Archive for the ‘Featured’ Category

Tuesday, February 22nd, 2011

By Carolyn Yeager

copyright 2011 carolyn yeager

Edited for the 3rd time on March. 1st, 2011

1949-1955: Wiesel’s movements and life-support system during these years follow an odd pattern.

In January 1949, six months after the establishment of Israel as a state, the purpose for the Irgun presence in Europe changed. Their Paris newspaper Zion in Kamf no longer being necessary, the office shut down. “Elie Farshtei and his lieutenants, Joseph [Wiesel’s boss] among them, were recalled to Israel. I received no orders or aid from anyone. “Why don’t you come with us?” Joseph asked. I promised to think about it.” 11

This is problematic. Was Wiesel’s enthusiasm for Israel simply in his fantasy? The formation of Israel had seemed to mean everything to him; why would he not want to live there now it had become a reality? It was also a logical solution to his stateless status. Once again, we feel we’re not given the true picture. Was Wiesel “not recalled” with the others because he was more useful in Europe, where he could better serve the new state. He says he now returned to his “studies,” and “There were days when I was so absorbed in my reading that I never left my room. I had nothing to seek in the desert.” [Rivers, p 174]. The world around him in Paris, where he supposedly preferred to stay, he calls a “desert!” Actually Israel was a desert, not Paris. Wiesel reveals his disdain for the Gentile world, even though he takes advantage of everything it offers him.

After loafing about for awhile, his sister Hilda’s brother-in-law arranged to get him a press card, which gave him certain privileges. Wiesel worked it out with the Jewish Agency—which after Israel’s independence became the mandated organization in charge of immigration and absorption of Jews from the Diaspora—to travel to Israel. They prepared a plan for him to join a group of immigrants in May or June [1949], traveling from the train station in Lyons to Haifa. He had the idea to become a foreign correspondent for an Israeli paper.

The group happened to include a few Irgun veterans but they were leaving Europe for good, and I was ashamed to admit that I was less idealistic and above all less courageous than they. My wallet was not quite empty; a few thousand francs (my life savings) plus one pound sterling, a gift from Freddo. [P 175]

Here again, he attempts to show he is on his own, and poor, with the explanation that he can, but only barely, afford the trip. When they reach Marseilles and the sea, they go to a camp filled with Jews in transit, waiting for their passage on the ship Negba. Now he and the other Jews are in a transit camp where deprivations and close quarters are taken in stride. One man whom they asked about military service in Israel said:

Sure it’s tough, but consider this: Once I was a partisan, an underground fighter hiding in the woods like a hunted animal, not daring to come out except after dark, and now I’ll proudly wear the uniform of the Israeli army. [P 179-80]

This is a, perhaps unintended, confession of a Jewish “underground fighter” who “came out after dark” to attack the regular German troops. Wiesel comments on this, revealing his conspiratorial view of the world:

I grew up in a tradition that denies chance. Though not everything is predetermined, everything is linked. Nikos Kazantzakis (a Greek Jewish author) once said, citing an Etruscan proverb: “It is not because two clouds are joined that the spark ignites; two clouds are joined so that the spark may ignite.” Yet, free will and the possibility of choice exist. Rabbi Akiba tells us that all is foreseen, though human beings have free choice. [p180]

In other words, do events happen and result in a consequence, or is a desired consequence the cause of events happening?

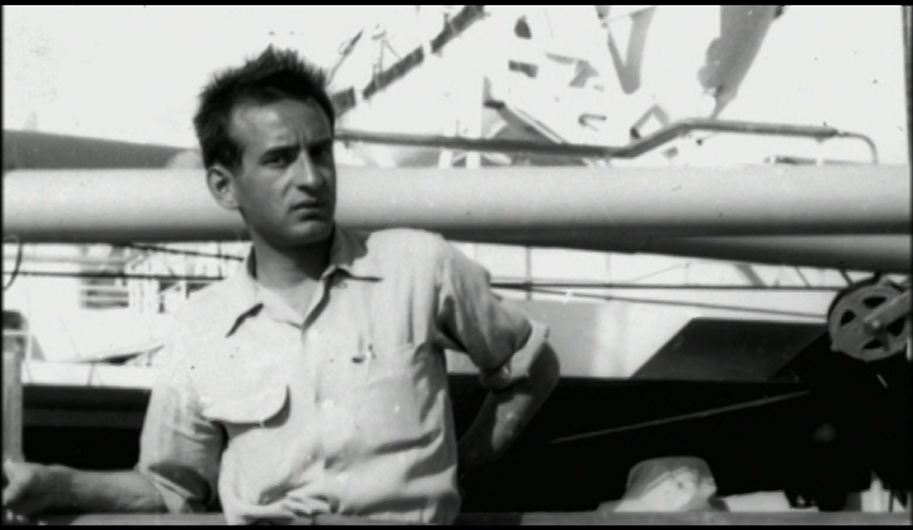

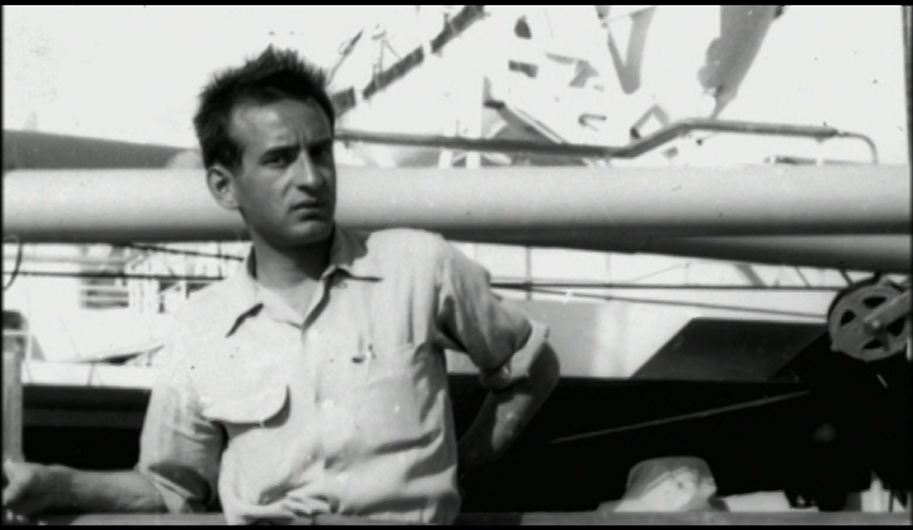

Elie Wiesel on the boat to Israel in 1949, at the age of 20.

In Israel, after his initial enthusiasm, and joy in walking on the holy ground, Wiesel was disappointed over the lack of acceptance among Jews. He heard complaints and recriminations … some people said they were “not accepted”—these were the camp survivors who were seen as weak by the new Israeli “natives.”

