman annually as Distinguished Presidential Fellow.”

Dr. Harran is a professor of both history and religious studies at Chapman. She has even stronger words of praise for Wiesel, announcing, “[he] has been the face and voice of Holocaust memory and witness to the world, and an ambassador of humanity and hope for decades. He has consistently challenged us to learn from the Holocaust and to reject indifference, and – in his words – ‘to think higher and feel deeper.’ We are unbelievably fortunate that he has chosen to return to Chapman and to share with us his knowledge and wisdom. I am stunned and deeply grateful that he will be with us in this new role as Distinguished Presidential Fellow. I know our university community will be profoundly enriched and inspired by his presence.”

University President Doti is equally humbled by the presence of the great man, saying “That this remarkable individual, one of the world’s most famous and respected people, one who truly exemplifies the meaning of ‘global citizen,’ should choose to return to spend time with our students is truly a tremendous honor for Chapman.”

Does it seem from this that Wiesel will be under any kind of performance requirement at Chapman, or will he be the determiner of his own course of action? It is probably the same at Boston University – the tail is wagging the dog. But Wiesel’s presence at both universities is more a public relations benefit to the school than an educational benefit for students. His fame as a Holocaust icon, including his Nobel Peace Prize, make him a valuable commodity – as opposed to having any pretensions to scholastic stardom.

Chapman University is seeking to transition from a “teaching university” to a “research university.” That means the faculty will be required to “publish” in the field of their expertise, and the more you publish, the higher your pay. Not all faculty think this will be beneficial to the student experience at Chapman; there is a school of thought that values professors as mainly teachers rather than researchers. But others, probably more powerful, think it’s more important to “upgrade” Chapman into a higher-rated university.

Emphasis on the Holocaust

Elie Wiesel’s visiting fellowship may be in accord with those objectives. The Sala and Aron Samueli Holocaust Memorial Library opened in April 2005, dedicated to providing a space “where teachers and students may gather to learn from survivors, visual testimonies and printed resources.” At the entrance to this library is a large bronze bust of – guess who? Elie Wiesel!  The library has an exhibit area that currently displays “Themes of the Holocaust” featuring photos and artifacts donated or lent by individuals and institutions. Group tours are also arranged. It’s like a little Holocaust museum right there on the university grounds.

The library has an exhibit area that currently displays “Themes of the Holocaust” featuring photos and artifacts donated or lent by individuals and institutions. Group tours are also arranged. It’s like a little Holocaust museum right there on the university grounds.

At Chapman, the Holocaust is taught in both the Religion and History Depts., and several of the courses overlap both. It is really quite amazing how much of the History curriculum is devoted to this subject. That Holocaust is taught in the Religion Department—as it is at Boston University—makes sense because it is a belief. It has become an unquestioned, highly enforced belief system that is assumed to be true at its base, but with too little examination of the basic operations it would require.

A difference in approach at Chapman however, as compared to BU, is the emphasis on Holocaust in the History Dept. I discovered six courses containing Holocaust, five of them devoted exclusively to it. This is a lot for a small university like Chapman, perhaps more than at any other accredited university in the United States. The History Dept. offers on an every-year basis:

HIST 307 Germany and the Holocaust

(Same as REL 307.) This course examines the Holocaust within the context of the history of World War II. Topics include the origins of the Holocaust, the implementation of the Final Solution, resistance to the Nazis, survivor experiences, and the legacy of the Holocaust. (Offered every year.) 3 credits. Also offered in Religion

HIST 365 Topics in the Holocaust

(Same as REL 365.) This course examines selected topics within the study of Holocaust history, such as the roles of doctors, theologians and religion under Hitler, the persecution of non–Jewish groups (including homosexuals and gypsies), and the experiences and choices of perpetrators, victims, and bystanders. Courses that treat different themes may be repeated for credit. (Offered every year.) 3 credits. Also offered in Religion

HIST 365a Perpetrators, Witnesses, and Rescuers

[Same as REL365a] Within the context of Nazi Germany, World War II and the Holocaust, this course examines the choices that individuals faced and the decisions that defined them as perpetrators or rescuers. Includes the stories of those who survived the Holocaust to become witnesses to the truth. (Offered every year.) 3 credits. Also offered in Religion

Offered every other year, Spring semester:

HIST 365b The Holocaust: Memoirs and Histories

This course explores the complex history of the Holocaust from the perspective of selected memoirs written by survivors and examines the contributions and limitations of memoirs in shaping the historical record. (Offered spring semester, alternate years.) 3 credits.

The following two courses are offered “as needed:”

HIST 356 Modern Germany: From Sarajevo to Stalingrad

This course examines the political, social, and intellectual history of Germany from World War I to the end of World War II. Topics include the Holocaust and the roles of individuals in taking Germany down the path to two world wars. (Offered as needed.) 3 credits.

HIST 297 The Holocaust in History and Film

An introduction to the history of the Holocaust, from initial persecution to the implementation of the Final Solution, including the actions of perpetrators, rescuers, and resisters; the dilemmas facing those targeted for persecution, and major issues in the interpretation and visual representation of the Holocaust. (Offered as needed) 3 credits.

* * *

The Religion Dept. at Chapman offers three courses every year that are also offered in History:

REL 365 Topics in the Holocaust

(Same as HIST 365.)

REL 365a Perpetrators, Witnesses, and Rescuers

(Same as HIST 365A.)

REL 307 Germany and the Holocaust

(Same as HIST 307.)

In addition to all of this, there is the extensive program offerings of the Rodgers Center for Holocaust Education, which is entirely funded by several Jewish groups outside the university. According to the Chapman website, the mission of the Rodgers Center is to increase knowledge of the Holocaust, further discussion of the causes of genocide, and encourage reflection on the contemporary relevance of the Holocaust to our lives today.

As part of its mission, the Center sponsors a Lecture Series each year. For example, on Sept. 21 James Young gave a lecture entitled “Stages of Memory: Challenges of Memorialization (sic) from the Holocaust to the World Trade Center.” Young is Professor of English and Judaic Studies at the U of Mass, Amherst. He has written two books about the Holocaust: one about Holocaust Memorials and one about Holocaust Architecture. [Isn’t Holocaust to the World Trade Center quite a stretch? -cy]

The Art and Writing Contest is an annual program that involves “thousands of Southern California middle and high school teachers and students, culminating in an awards ceremony on campus.

Beginning in 2000, the Rodgers Center began a yearly Evening of Holocaust Commemoration to create a “community of witnesses” for the Chapman area.

What more can they think up?!

No one can deny that Holocaust is alive and well at Chapman University. And now Elie Wiesel, the “Grand Poobah” himself, will arrive every spring to energize it even further, and bring lots of media attention in his wake. This is a public relations dream!

But for those of us who care about the truth, it’s more like a nightmare. What do you think, dear reader?

4 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: Chapman University, Distinguished Presidential Fellow, Marilyn Harran, Rodgers Center for Holocaust Education, Sala and Aron Samueli Holocaust Memorial Library,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Tuesday, October 26th, 2010

by Carolyn Yeager

BU’s Dept. of Religion is extremely over-weighted with Jewish faculty and Judaism courses.

Elie Wiesel, as the Mellon Professor in the Humanities at BU, teaches in both the Depts. of Philosophy and of Religion. Both departments are contained in the College of Arts and Sciences, headed by Virginia Sapiro.

I took a look at the Dept. of Religion after a student at BU informed me in a helpful manner that our Elie Wiesel Cons The World Boston University Project page was wrong in stating that Prof. Wiesel was not teaching any courses during the fall 2010 semester. This student referred me to the Dept. of Religion course offerings which are online and which show Elie Wiesel as the instructor of two undergraduate courses for this current semester. [I have corrected our page.]

The fall semester continues until December and the year-end break. Wiesel is teaching two courses especially designed for him [or by him]: Literature of Memory 1 and Literature of Memory 2. What is interesting about these courses is that they cover solely Wiesel’s own writings.

Lit of Memory 1 “examines the development of Elie Wiesel as a novelist from a selection of his fictional works. Particular attention is paid to the books’ structures, themes, and moral lessons. (It) provides an opportunity to study these works with the author himself.”

Lit of Memory 2 “explores Elie Wiesel’s non-fiction writing. Using his memoirs, Biblical interpretations, and reflections on prominent Hasidic masters, we seek to better comprehend the ethical voice in his work. (It) provides the opportunity to explore these issues with Professor Wiesel himself.”

It is obviously considered a special advantage for BU students to study at the master’s feet. I would certainly like to listen in on one of the class sessions myself! The Spring 2011 course offerings for the Dept. of Religion show no classes taught by Elie Wiesel. Perhaps he will be teaching a course for the Philosophy Dept. in the spring. As of this writing, they are not yet online.

In the BU Dept. of Religion I was amazed to find a large percentage of course offerings devoted solely to Judaism and Jewish culture. I would not have been surprised to find there were more than for any other religion, but the proportion was so wildly unequal one wonders how they get away with it. Here is the breakdown for the current semester. [Note: please see my reply to Dove in the Comments section below (11-13 at 8:55 a.m.) re a more complete listing of Religion Dept. courses for Fall and Spring, 2010-11, which you can find here. I’m not going to redo the article at this time because the ratio of Jewish courses to Christian and others remains essentially the same.]

Fall 2010 offers 24 lower and upper level courses, all 4 credit hrs

8 courses are solely about Judaism and Jews

- Elie Wiesel, Lit. of Memory 1 [his own fictional writings]

- Elie Wiesel, Lit of Memory 2 [his own non-fiction writings]

- Introduction to Rabbinic Literature

- Jewish Mystical Movements and Modernization

- American Jewish Experiences

- The Modern Jew

- The Holocaust

- Holocaust Literature and Film

1 course about Judaism and Christianity [Apocalyptic Lit in Early Judaism and Christianity]

1 course solely about Christianity [Gender in Medieval Christianity]

2 courses solely about Islam

1. Islamic Law

2. Islamic Theology/Philosophy

1 course about Daoism

1 course about Zen-Buddhism

1 course about Culture, Society and Religion in South Asia

9 courses on Religion—Non-Specific

This is an astonishing 36% about Jews and their culture/religion as opposed to about 25% for all non-Jewish religions combined, and around 39% for non-specific religion topics. And this is not in any way an exceptional semester, considering the same proportion appears in the spring semester.