In this atmosphere little attention was paid to the Holocaust. For many years it was barely mentioned in textbooks and ignored in universities. In the early fifties, when David Ben-Gurion and his colleagues finally decided to pass the Knesset bill creating Yad Vashem, the Holocaust Memorial, the emphasis was on courage. Resistance fighters were presented as a kind of elite, while the victims—the dead and survivors alike—deserved at best compassion and pity. The subject was considered embarrassing. [p 184]

[It’s true the “Holocaust” was built up over time. Interest in it was fanned, beginning with the Adolf Eichmann show trial in 1961-62 and increasingly in the seventies, by the media and Hollywood. Elie Wiesel played a major role in establishing memorial museums, especially in Washington, DC , funded by U.S. taxpayers, playing on his theme of “Memory” with the help of influential newspapers with wide readership like the New York Times.]

Wiesel now says it was in Israel he got the idea to become a foreign correspondent. He writes that he got a recommendation to the editor of the small Yedioth Ahronoth newspaper, a Dr. Herzl Rosenblum, 12 a signatory of Israel’s Declaration of Independence as a representative of Jabotinsky’s Revisionist Zionist Irgun movement. Upon being hired by Rosenblum as the paper’s “foreign correspondent,” Wiesel sailed back to Paris on the Kedma, arriving in January 1950. [p 185]

I had lost track of Shushani 13 and François, but decided it would be a mistake to interrupt my studies on that account. I made a promise to myself. I vowed I would never spend less than an hour a day studying. [p 187]

Once again, it’s clear that, to Wiesel, “studying” meant reading on his own, not attending classes. Always needing to explain how he lived, he writes, “Money remained the problem. Once again, Shlomo Friedrich, my angel of mercy, managed to steer some free-lance translations and editorial work my way.” [p 188] We will see more of this type of explanation. Whenever Wiesel needs to solve the mystery of the appearance of needed cash, “free-lance” work is often the way he does it. Something to think about: Why Wiesel did not stay in Israel, among his own people who were so friendly and helpful, rather than choose to struggle in Paris as a stateless person? The most obvious answer is that he was assigned a job to do in France for the benefit of Israel. “I worked in my hotel room, a sunless cubicle overlooking the courtyard,” he writes.

In 1950, Elie Wiesel’s opportunities for travel begin … with a little help from friends

Suddenly wanting to return to Israel to talk to his new editor [or handler?] face to face, he somehow manages an appointment with a director of Zim Shipping.

I went to see a man called Loinger … a director of Zim, the Israeli shipping company. I explained … I had to go to Tel Aviv … Loinger understood immediately [!] … he picked up the phone and issued instructions …I was to be given a round-trip ticket on the Kedma that very day.[…] This crossing was very different from the last one. I had a comfortable cabin larger than my hotel room, a private shower, fruit and flowers on the table. [p 190]

This special treatment remains unexplained. Wiesel only tells us that, once in Israel, he visited with Dr. Rosenblum and became friends with his son, Dov. No discussion about his job is reported. Upon his return to Paris, “by chance” … by chance, mind you … he meets an official of the Jewish Agency who invites him on an automobile trip to Morocco. He “quickly” got an exit visa and a transit visa, “luckily” having enough photos on hand.

But what about money? I had one month’s rent on my room saved up. I took the money, stuffed everything I owned into an old valise, and that was that. There were three of us in the car. The first stop was Marseilles, where we stayed in the transit camp near Bandol. […] Now it was Moroccans who were waiting to “ascend” to Israel. [p193]

This is the same camp he was in before. Wiesel says he questioned the Moroccans, spoke to them in fluent Hebrew of how wonderful Israel was. This little speech was enough to bring him a large tip from the camp director.

The camp director was so pleased with my little speeches that he insisted on paying me ten thousand francs (two hundred dollars). At first I refused, but I finally said thank you and put the money in my pocket. We set out for the Spanish border, I was terrified of the police and customs officials who examined my stateless person’s travel permit. Would they take me for a Communist agent, a veteran of the International Brigades? True, I could tell them I was only eight to ten years old during their filthy civil war, but did fascists know how to count?

Ouch. What to say about this? First, $200 in 1950 was the equivalent of around $1000 today. Could a camp director hand out that kind of money to a stranger for relating some feel-good stories to his transient charges? Not unless he was rich and very generous. We can only believe this story as told if we understand the camp as part of the Jewish Agency network for assisting immigration into Israel, and the “director” as something more than just a camp director. More likely, he was quite aware of journalist Wiesel, and what his needs were. Secondly, Wiesel’s extreme bitterness toward the “fascist” Catholic-Franco Spanish state is apparent here. He knows he is not dealing with Jew-friendly power and is nervous without that support. But he had no trouble and the threesome made it into Morocco.

I was dazzled by the subterranean nightlife of Tangier, a cosmopolitan city of countless entrepreneurs, from the most honest to the shadiest. [p196 – Now this is a Jew-friendly place.] … We crossed Spanish Morocco at breakneck speed and, arriving in Casablanca, encountered a blinding but somehow soothing whiteness … My traveling companions had contacts within the Jewish community. [p 197]

I bet they did. A poorly dressed Jew offered to serve Wiesel as a guide; he proved to know his way around the Jewish community, introducing Wiesel to many and varied sorts of people . One Saturday afternoon they attended a meeting at a Zionist club. Wiesel writes that after “teaching a few songs” to the local members, his traveling companion from the Jewish Agency gave him an envelope containing money that seemed “princely to me,” assuring that there were “no more money worries for two or three weeks.” [p 198]

Wiesel says he wrote articles while there, without really understanding the culture. When he returned to France, he received a telegram from ‘Ifergan,’ his guide: “Your articles aroused anger. I am now in the hospital, with a few broken ribs.” Twenty years later, Wiesel wrote in Yedioth Aronoth about this “wrong” he had inadvertently caused, and received a response from ‘Ifergan’ that contained the following:

Don’t blame yourself. I was only doing my job when I followed you. I was working for the Mossad at the time, and they told me to keep an eye on you. The chance of having my ribs broken was part of the deal.” [p 199]

Why would the Mossad want to keep an eye on our young journalist? What other reason could there be than for his protection. Did the unnamed official from the Jewish Agency invite Wiesel to come along because of his gift for telling stories in impeccable Hebrew and teaching songs to emigrating Moroccan Jews? That seems too simplistic. In any case, Wiesel is definitely a precious commodity who is never left without funds.

Now … twenty pages later, though dates are not given, Wiesel reports feeling “disillusioned with Europe” and decides to travel to India. Prior to this, he was passionately involved with the negotiations on reparations with the Konrad Adenauer government. Heading for Bonn, Germany from France, he first spent a day at Dachau, where he says he was “troubled and depressed, for the Jewishness of the victims was barely mentioned.” [p 202] He is no doubt unaware to this day that few Jews were kept at the Dachau camp. Typical Wieselism!