Spring 2011 [click on “Courses” under Academics] offers 17 lower and upper level courses, all 4 credit hrs

6 courses solely about Judaism and Jews

- History of Judaism

- Classical Jewish Thought

- Gender and Judaism

- The Holocaust

- Jewish Bioethics

- Topics in Judaic Studies: The Zionist Idea

2 courses solely about Christianity

- Varieties of Early Christianity

- Theology of Christian Mysticism

1 course on Islam

1 course on Buddhism

3 courses on Religion & Literature from around the world

4 courses on Religion-Non-specific

Here again we see 35% solely about Judaism; about 24% on Christianity, Islam and Buddhism combined; 41% for non-specific religious topics. This seems to be the formula. What does it tell us about BU?

Has Boston University become a Jewish institution?

As we note on our Boston University page, according to Hillel.org and Reform Judaism Magazine [via Wikipedia; NOTE: the Wiki BU page has been revamped since July and all mention of Hillel House removed], “Boston University … has the second highest number of Jews of any private school [after New York University] in the country with between 3,000 and 4,000 [out of approx. 30,000], or roughly 15% identifying as Jewish.” It is also, according to the latest figures available, approximately “68% white, 15% Asian, 7% international students, 7% Hispanic, and 2% black.” While 15% Jewish is a high number in a country where the total Jewish population is no more than 2 to 2½%—it doesn’t begin to reach to the 35% average of Judaism courses offered by the BU Dept. of Religion.

First we might ask: Why is the Jewish student population at BU so high? One reason is the location in Boston, Mass. and surrounding states like New York and New Jersey, which have a higher than average Jewish population. Another is the culture that has developed there. Again, as we stated on our Boston University page, the school was historically affiliated with the United Methodist Church, but lost its Christian identity somewhere along the way and now describes itself as nonsectarian. However, considering its student body, and its faculty and administrative personnel, not to mention the Board of Trustees, it could very easily—and perhaps more correctly—be identified as a predominately Jewish institution.

When we look at the administrative faculty positions in the Department of Philosophy, we can’t help but notice the abundance of Jewish names. Nine out of 29 professors [31%] are unmistakably Jewish, and others could very likely be. In the Department of Religion, of 31 professors listed, eleven are unmistakably Jewish [35%] and some others are likely Jewish. The Jewish professors teach the Jewish courses, so the percentages fit together.

I’m not going to look into BU in its entirety because I am not on a hunt to discover how many Jews are employed there [although I may be accused of that]. What I am after is to discover whether BU has a Jewish culture and political base, and it appears that it does. The more “Jewish” Boston University becomes, the more Jewish students are attracted to attend this university. And so it builds on itself. I can tell you that if you’re going to major in Religion, you’re going to get a heavy dose of Judaism.

And Holocaust, too. Along with Elie Wiesel as a celebrated professor there, I’d like to acquaint you with Prof. Steven T. Katz , who is Director of the Elie Wiesel Center for Judaic Studies at Boston University, and holds the Alvin J. and Shirley Slater Chair in Jewish and Holocaust Studies in the Dept. of Religion. [I didn’t know there was an Elie Wiesel Center for Judaic Studies at BU until I read Dr. Katz’ bio. I will have more to say about that in another blogpost.] Katz was also Chair of the Academic Committee of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum [in Wash. D.C.] for five years. He still serves on that committee, and is also Chair of the Holocaust Commission of the Memorial Foundation for Jewish Culture. Not surprisingly, he’s teaching the course “The Holocaust” jointly with the prolific Professor Hillel Levine. Katz is no doubt too busy to do more, as he is also one of the American representatives to the International Task Force on the Holocaust, established by the King of Sweden, now sponsored by the European Union.

Holocaust as part of the Religion curriculum at BU

It is left to us to figure out why BU is offering courses on The Holocaust in the Department of Religion, rather than in History. Strangely, when I look at the course offerings in the Dept. of History, the word “Holocaust” does not appear once. A course titled World War II: Causes, Course, Consequences is offered in the Spring 2011 semester. That is the only mention of WWII in all the course offerings for both semesters [not to mean it is not touched on in some other courses].

However, there are several courses about Israel and Jews for general students and history majors. Among the undergraduate courses for Fall 2010, there is Jews in the Modern World, Topics in the History of Israel, and Topics in Jewish History. For the Spring 2011 semester, I find The History of Israel: An Introduction, Topics in Jewish History, and The Making of the Modern Middle East [this one taught by Jewish professor David Fromkin]. This is more than it might look considering the entire spectrum of world history of all cultures that needs to be covered in a Dept. of History. Israel is a tiny state and Jews make up a tiny percentage of the world’s population, yet at BU they are given an inordinate amount of attention.

Is the Holocaust, as it is understood by most professors, an historical event or a religious event, according to Boston University? First let me say that the fact of the History Department remaining aloof from the Holocaust is not surprising at all. Real historians—trained scholars—stay away from the Holocaust because actual evidence for it is weak. It is based on war-time and post-war propaganda; witness testimonies by the alleged victim-survivors; photographs and confessions, many of which have been demonstrated to be fake; and poorly-explained happenings. Yet it is politically verboten to question it; therefore the answer for historians is simply to not teach, write or talk about it, but only to give it lip-service.

However, for Elie Wiesel [and those who surround him], the Holocaust is the mainstay of his entire career. Wiesel treats the Holocaust as a religion, complete with prophecies and forerunners, saints and heroes, highly embellished but un-provable narratives [including his own], and miracles given as explanation for that which can’t be explained otherwise. One of Wiesel’s continuing themes is that the Holocaust cannot be described, nor can it be understood by those who were not there.

Thus, it is in the interests of Professors Wiesel, Katz, Levine, and other Jewish proponents of “The Holocaust” to keep it in the Dept. of Religion. And this is where we find it. ~

NOTE (Oct. 27): On Monday night, Oct. 25, Elie Wiesel, as a Prof. of Religion at BU, gave the first of three lectures on Old Testament biblical themes to a reported 1000 students and faculty at Metcalf Hall on the BU campus.

The lecture was titled “In the Bible: A Judge Named Deborah,” about a female judge and prophetess of “Israel” who led a successful campaign against the Canaanites, the seemingly eternal enemies of “Israel” throughout the bible. The story is found in the book of Judges.

According to The Daily Free Press student newspaper, “Wiesel then spoke about Yael, the woman who killed the leader of the Canaanite army by hammering a peg through his head (!), and went on to argue that women played essential roles in the Bible, starting with Eve. […] ‘All the time, women were actually those who made decisions,’ Wiesel said, citing the importance of Ruth, Esther and Rahab in the Bible.”

Most of these biblical stories have been shown by modern archaeologists and biblical scholars to be fictional embellishments designed to hold the Jewish people together as a religious community. This lecture series is under the auspices of the Elie Wiesel Center for Judaic Studies at BU.

What is of greatest interest to us here at EWCTW is the final paragraphs of the article published in the Daily Free Press:

BU President Emeritus John Silber, who introduced Wiesel, emphasized the importance of Wiesel’s memoir, “Night,” which recounts his experience in the Nazi prison camps.

“In ‘Night’ [Wiesel] reveals the full horror of the Holocaust as an inscrutable evil,” Silber said. “‘Night’ has made millions of young students aware of this tragedy in which all standards of civilization were abandoned.” [see Wiesel’s description of Yael’s tactic of “hammering a peg through her enemy’s head” above -cy]

Silber said since Wiesel’s first lecture 34 years ago, the author has “made it his primary concern to arouse the consciousness of mankind to the realities of the Holocaust.”

Audience members said they were excited about seeing Wiesel at BU.

“I think that Elie Wiesel is a huge character and very, very inspirational to not just the Jewish people but also the whole world,” said College of Arts and Science [Jewish] freshman Ben Fishman.

“Elie is a faculty member who stands out, his name stands out on the paper when you see him on your schedule so when you have that opportunity it’s an opportunity you can’t pass up,” said School of Management freshman Albert Tawil. “That’s why BU takes pride in having him here.”

The second and third lectures in the series are scheduled for Nov. 1 and Nov. 8 at Metcalf Hall. Please see my blog on Opportunities for Activism here.

14 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: BU Dept. of Religion, Elie Wiesel Center for Judaic Studies, Hillel, Holocaust in Religion curriculum, Religion courses on Judaism vs. Christianity, Stephen T. Katz,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Tuesday, October 12th, 2010

Robert A. Brown, President of Boston University: “Elie Wiesel is a man of integrity and would not stoop to fabrication.”

With this statement, Dr. Brown replied to my September 23rd email message and postal letter to him, and to those copied, which I am publishing here.

Robert A. Brown

Office of the President

1 Silber Way, 8th Floor

Boston Ma 02215

September 23, 2010

Re: Prof. Elie Wiesel

Dear President Brown:

I recognize that Boston University has a long and admirable tradition of support for the humanities. One of your most prominent, most politically conspicuous faculty members is Elie Wiesel, who is associated in the public mind with a host of worthy, even noble causes, including being the recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize.

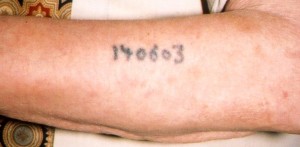

Particularly because of the honored position Professor Wiesel holds at BU, the questions that are being raised about his Holocaust testimony bother me, and I think if you were aware of them they would bother you, too. First is the lack of evidence that he has an Auschwitz tattoo, though he repeatedly claims to have one. As recently as last March, at Dayton University in Ohio, a student asked if he still has his concentration camp number, and he said, “I still have it on my arm.” However, his own 1996 video, in which his bare forearms are exposed to the camera, reveals no tattoo on his left arm, where it should be.