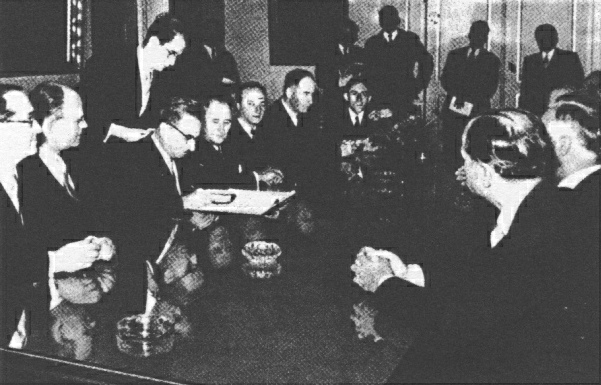

The Zionists offered him a well-paid job, with lodgings in a luxury hotel, as interpreter for Nahum Goldmann, the Polish founder and long-time head of the World Jewish Congress, at the conference of the WJC in Geneva. The Jews were deciding/debating the reparations issue among themselves. Wiesel says he was against the German reparation payments on the grounds they would lead to forgiveness or a “balancing of the shoah account.” Those in favor, such as Goldmann, argued the money for Israel was most important, while those against, including Wiesel’s former Irgun leader Menachem Begin, felt they stood on the moral high ground and would lose it by accepting financial compensation, which signaled “forgiveness.” Wiesel has always been against forgiveness. Goldmann has always been for the money, and “the Holocaust” was just another way to get it.

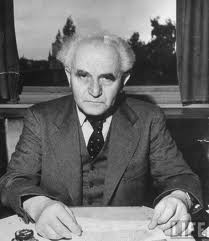

Left: Russian-born Nahum Goldmann, the long-time head of the World Jewish Congress, in 1966. Below: Moshe Sharett and Nahum Goldman, 3rd and 4th seated from left, signing the German-Israel Reparations Agreement in Sept. 1952

Miracles, miracles …Wiesel makes his most miraculous trip of all—a journey to India.

I had long dreamed of visiting India, drawn to it by a desire to meet not maharajahs but sages, yogis, and ascetics … why not compare the Jewish idea of redemption with the Hindu concept of nirvana?

Travel expenses were a problem. Yedioth had no money, so I didn’t even bother asking. I wrote ten articles for various Yiddish newspapers, promised ten more for later, did a few translations, and bought a lottery ticket for the first time in my life. Miracles of miracles, I won a modest amount, and at last I had a ticket in hand, but not much more. The two hundred dollars in my wallet would not take me far. [p 223]

Lottery ticket? Isn’t that the lazy Wiesel mind again, coming up with whatever explanation comes to him without bothering whether it’s believable or not? My interpretation is that he is so confident of being protected by varying sorts of ubiquitous “Mossad agents,” even those of a volunteer status, that he doesn’t need to worry. Or is he just having fun with us? At any rate, we have here the usual nonsense. He wrote “ten articles” [nice round figure] for “various” newspapers” and promised ten more [for a cash advance?]. I ask: If he could get this work whenever he needed it, why not do it all the time and end the relative poverty he claims he was living in? Also, note the $200 figure again. This is not the last time we’ll see it.

There remained the question of a visa. Dan Avni, press attaché of the Israeli embassy … phoned his Indian colleague and settled that matter for me.

What Indian colleague is he speaking of? India didn’t establish diplomatic relations with Israel until 1992. At any rate, there was an “Indian colleague” who arranged an entry visa for Wiesel. Do you think he also got some assistance while he was there? But he never mentions anything like this; he pretends he was just helped along by miracles. It’s pretty clear, however, that he had to have some kind of unofficial business to carry out for Israel. With diplomats easing his way, he was off.

During the crossing—with stopovers in Suez and Aden—I studied English, read […] A fellow passenger […] gave me the name of an inexpensive hotel in Bombay. [p 224]

The passenger was a “medical student” who also played the ponies. He convinced Wiesel to wager some of his $200. This doesn’t sound like something Wiesel would do, but he says he did and came out even. The passenger, however, lost his money and now convinced Wiesel to lend him his $200 [to bet more!] until they reached Bombay, where he would be able to pay Wiesel back. And Wiesel did so! When they disembarked at Bombay, a very worried Wiesel searched the crowd for his “friend” and, lo and behold, he showed up with the money in hand. This is a strange story. It sounds like the yarn of an inveterate story-teller, embellishing greatly on something that in reality was far less suspenseful. At any rate, it’s definitely not one of prudence; and may be told to demonstrate his uncanny “luck.”

Wiesel wanders around Bombay, encountering begging children and orphans. He “set out in search of the country,” but reveals no plan of any kind to his readers. How far would he get on $200/$1000? Well, naturally, a miracle intervenes.

One day I met a rich and influential Parsi. (Seemingly sitting at an outdoor café.) We chatted about this and that, and he found something about me intriguing. (His Irgun handshake?) […] Several hours later, as he left to return to his associates, he gave me a calling card on which he had written a few words. “India is a vast country, he said. “You will undoubtedly move around a lot. With this card you can take any domestic flight to any destination.” I didn’t know how to thank him. In fact, it took only a few weeks for me to appreciate the true value of his gift. Whenever I was hungry, I would get on a plane. By then I had discovered the identity of my benefactor: He owned the airline. [p 226]

How similar this is to his experience with the Zim Shipping Lines! Wiesel throws out these stories in his 1995 memoir with little concern for how flimsy they are. He is used to people believing him and not asking bothersome questions. Again, we’re not given the name of this “Parsi” or his airline – just as we find in the concentration camp stories by Wiesel, and by many others.

I ask: How practical is it to fly from one city to the next in order to eat a meal? You end up in another place. First you have to get to the airport, wait around for the flight, board and finally be served a meal. After that, de-board the plane, wait around for your return flight and another meal, land, de-board, leave the airport and return to your lodgings. By then you will be hungry again. Were airline meals worth it? This is India in the early 1950’s—a third world country. He says he did this for “a few weeks” at least. Wiesel says a lot of foolish things, and this is just one more. He obviously had sufficient money for this trip and probably free travel arrangements made by his handlers. He is lying outrageously to his readers.

We also learn very little of substance about the country and what he did. Back in Bombay, Wiesel spends a Shabbat with a wealthy Jewish family.

I went to synagogue. My hosts proudly told me of their success. The Sassoon and the Kadouris were super-rich families, veritable dynasties. But it had never occurred to anyone to discriminate against them because of their origins or their ties to Judaism. There were so many ethnic groups, languages, cultures, and traditions in this vast country that Jews did not attract special attention. […] I returned from India even more Jewish than before. [p 228-9]

There we have it—an explanation for the Jewish drive to racially and ethnically mix all nations but their own. It is so they will not attract special attention in the Diaspora with their super-wealth. Since Wiesel sees through eyes that can only admit Jewish persecution, he is often not aware of what he’s saying, and revealing, to the rest of us who see through very different eyes. This is a paragraph that should become better known.

There we have it—an explanation for the Jewish drive to racially and ethnically mix all nations but their own. It is so they will not attract special attention in the Diaspora with their super-wealth. Since Wiesel sees through eyes that can only admit Jewish persecution, he is often not aware of what he’s saying, and revealing, to the rest of us who see through very different eyes. This is a paragraph that should become better known.

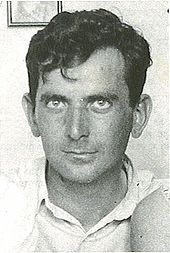

Left: Elie Wiesel in his early 20’s, at the time of these travels.

A few more trips—why not, they’re free.