This, along with archival documents primarily from Buchenwald that show a Lazar Wiesel born in 1913, not 1928, who was there with his brother Abram, put his entire account of his concentration camp experiences of 1944-45 into question. No documentation for Shlomo Wiesel/Vizel, Elie’s father, or of a Lazar/Eliezer Wiesel with Elie Wiesel’s birth date of Sept. 30th, has been revealed.

Still other questions being raised concern his authorship of the original Yiddish version of Night. The brief description he gives of when, where and how he wrote And the World Remained Silent contain contradictions and improbabilities. In addition, there are major factual differences between key passages in Night, the English derivative of the original Yiddish language book, and Prof. Wiesel’s memoir All Rivers Run to the Sea. To mention just one—in the former, his foot is operated on before the evacuation to Buchenwald in January 1945, while in the latter it becomes his knee that is operated on! These are just a few of the red flags that are raised when studying Prof. Wiesel’s testimony with a critical eye.

I realize it is not my responsibility, but rather yours, to maintain the integrity of your faculty. However, I feel an obligation to bring this information to your attention because it is information that is gaining the attention of the world, and more importantly of your students, through various venues and investigations, and may reflect poorly on your great university.

Respectfully yours,

Carolyn Yeager

PO Box 439016

San Ysidro, CA 92143

Email: [email protected]

Web: http://www.eliewieseltattoo.com/

cc: David K. Campbell, Provost

Virginia Sapiro, Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences

Daniel Dahlstrom, Chair, Department of Humanities

Aaron Garrett, Assoc. Chair, Dept. of Humanities

Walter Hopp, Director, Undergraduate Studies, Dept. of Humanities

David Roochnik, Director, Graduate Studies, Dept. of Humanities

Members of the Board of Trustees

Robert A. Knox, Chairman

John P. Howe III, Vice Chairman

Jonathan R. Cole

Richard C. Godfrey

Robert J. Hildreth

Eric S. Lander

Alan M. Leventhal

J. Kenneth Menges, Jr.

Christine A. Poon

Adam. W. Sweeting

On September 27, I received a polite reply, which did not indicate whether Dr. Brown had looked at any of the pages I linked to on the Elie Wiesel Cons The World website.

Dear Ms. Yeager:

Thank you for your e-mail message of September 23, in which you express concerns about the accuracy of Dr. Wiesel’s testimony. I have no doubt that he is a survivor of the Holocaust and he has, thoughout his adult life, been a most eloquent witness to its atrocities. He is a man of integrity and would not stoop to fabrication.

Sincerely,

Robert A. Brown

We wanted to give the Boston University administration fair warning of what we are up to, and an opportunity to address the “Wiesel question” themselves.

Having done that, and after sending them a further reply suggesting that they look into the matter, and with no further response, we now turn to the students at BU. We have sent a message to student organizations, student publications and the local Boston media in a major effort to inform, encourage and assist students on campus to ask for answers to these questions. We believe there are individuals and organizations at BU who truly care about the ethical integrity of their university and its faculty, and who want to know the facts about all things, no matter how sensitive—not just accept what they are being taught by a timid, establishment faculty.

We suggest there is a simple request that Boston University students can make of Prof. Wiesel that their administrators are apparently unwilling to make. They can ask him to show his tattoo. He says he is a humble representative of the survivors of the concentration camps. Many Auschwitz survivors prove their presence in that camp by pointing to the number tattooed on their left forearm. Why not Elie Wiesel? Is he not one of them?

We’re urging students at BU, and all our readers as well, to write or call the following persons asking for their cooperation in a search for honest answers. Thank you for your activism.

Department of Philosophy

745 Commonwealth Avenue, Room 516

Boston, Massachusetts 02215

Phone:617.353.2571 | Fax:617.353.6805

Department e-mail:[email protected]

Department Chair: Professor Daniel Dahlstrom

Phone: 617.353.4583 | E-mail: [email protected]

Associate Chair: Professor Aaron Garrett

Phone: 617.358.3617 | E-mail: [email protected]

Director of Undergraduate Studies: Professor Walter Hopp

Phone: 617.358.4228 | E-mail: [email protected]

Director of Graduate Studies: Professor David Roochnik

Phone: 617.353.4579 | E-mail: [email protected]

Director of Graduate Admissions: Professor Allen Speight

Phone: 617.353.3067 | E-mail: [email protected]

Administrator: Matthew Roselli

Phone: 617.353.2572 | E-mail: [email protected]

Senior Program Coordinator: Lesley Moreau

Phone: 617.353.2571 | E-mail: [email protected]

Elie Wiesel: University Professor, Andrew W. Mellon Professor in the Humanities and Professor of Philosophy and Religion

E-mail: [email protected]

The full Dept. of Philosophy faculty addresses can be found on our Boston University Project page.