A free ticket from El Al enabled me to visit Montreal. Bea [the younger of his two older sisters] seemed happy enough; she was now working at the Israeli consulate […] I desperately wanted to ask her a question that had haunted me for years. What was it like before the selection, those final moments, that last walk with Mother and Tsipouka? It was the same with Hilda. I didn’t dare. [p 229-230]

I’ve already commented on the reasons for this in Part II of this essay. Wiesel’s next trip is to Brazil, which I also discussed previously in “Shadowy Origins of Night” in relation to the writing of his ‘first book,’ the 862-page “lost” Yiddish manuscript. However, it is relevant to the Mossad question also.

It was Spring 1954. He was going on assignment for his newspaper Yedioth Ahronoth. It seems that some Jews who had recently arrived in Israel from Eastern Europe were poor and unhappy, and the Catholic Church, according to the Zionists, was taking advantage of their unhappiness to convert them to Catholicism with offers of free passage and visas to Brazil, and $200 each. [There’s that $200 for the third time! How to explain it? Wiesel is stuck on this number.]

His editor wants him to “go and see what’s going on” with this “Catholic scam” in Brazil. His poet friend Nicholas, an Israeli citizen, would go with him. But once again he needs to explain the money. As usual, “A resourceful Israeli friend somehow managed to come up with free boat tickets for us.” [p238] Oh, those Israelis are incredibly resourceful! Wiesel remained in Brazil for two months, but he doesn’t tell us what he did there besides writing about the Jew-Catholic “scandal” and visiting people, including relatives. When he was called back to Paris to cover Pierre Mendes-France’s accession to power for his Israeli newspaper, it was mid-June 1954.

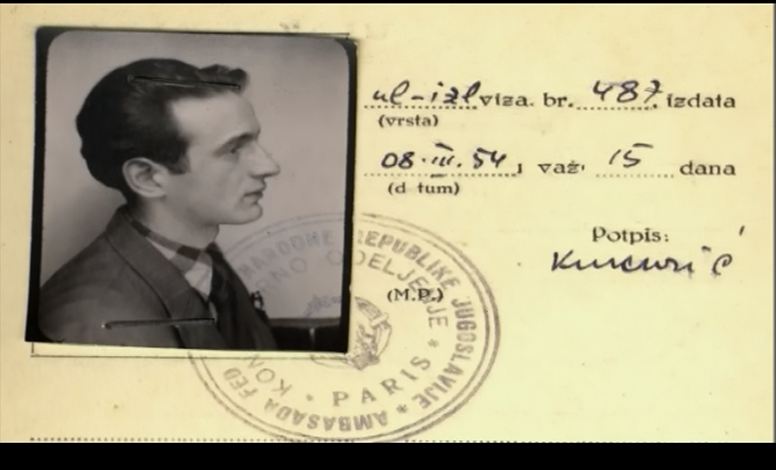

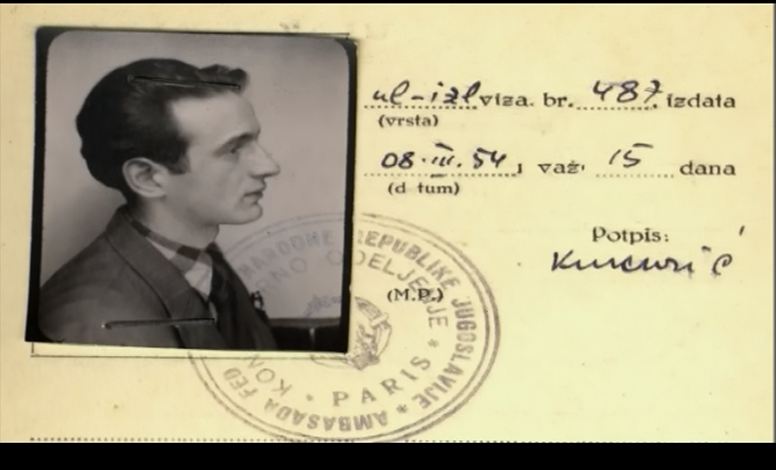

Document with Wiesel’s picture attached, dated (August?) 1954, issued by the Yugoslavian embassy in Paris . “Potpis” is Serbo-Croatian for “signature.” There is no mention of travel to Yugoslavia during this time, or any time, in Wiesel’s memoir. He appears thinner and more fragile-looking than in earlier photos when he was younger.

Document with Wiesel’s picture attached, dated (August?) 1954, issued by the Yugoslavian embassy in Paris . “Potpis” is Serbo-Croatian for “signature.” There is no mention of travel to Yugoslavia during this time, or any time, in Wiesel’s memoir. He appears thinner and more fragile-looking than in earlier photos when he was younger.

In July 1955, Wiesel makes another trip to Israel for the reason of “feeling once again the need for a change of scene.” [p 273] He went by sea and spent several weeks “making many trips through the country.” At Bnei Brak he visited the Rebbe of Wizhnitz, of his own Hasidic sect, to whom he made his famous statement that “certain things are true though they didn’t happen, while others are not, even if they did.” [p 275] That did not win him the Rebbe’s blessing.

At the end of his several-weeks stay in Israel, his editor Dov [the old man’s son] “proposed that I leave Paris and go to New York, not just to write a few articles, but as a permanent correspondent.” [p 276] Their conversation about this important decision is short and rather silly, same as with every other major event or life change that Wiesel writes about. We can easily conjecture that his Irgun/Mossad handlers thought there was now more value to be mined in New York than from his base in Paris. The German reparation talks were over, the amounts established; from now on, America was where the action was.

Next: Part IV – Déjà vu. Wiesel’s adventures in America follow the same, now-established pattern.

Endnotes:

11. Elie Wiesel, All Rivers Run to the Sea, A. Knopf, 1995, p174. [All following page numbers refer to this book]

12. Born in Kaunas in the Russian Empire (today in Lithuania), Rosenblum moved to Vienna after experiencing anti-Semitism and being prevented from studying law. In Vienna, he studied law and economics, gaining a PhD. He then moved to London, where he worked as an aide to Ze’ev Jabotinsky, a leader of the Revisionist Zionism movement. In 1935 he immigrated to Mandate Palestine and started working for the HaBoer newspaper, where he wrote under the pseudonym Herzl Vardi. In 1949, Rosenblum became editor of Yedioth Ahronoth. He remained as editor until 1986, during which time the paper became the largest selling in the country. His son, Moshe [called Dov], was later employed as editor.

13. In 1952 Chouchani left France for Israel where he remained until 1956, according to Wikipedia. See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monsieur_Chouchani

5 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: All Rivers Run to the Sea, Brazil, India, Morocco, Mossad, Nahum Goldmann, Yedioth Ahronoth,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Saturday, February 19th, 2011

Elie Wiesel asks: What came first—the event or the memory of the event?

When it comes to the Egyptian “revolution” or any other current topic he is asked about, Elie Wiesel reverts to the one idea animating his life: the power of memory.

When it comes to the Egyptian “revolution” or any other current topic he is asked about, Elie Wiesel reverts to the one idea animating his life: the power of memory.

“Bearing witness is a huge commitment; it has almost nothing to do with machines. It is the eye that sees, the ear that listens.” Thus he responded to someone calling from the International Herald Tribune for comments about Egypt

The 82-year-old said, “Because of technology, and because of the progress made in technology, especially in the field of communication, no one has any excuse anymore to say, ‘I don’t know; I didn’t know; I wasn’t aware.”

Speaking of the real-time availability of news today: “Since they come from a variety of sources, from a variety of people, representing all ideologies and all sensitivities, we know. We cannot not know,” Mr. Wiesel said. “Whether you want it or not,” he added a moment later, “we are witnesses.”

Wiesel fears that, “In one way, what worries me is that there is so much chatter that we forget how to listen. Everybody has something to say. Before speaking, there is thinking. But today everything goes so fast, so fast.”

What the chatter should be asking of Egypt, he said, is: “What does it mean? Why did this happen now? Why didn’t this happen before? And not who is wrong, because we have to listen to both sides. But the main thing is, What does it mean in history, to history?”

The Internet can serve as a repository of testimony; but it can also be a palace of fun house mirrors, in which events are reflected and twisted and spun even before they have ended.

“There is no life without memory,” Mr. Wiesel said. “But when it’s too much, when it’s too much, then we no longer know, really, what came first, the event or the memory of the event.”

* * * *

Finally, an interesting idea. Just how tricky can memory be? Can we remember something before it happens? Or that didn’t happen? Elie Wiesel seems to think so. And he should know, because he’s done it. Yes, the Master of Memory says: When it’s too much, too much, then we might find ourselves in a “fun house of memories,” twisting and spinning, and getting just plain confused. It can happen. ~cy

If you’re sure you want to, you can read the original article at http://www.nytimes.com/2011/02/12/world/middleeast/12iht-currents12.html

Thursday, February 3rd, 2011

by Carolyn Yeager

copyright 2011 carolyn yeager

The activities of the Irgun dominate Wiesel’s life and attention in 1948.

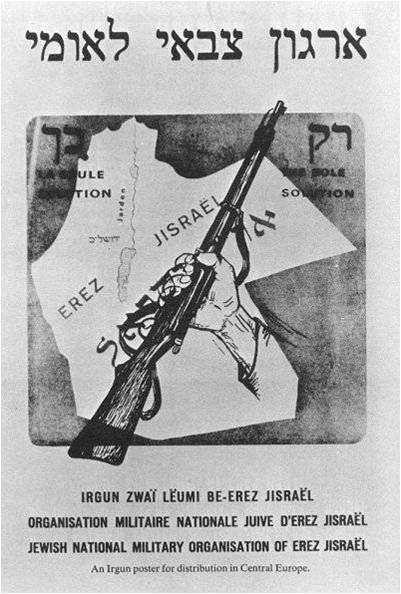

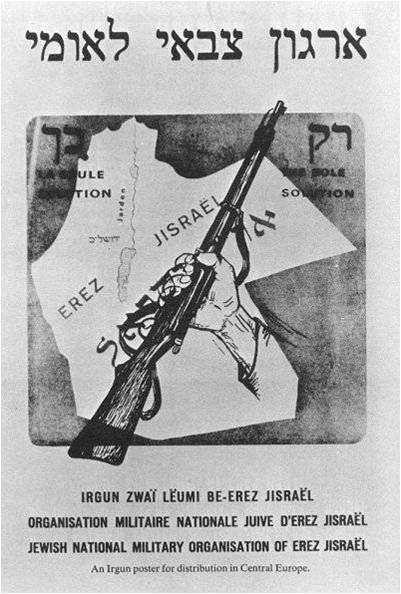

This propaganda poster, with the Hebrew words “This Way Only” on the artwork, was for distribution in central Europe. It was designed in 1937 by the wife of a Polish reserve officer who was working with Irgun representatives. [See story below: Irgun in Central/Eastern Europe] The entire area was called Eretz Israel and was claimed for a future Jewish state.

Dear Readers, As it has turned out, there is much to relate about this one year of 1948 before we get to Elie’s travels. Therefore, I ask for your patience once again. When we left off in Part I, he had just gone to work for the Irgun newspaper, Zion in Kamf. It was November 1947. Here is how he describes his vision of the underground “resistance” at this time.

Physical courage, self-sacrifice, and solidarity could be found even in the lower depths; total compassion, rejection of humiliation either suffered or imposed, and altruism in the absolute sense were found only among those who fought for an idea and an ideal that went beyond themselves. Nobility of action was found only among those who espoused the cause of the weak and oppressed, the prisoners of evil and misfortune. 5

Strangely, this sounds like the “ideas and ideals” of the National Socialists in Germany in the 1920’s who sought the way to lift themselves out of the humiliation and extreme economic hardship imposed on them by the Versailles dictate. But to young Wiesel, the only suffering worth seeing or talking about was that of the Jews. He had not a thought or concern about the native people in Palestine and what was happening to them, just as the Jews of the previous inter-war generation had no concern for the Germans they were exploiting. These others, for him, could not be seen as the “weak and oppressed,” but only as the new enemy that must be overcome by whatever methods were necessary. To Wiesel, even in his youth, only the Jewish militant fighters were “noble” when they carried out their tough and “necessary” actions.

Wiesel admits that by going to work for the Irgun in Paris he was: “risking neither death nor imprisonment. Even deportation from France was unlikely. Stateless persons were rarely deported, that was one of the few advantages of the status.” (Rivers, p162)

This again brings up the question of why Wiesel didn’t seek to become a French national. His sister Hilda had done so. Could it be that his underworld advisors were keeping open where he would be most useful? And as he himself said, being stateless had its advantages – useful for someone working on the fringes of illegality. Here’s how he describes his introduction to the Irgun.

The following Monday I presented myself at the editorial office. Joseph, the boss, showed me to a desk, handed me an article in Hebrew, and asked me to translate it. The article, published in the Irgun’s newspaper in Israel, was a denunciation of David Ben-Gurion and the Haganah and a paean to Menachem Begin, commander in chief of the Irgun. I translated the Hebrew words into Yiddish without grasping their meaning. I knew that the Haganah was fighting the British as hard as the Irgun was, and I couldn’t understand why the two movements hated each other so much. The article also mentioned the Lehi (the so-called Stern Gang), but what was its role? [p163]

I don’t think, after having two “best friends” working for the “resistance” [François and Kalman] and reading everything in the newspapers about the events in Palestine during the past year or two, that Wiesel is being entirely honest when expressing such naivete about the disputing militant factions. Continuing:

The article talked about a certain “season” during which atrocious acts were allegedly committed by the Jewish political establishment. I didn’t dare ask Joseph about this.

“I didn’t dare” brings to mind another passage he wrote on pages 229-30 describing a visit to his sister Bea in Canada. “I desperately wanted to ask her a question that had haunted me for years. What was it like before the selection, those final moments, that last walk with Mother and Tsipouka? It was the same with Hilda. I didn’t dare.”

May I suggest “I didn’t dare” is cover for the real reason—he doesn’t want an answer so that he will not know. And they – Bea, Hilda and Joseph – will be released from telling him something he will have to forget, or lie about. By not daring to know, he can remain blissfully naive about things that “happened, but weren’t real.” Or, were real but never happened?