* * *

The Daily Free Press 648 Beacon St. Boston, MA 02215

Tel.: (617)236-4433 Fax.: (617)236-4414

The Daily Free Press welcomes comments and corrections from readers. To write a letter to the editor, send fewer than 500 words to [email protected] . Please include your phone number so that you can be contacted.

Neal J. Riley– Editor-in-Chief ([email protected])

Josh Cain – Managing Editor ([email protected])

Saba Hamedy – Campus Editor([email protected])

Chelsea Feinstein – Editorial Page Editor ([email protected])

WTBU Boston University’s student radio station broadcasting online.

General Manager – [email protected]

News Editor – [email protected]

Programming Editor – [email protected]

10 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: Boston University, BU Dept. of Philosophy, Robert A. Brown,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Wednesday, September 22nd, 2010

By Carolyn Yeager

copyright 2010 Carolyn Yeager

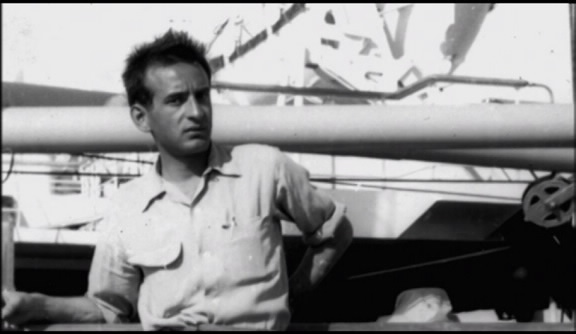

Elie Wiesel has been identified – in some cases has identified himself – in these three photographs. A close examination brings up many questions.

#1 – Elie in 1944, age 15 |

#2 – Elie on April 16, 1945, age 16½ |

#3 – Elie on April 27, 1945, age 16½ |

Do any two of these pictures look like the same person? You might think that picture #2 or 3 has a vague resemblance to picture #1, but pictures 2 and 3 don’t in the least resemble each other. The man in picture #2 has a sharp aquiline nose, high cheekbones, full lips and looks quite a bit older than 16 years of age, while the round-headed lad in picture #3 has a wide face, short nose and low forehead. He looks younger than 16.

Picture #2 can be recognized as a close-up from the Famous Buchenwald Liberation Photo. [see page under The Evidence]. Weasel has maintained since the 1980’s that this is his face.

Picture #3 is taken from the photograph below. He is the boy in front of the tall boy in the left column of boys leaving Buchenwald, fourth from the front (the third boy in line is hidden from view). He’s been identified as Elie Wiesel by Prof. Kenneth Waltzer on his Michigan State University website. Wiesel has not denied it. The U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, however, doesn’t claim that Elie is in this picture (see USHMM below).

Above: Children march out of Buchenwald to a nearby American field hospital where they will receive medical care. Buchenwald, Germany, April 27, 1945. — Wide World Photo [Photo and caption from USHMM website]

Below: From Ken Waltzer’s MSU Newsroom Special Report page

Elie Wiesel at Buchenwald

Elie Wiesel is fourth on the left, in front of the tall youth with beret.

Picture courtesy of the late Jack (Yakov) Werber, Great Neck, New York.

Waltzer writes on this same page:

In “Night,” Wiesel says that when he viewed himself in a mirror after liberation, he saw a corpse gazing back at him. But another picture [the one above] taken after liberation on April 17 [he has the date wrong], when the boys were led to the former SS barracks outside the camp, shows Wiesel marching out, fourth on the left, among a phalanx of youth moving together, heads held high, a group together guided by prisoners who had helped save them.

According to Waltzer, Elie Wiesel had a fast recovery to health, body mass and optimism, which Elie himself has never claimed. According to Buchenwald documents, these youths were not sent to France until July 16, 1945 (Fig. 12.4, 12.5),

Waltzer teaches German history and directs the Jewish Studies Program at MSU which includes courses on the Holocaust. He is writing a book about the orphan boys at Buchenwald titled “The Rescue of Children at Buchenwald.” Will Prof. Waltzer offer an explanation in his book for Elie Wiesel’s fit appearance in this photograph? He also accepts the man in the barracks photo as 16-year-old Wiesel. But then he has to, doesn’t he. How will he reconcile these two faces only eleven days apart?