Oddly, Wiesel’s mystic-mentor Shushani was also caught up in the Jewish assaults in Palestine:

Though he abhorred violence, he was hardly indifferent to the Jewish struggle in Palestine. Whenever the British arrested a member of an underground organization, Shushani tried to get information about his fate. One day he seemed extremely agitated. He interrupted our lesson, pacing, bumping into walls, blowing his nose, panting and wiping his forehead … It was the day a member of the Lehi and a member of the Irgun committed suicide together just a few hours before their scheduled execution. [p164]

I have had the suspicion that Shushani—the expert on the mysteries of life, the illumined one—also had connections to the Zionist intelligence network. Here we learn from Wiesel that he was so partial to the Jew’s fortunes in Palestine that he practically went into hyperventilation when two Jews met their death! Or is that just a typical rabbinic reaction, based on the belief that one Jewish life is worth a million Arabs. Think of the irony, though—that the British were executing Jews who were fighting against them in guerrilla uprisings, just as the Germans had done to Jews fighting as illegal guerrillas against their soldiers. I wonder if the wise Shushani could explain to me the difference?

Now, Wiesel wades in even deeper:

How and why did François suddenly decide to join the struggle for an independent Jewish state? Had he, too, knocked on the Jewish Agency’s door on the Avenue de Wagram? Though he joined the Lehi, and I belonged to the Irgun, our friendship was unaffected. In any case, each of us kept his activities to himself. We both agreed that the less we knew about each other, the better.6 No one asked questions at the synagogue I attended on the Rue Pave’e. To them I was a student like any other. If only they knew. [p165]

Wiesel is conscious of a separation between himself and ordinary people, even other Jews who would naturally be aware and following what was happening in Palestine with great interest and concern. He has gone much farther, and is actually working for those in the “lower depths” of the bloody struggle taking place. Another strange phrase is “I belonged to the Irgun.” In his signature manner, Wiesel covers up his true identity and objectives, but reveals them in the words that pop out unawares. I have commented about the psychological aspects of this trait among criminals elsewhere. So many luminaries of the “resistance” funneled through his office every day that he, by any measure, has to be considered something of an insider within the Irgun.

Above: Henry Bulawko, according to Wiesel one of his fellow camp survivors and an Irgun associate.

Haganah soldiers pose in 1948.

Through work I met Shlomo Friedrich, the leader of Betar, Jabotinsky’s Youth Movement. He was a tall, vigorous man with a rapid gait, a former prisoner in the Gulag.7 […] The process of becoming a journalist involved attending press conferences, public meetings, and demonstrations, and offered a chance to meet such “colleagues” as Henri Bulawko.8 As we talked, we discovered that we had been in Auschwitz-Buna at the same time. And I met Leon Leneman, one of the first to sound the alarm for Soviet Jews. […] Envoys from the Irgun came to the editorial offices every day. All were from Palestine and I was supposed to know only their aliases. Their commander, Elie Farshtei, was shrouded in mystery, but, after swearing me to secrecy, Joseph told me of an incident from his past. In 1946 … he was captured and tortured by agents of the Haganah […] I was flattered when Elie Farshtei stopped by to ask whether I wasn’t working too hard, whether my studies weren’t suffering. I told him that everything was fine, and that I hoped he was pleased with my “contribution” to “Zion in Struggle.” […] In the corridors I might have encountered a young Jewish girl from Vienna, beautiful and daring, who transported documents and provided a hiding place for guns: my future wife.9. [p166-7]

Elie was in deep admiration for all these and many other fighters. No “Nazi” could be more in thrall to the leaders of his movement. He tried to ingratiate himself and win their approval. There is never a hint of concern or questioning about the damage inflicted on non-Jews, of the “human rights” of the native Arab inhabitants. He mentions only Jewish casualties. “A wave of terror swept over the Jewish communities in various Arab countries.” A synagogue was burned, “dozens of Jews were slaughtered in Aden, Jerusalem was besieged” and “gangs loyal to the grand mufti, the pro-Hitler Haj Amin el-Husseini (former ally and protégé of Himmler), attacked Jewish villages and convoys.”

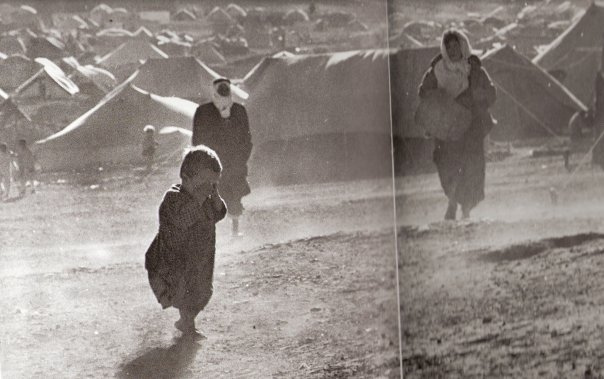

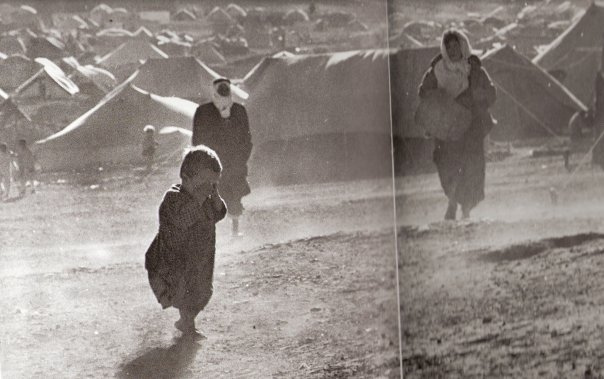

May 15, 1948: Beginning of a 62-year exile for 750,000 Palestinians

Tent city in Palestine, 1948

It would soon be May, and the day of independence. Mobilized units of the Haganah, the Palmach, the Irgun, and the Stern Gang united their efforts and their wills. It was imperative to protect every kibbutz, every settlement. The Zionist organizations in the Diaspora worked tirelessly to supply our brothers in Palestine with political and financial support. In France and in the United States as well, we were mobilized. Young and old, rich and not so rich, all felt the fever our ancestors had known in antiquity. Representatives of all the resistance groups worked day and night, though separately, procuring arms and ammunition, raising funds, recruiting volunteers who would set out for the various fronts of the nascent Jewish state. Elie [Farshtei] and his aides no longer found time to sleep. Out of solidarity, neither did we. [p167]

Excitement! All Jews, all over the world, were involved. Wiesel approved 100%, including the procuring of arms and ammunition. In spite of the fact that it was illegal, the “fever of our ancestors” justified it. You might be wondering why Wiesel didn’t speak in a more moderate tone when he wrote his memoir in the 1990’s; why he didn’t pretend a more universal concern for human rights in order to protect his reputation as a champion of human rights. I say he would not because he will never detract in any way from the utter righteousness of the installation of a Jewish state in Palestine. That can never be questioned, human rights be damned. That’s one reason Elie Wiesel is such a hypocrite. Other people’s struggles can be criticized and shown to be inimical to the rights of others, but never the Jew’s.