USHMM

The USHMM features the picture shown below on its website—which Waltzer also refers to—and tells us that Elie Wiesel is among these boys without pointing out which one he is. Failing to find anyone who resembles Elie, I wrote to the USHMM asking them to identify him, but received no reply. [Update – because of a reader and also other pictures of Wiesel in France that surfaced later, I now believe Wiesel could be the darkish face in the 2nd to the last row, looking over the shoulder of the boy in a military-looking jacket and to the left of two boys in light-colored caps or berets. ]

Group portrait of Jewish displaced youth at the OSE (Oeuvre de Secours aux Enfants) home for Orthodox Jewish children in Ambloy. Elie Wiesel is among those pictured. Ambloy, France, 1945. — USHMM, courtesy of Willy Fogel

Group portrait of Jewish displaced youth at the OSE (Oeuvre de Secours aux Enfants) home for Orthodox Jewish children in Ambloy. Elie Wiesel is among those pictured. Ambloy, France, 1945. — USHMM, courtesy of Willy Fogel

The U.S. Holocaust Museum dates this picture simply as 1945. It is definitely summer; the boys are dressed in their suits and “traveling clothes,” as if they had just arrived. A large suitcase is being held by a young boy seated in the front row. It fits in every respect the records for the Buchenwald transport that left Germany for France on July 16, 1945.

Wiesel is careful not to give dates for many important events in his memoir All Rivers Run to the Sea. In this book he writes in detail about his trip to France and his early years with the Oeuvre de Secours. Yet he gives not a single date, until he mentions that he first met his future mentor, Shushani, sometime in 1947.1 He writes of being active with the other Jewish youths – engaged in classes, choir practice, trips and flirtations – but strangely not a single photograph is available.

The next picture of Elie Wiesel I have found was taken in 1949. In fact, it is the first picture of him we can be sure of since the 15-year-old portrait of 1944, prior to deportation (picture #1). Why are there no pictures of Wiesel during all the years he was in the Jewish welfare system in France? We are told his sister Hilda, living in Paris, recognized him in 1945 in a photograph of OSE orphans that was published in a newspaper or magazine. What picture was that? [This question was finally answered. See http://www.eliewieseltattoo.com/another-photo-of-young-elie-wiesel-that-is-not-elie-wiesel/ The group photo above? There are no easy or available answers to these questions. It doesn’t take much imagination, however, to consider that it’s because there aren’t any that “fit” the story.

I find it more than ironic that on the page “Elie Wiesel Timeline and World Events, 1928-1951” there are three photographs and Elie Wiesel is not in any one of them!

The next picture I can find of Elie Wiesel was taken in 1949, on a ship heading for Israel. We see here the real Elie – long, narrow face, long nose (but not aquiline as in picture #2 above), large ears, high broad forehead, a slender build. He is 20 years old and a journalist, and has probably never looked better. [Maybe that’s why the picture was released.] We learn in his memoir that on May 14, 1948, when David Ben Gurion read out the Israel Declaration of Independence, Elie Wiesel had been working already for around six months for the Irgun Yiddish weekly newspaper Zion in Kamf (Zion in Struggle)– yes, Irgun, the terrorist gang. He remained with the Irgun until they closed their European offices in January 1949. He was then persuaded to go where the action was—to Israel. Helped by the Jewish Agency, and traveling with a few Irgun veterans, he boarded the ship Negba in May or June (uncertain), crossing to Haifa, Israel.2 This picture must have been taken during that trip.

Elie Wiesel on a boat to Israel in 1949

Elie Wiesel on a boat to Israel in 1949

These are the faces of young Elie Wiesel during his “years of travail” that we have at our disposal—not much. I offer the opinion that too much is missing to accept unquestionably the story of his life, during these years 1944-1950, that has been manufactured for public consumption. Only two pictures: before Auschwitz and after his connection with the orphanage was concluded, are definitely him. The search continues.

Endnotes:

- Elie Wiesel, All Rivers Run to the Sea, Alfred Knopf, 1995, p 121.

- ibid, pg. 174-180

14 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: Buchenwald liberation, Irgun, Ken Waltzer, Oeuvre de Secours, Shushani/Chouchani, USHMM,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Saturday, September 11th, 2010

by Carolyn Yeager

copyright 2010 carolyn yeager

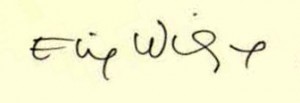

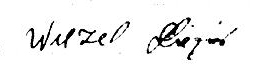

What can be simpler than to compare two signatures of the same name to determine whether they are indeed the same or two different individuals? Fortunately, we have available not only the signature of Elie Wiesel, but also that of Lázár Wiesel. The latter is on the “Military Government of Germany Concentration Camp Inmates Questionnaire.” This Questionnaire (Fragebogen in German) can be seen among The Documents pertaining to the Lazar Wiesel/Elie Wiesel question.

The importance of this lies in the fact that we only have one Lazar Wiesel at a time at Buchenwald, according to the records. Lazar Wiesel, born Sept. 4, 1913 arrived at the camp on January 26, 1945, along with his brother Abram, born Oct. 10, 1900, in a large transport from Auschwitz. They both have Buchenwald registration (or entry) numbers.

After the liberation in April, a questionnaire is filled out by a Lázár Wiesel who accents his name in the Hungarian style, giving a birth date of Oct. 4, 1928, and this Lazar is listed on the “childrens” transport to France in July. Neither of these Lazar Wiesel’s fit Elie Wiesel with his birth date of Sept. 30, 1928, and now I find his signature doesn’t match either.