I find it interesting that Wiesel chooses the words “Young and old, rich and not so rich,” rather than “rich and poor.” There were no poor Jews? Or is it understood that this was a networking of those with means and influence; the poor were really of no help. They are just pawns in the game, used to parlay the idea that they are the ones for whom all this is being done.

My personal circle narrowed. Kalman left for America; Israel Adler was recalled by the Haganah and was now in a training camp …near Marseilles. My friend Nicholas informed me that he planned to abandon his studies [to go and fight.]

Deep down, I had reservations. Military life was not for me. […] what if I died in combat? I hadn’t yet done anything with my life, had written nothing of the visions and obsessions I bore within myself, hadn’t yet shared them with anyone. […] Nevertheless, I decided to heed the call to arms.

Nicholas and I signed up at the recruitment office … [p167-8]

Wiesel says he didn’t pass the medical examination. Really? Were they that particular? The doctor told him he was “not in good shape.” So he continued to work for the Irgun newspaper. Soon it was Friday, May 14, 1948, the day David Ben-Gurion read Israel’s Declaration of Independence over the radio. Wiesel claims to have been extremely moved, possibly beyond anything before in his life. “I was unable to contain my emotion. When had I last wept? It was in an almost painful state of reverence that I greeted Shabbat 10.” [p169]

Left: David Ben-Gurion reads the declaration of “Israel’s” independence, May 14, 1948 in Tel Aviv. A portrait of Theodor Herzl hangs above him. Right: Ben-Gurion, Israel’s first Prime Minister, in the same year.

* * *

The role of the Irgun in Central/Eastern Europe—collaboration with Poland, then Paris

At this point, I would like to insert some information about the role of the Irgun in Central and Eastern Europe from the website http://www.etzel.org.il/english/ac16.htm. It tells of the cooperation between the Polish government and Jewish “resistance” groups before the outbreak of WWII, revealing the desire of European nations, other than Germany, to reduce their Jewish population.

More than three million Jews, concentrated mainly in the large towns, lived in Poland in the 1930s. In Warsaw, for example, Jews constituted one-third of the population. The Polish government, worried by the increase in Jewish influence in the country, not only did nothing to hinder the illegal immigration movement which the Revisionists (Zionist faction of Jabotinsky – Irgun) organized in Poland, but actively assisted it.

In 1936, Jabotinsky met with the Foreign Minister, Josef Beck, and created the infrastructure for collaboration. The Polish government hoped that the establishment of a Jewish state would lead to mass emigration of Jews, thus solving the Jewish problem in Poland.

In 1937, Avraham Stern (Yair), then secretary of the Irgun General Headquarters, arrived in the Polish capital armed with a letter of recommendation from Jabotinsky. He met with senior government officials and laid the practical foundations for cooperation between the Polish army and the Irgun Zvai Le’umi. […] Polish army representatives handed over to Irgun members weapons and ammunition which […] were despatched to Eretz Israel. Some of the weapons were concealed in the false bottoms of crates in which the furniture of prospective immigrants was transported, or in the drums of electrical machines. When the consignments reached Eretz Israel, they were taken to a safe place, and the weapons were removed from their hiding place.

Stern was much helped by Dr. Henryk Strasman, a well known lawyer and an officer in the Polish Reserve force. The Strasmans introduced Stern to the Polish intellectuals and high officials. It was in their home that the preparations for the publication of the Polish periodical “Jerozolima Wyzwolona” (Free Jerusalem) were begun. His wife, Alicia (Lilka) designed the cover – A map of Eretz Israel with the background of an arm holding a gun and the words in Hebrew: ” ” (This Way Only). This became later the symbol of the Irgun. [See poster at top of page]

In March 1939, senior Irgun commanders from Eretz Israel participated in a course held in the Carpathian Mountains, instructed by Polish army officers. The course took place under conditions of great secrecy, and the instructors wore civilian clothing. The participants were not permitted to establish contact with local Jews, and the letters they wrote home were sent to Switzerland, inserted into new envelopes, re-addressed to France, and finally posted from there to Palestine. The trainees received military trainingand were taught tactics of guerilla warfare.

Three remained in Poland: Yaakov Meridor, who was responsible for despatching the weapons received from the Polish army; Shlomo Ben Shlomo, who organized a commanders course for selected members of Irgun cells in Poland, and Zvi Meltzer, who organized a similar course in Lithuania.

September 1, 1939 cut short the extensive activity of the Irgun in Poland and Lithuania. Most of the arms which the Irgun had received were returned to the Polish army and Irgun activity ceased.

After the war, the Irgun General Headquarters decided to renew activity in Europe and to launch a “second front”. The first base was established in Italy, […] As a result of arrests in Italy, Irgun Headquarters in Europe were transferred to Paris. Meanwhile, branches had been set up in various parts of Europe, and attempts were made to strike at British targets. A train transporting British troops was sabotaged, and an explosion occurred in the hotel in Vienna which housed the offices of the British occupation force. However, the blowing up of the British embassy in Rome remained the pinnacle of Irgun operational activity in Europe.

In January 1947, Eliyahu Lankin reached Paris after his successful escape from internment in Africa. Lankin was a member of the Irgun General Headquarters before his arrest and had also served as commander of the Jerusalem district. The French government, which knew of his escape from British custody, gave him an entry visa, and when he reached Paris he was appointed Commander of the Irgun in Europe.

Shmuel Ariel, sent to Paris by the Irgun in early 1946, was in charge of immigration. Ariel established good contacts with the French authorities, and the Haganah called on his services extensively in connection with sailings from France. Thus, for example, Ariel succeeded in negotiating with the French Ministry of Interior the granting of 3,000 entry visas to Jewish refugees arriving in France en route to Palestine. Some 650 of them left aboard the Ben Hecht, 940 on the arms vessel Altalena, and the remainder were transferred to a ship organized by the Haganah. Thanks to Ariel’s close contacts with the French authorities, the Irgun General Headquarters was permitted to operate in Paris without interruption, and to supervise activity in the many branches all over Europe.

While we hear so much about the “Transfer Agreement” and the Zionist collaboration with the German National Socialists under Adolf Hitler, where do we hear that beginning in 1936 the Polish Government was also desirous of, and actively engaged in, transferring their Jews to Palestine? As with the Germans, the breakout of war brought an end to this cooperation. But as soon as the war was over, it started up again in Paris. Paris was then the headquarters of the Irgun in Europe, with the approval of the French Interior Ministry. An Irgun special representative was in charge of illegal immigration to Palestine. Can this explain why Wiesel remained in Paris until 1955? It does shed light on the alternate world of underground Zionist operations that Elie Wiesel was absorbed into … just how deeply we can only speculate.

Next: Part III – Elie Wiesel’s travels and how they were funded.

Endnotes:

5. Wiesel, All Rivers Run to the Sea, p162

6. There is that “I didn’t dare ask” again; better not to know. You’re going to see as we go along that there are several phrases and numbers that Wiesel uses again and again.

7. In the Soviet Union, obviously.

8. A Lithuanian/Russian Jew born to an Orthodox rabbi, and a member of the French Resistance who was arrested in 1942

9. Wiesel is referring to Marion, whom he met and married later. As a “resistance” volunteer herself, she could well have delivered secret documents to his office.