On the left, Elie Wiesel’s well-known signature; on the right, the signature of Lázár Wiesel (last name is written first).

Two more examples of Elie’s book signing. The same style of open, very loose script is also found on the form he filled out for the Yad Vashem Central Database of Shoah Victims, testifying to his father Shlomo’s death at Buchenwald in January 1945. You can view it on their Internet site. Shlomo Vizel is on page 4 of the names.

Two more examples of Elie’s book signing. The same style of open, very loose script is also found on the form he filled out for the Yad Vashem Central Database of Shoah Victims, testifying to his father Shlomo’s death at Buchenwald in January 1945. You can view it on their Internet site. Shlomo Vizel is on page 4 of the names.

I suggest that this signature comparison leaves little doubt that the two men are not the same person. Elie Wiesel is NOT the Lázár Wiesel who was liberated from Buchenwald, or who traveled to France with the “Buchenwald Orphans.”1 The young Lázár Wiesel, born Oct. 4, 1928 according to these Buchenwald documents, and whose name and birth date appear on the transport list of “orphaned children” sent from Germany to France in July 1945 (see #14 on The Documents page) has such a visibly different style of writing from the Elie Wiesel who falsely claims to be on that list,2 that the two cannot be confused.

DATES OF ARREST DON’T MATCH

There is more evidence that they are not the same person in the form of the date of arrest shown on the same questionnaire. The date of arrest of Lázár Wiesel is given as April 16, 1944. That is the same day Samuel Jakobovits was arrested. Samuel and Lázár gave each others name as one of three references on their questionnaires, suggesting they were probably friends, or at least acquaintances, that had arrived at the same time.

Myklos Grüner’s date of arrest on his questionnaire is also 16 April 1944, from the city or surrounding area of Nyiregyhaza, Hungary. This can raise a question about the use of April 16 as some kind of “standard” date used by the military authorities in charge of the questionnaires. However, in his book Stolen Identity, Grüner does specify that on April 14, Hungarian gendarmes evacuated the entire population in the ghettos around the city of Nyiregyhaza, approximately 17,000 people. Six days later, “we too were driven from our homes” in Nyiregyhaza to a “holding area” leading to a railway track with a large loading platform, whereupon they boarded a “goods train.” Their destination was Auschwitz-Birkenau, where they would have arrived sometime between April 24 and April 30, 1944 (depending upon how long they stayed in the “holding area” before starting the 3 to 4-day journey).3

By contrast, we know by the authority of Elie Wiesel’s book Night that his family was not arrested on that date. In the “revised and updated” new translation of 2006, Wiesel gives his family’s date of deportation to the “small ghetto” as May 17, 1944. I arrive at this date because Wiesel writes that it was “some two weeks before Shavuot” (Shavuot fell on May 28 in 1944 4) that the deportation order was announced to his family and neighbors. [Remember, Sighet had 90,000 residents, at least one-third of them Jews, while Wiesel makes it sound like he lived in a little village.] Departures were to take place “street by street” starting the next day. That would be May 15. But the Wiesel family was scheduled to leave in the 3rd group, which left two days later, on May 17. After being marched to the “small ghetto,” they stayed there “a few days.” On a “Saturday,” they boarded trains.5 The 20th of May, 1944 was a Saturday

Thus, according to official concentration camp documents and Elie Wiesel’s own testimony, we can demonstrate that Lázár Wiesel was arrested approximately one full month prior to Elie Wiesel being arrested. Elie Wiesel is not the Lázár Wiesel of the Buchenwald documents.

Footnotes:

- Ken Waltzer will present on his book-in-progress, The Rescue of Children and Youth in Buchenwald, at James Madison College on April 11, 2007. In this book, Waltzer explores why, when the U.S. Third Army liberated Buchenwald, April 11, 1945, there were 904 children and youth still alive to be liberated. Among these were Elie Wiesel, a 16-year-old youth from Transylvania, (later Nobel Peace Prize winner) and also Israel Meir Lau, an 8-year-old child from Poland (later Israel Prize winner. http://www.jmc.msu.edu/faculty/show.asp?id=32

- It may be that Elie Wiesel has not made such claims himself, but they have been made by others to support the thesis that he is the one referred to. These others include Ken Waltzer, director of the Jewish Studies Program at Michigan State University, and the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.

- Nikolaus Grüner, Stolen Identity, Stockholm, 2005-2006, pg. 18-19

- “On the second day of Shavuot, 1944 (29 May 1944)” http://www.shtetlinks.jewishgen.org/Vamospercs/

- Elie Wiesel, Night, Hill & Wang, New York, 2006, pg.12-21.

14 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: Buchenwald liberation, Miklos Grüner, military govt. questionaires, Night, Wiesel signatures,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Sunday, September 5th, 2010

by Carolyn Yeager

copyright 2010 Carolyn Yeager

Part III: Nine reasons why Elie Wiesel cannot be the author of Un di Velt Hot Gesvign (And the World Remained Silent).

1. The only original source for the existence of an 862-page Yiddish manuscript is Elie Wiesel.