10. Shabbat is the Jewish Sabbath, from sundown Friday to sundown Saturday.

7 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: All Rivers Run to the Sea, David Ben-Gurion, Elie Farshtei, Francois Wahl, Haganah, Henry Bulawko, Irgun, Shushani/Chouchani, sister Bea, Zion in Kamf,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Friday, January 21st, 2011

By Carolyn Yeager

copyright 2011 carolyn yeager

Updated on Jan. 24, 2011

What makes Jews special? Are they like “other people” or are they not? Here is one confusing answer from the world’s most famous holocaust survivor.

As I was compiling the particular sections in All Rivers Run to the Sea that reveal, in one way or another, Elie Wiesel’s sometimes certain, sometimes probable links to the Mossad and it’s precursors, I came across this interesting passage that shows something a little different—but equally important to the understanding of Wiesel’s views on crime.

Thus, I’m taking a short detour on the way to the promised “Elie Wiesel and the Mossad,” part two, but I will get there eventually.

On page 288 and 289 of Wiesel’s first memoir dealing with his life up to 1968 or thereabouts,1 he writes that, after his arrival in New York in 1956, his editor in Israel, Dov, suggested a report on organized crime in America. Wiesel tells us that when doing the research he discovered some Jewish names among the underground crime figures, even some working for the Irgun.

I’m sure that doesn’t surprise most of you reading this, and certainly not me, but Wiesel claims a different response:

These revelations came as a shock to me. I simply could not imagine a Jew becoming a hired killer. Yes, I had too idealistic a view of Jews, but the fact is that in Eastern Europe my people might have been criticized for just about anything, but not involvement in murders. Jews may have been guilty of lying or cheating, fraud or smuggling, theft or perjury, but murder was unimaginable.

Elie—who had worked for the Irgun for years in Paris; followed every fragment of news about the events in Palestine from at least 1946 on; was in communication with many of the behind-the-scenes characters responsible for the successful ascendance of the state of Israel—this man was shocked to learn that Jews were among the world’s killers, hired or not?

Left: Meyer Lansky, boss of the Jewish crime syndicate, was a Polish Jew born in Russia who emigrated to the U.S. in 1911; Center: Meyer “Mickey” Cohen, born in Brooklyn to Ukrainian Jewish parents, was a notorious mobster; Right: Moe Sedway, Lansky’s faithful lieutenant.

Wiesel is pretending to an idealism he had to have lost long ago, if he ever had it. When he says “I could not imagine a Jew becoming a hired killer,” the first thing that pops into my mind is Condoleezza Rice saying “We could not imagine an airplane being used as a weapon by smashing it into a skyscraper.”

Yet, he readily admits that Jews lie, cheat, commit fraud and acts of smuggling, theft and perjury (see Is Elie Wiesel a Perjurer?). I guess, in Wiesel’s mind, these crimes are not as bad as murder. But any one of them can result in death to the parties victimized by such crimes, and anyone committing them has to know the harm they are doing to these others. We also know that lying and cheating are commonly done by Jews against non-Jews, and that the Talmud and the Torah not only excuse these crimes but in some cases recommend them! Fraud, smuggling and perjury necessarily combine both lying and cheating.

In a way, Wiesel, as a religious Jew well-versed in the scriptures, seems to be excusing these practices because they are less than murder, the one crime Jews should never do. But yet killing for the attainment of Eretz Yisrael, as did all the “resistance fighters” he so admired, must be acceptable to his Zionist eyes.

Let’s see if there’s an answer in his following paragraph:

I like to think that what accounts for this virtual absence of blood crimes in our communities was perhaps related to the commandment revealed at Sinai: Thou shalt not kill. The voice of God sounds and resounds in our collective memory. But then what accounts for the present reality? The fact is that in modern Israel acts of murder do occur. True, there are few such cases, but even one is too many. It seems we are finally becoming a people like any other, neither better nor worse. Does this mean we are not “the chosen people?” No, we are, but only in the sense that Anglo-Jewish writer Israel Zangwill attributes to the term: “the people that chooses itself, its destiny and mission.” And as important, in the sense of teaching all peoples that they, too, must aspire to reach beyond themselves, to lift themselves ever higher, and to see themselves as unique.

Wiesel tells us that Jews became murderers when they became more like the rest of us. Does history bear that out? Can it not be demonstrated that what accounts for the absence of blood crimes within Jewish communities is related to the commandment not to do harm to your fellow Jews—but the same does not apply to non-Jews. The Ten Commandments were applied to fellow Hebrews, not to outsiders. This is more likely what accounts for the present reality. Jews in the Diaspora have plenty of targets which are not forbidden to them to harm.

But Wiesel is complaining that murders now occur among Jews in modern Israel. [And we are again served up that obligatory cliché: “Even one is too many.”] He explains this downward drift by saying “we are finally becoming more like other people.” But to assure they remain “the chosen,” he is willing to make quite a concession—that it is not God who chose that Abramic tribe centuries ago, but they have chosen themselves.

Goyim have been saying that for a long time, but little did we know that Elie Wiesel would one day agree! But does he really, or did he talk himself into a corner, then try to talk himself out of it? He concludes that the Jewish mission is to “teach all peoples that they, too, must aspire beyond themselves; they, too, should lift themselves higher; they, too, should see themselves as unique. I had not thought we were trailing so far behind those darn Jews. Is it because Jews do not murder their own for hire? That may be true. But I will venture to say that Jews are routinely implicated in causing non-Jews to attack and murder each other. That cannot be OK. And there is the ironic “fact,” as Wiesel says elsewhere in his memoir, that it was Cain who slew his brother Abel at the beginning of the Jewish story.

Chabad-Lubavitch members visit the White House regularly bearing sentimental mementos, such as menorahs, to make sure their interests are not forgotten. The Chabad originated in Russia and are of the same Hasidic sect as Elie Wiesel. Is it their uniqueness that Wiesel thinks the Goyim should aspire to?

Elie Wiesel goes to Las Vegas in 1957

On pages 301-2, I found another interesting passage that adds to the above. After his first year in New York, Wiesel’s editor Dov, with his wife Leah, came from Israel for a long visit. Dov was fascinated with all things American. Wiesel took them to concerts and restaurants in New York; then Dov rented a car for a six-week cross country trip for the three of them. One place they stopped was Las Vegas, which, after the war, was built up mainly by Jewish crime figures.

In 1946, Jewish gangster “Bugsy” Siegel, with help from friend and fellow mob boss Meyer Lansky, used dirty money laundered through Mormon-owned banks to build The Flamingo gambling casino. Siegel experienced financial difficulties and died in a hail of gunfire in Los Angeles, CA. Other mobsters saw the potential that gambling offered in Las Vegas. From 1952 to 1957, still using some Mormon bankers and adding Teamsters Union funds, they built the Sahara, the Sands, the New Frontier, the Royal Nevada, the Showboat, The Riviera, The Fremont, Binion’s Horseshoe, and finally The Tropicana. Already in 1954 over 8 million people were visiting Las Vegas yearly, pumping 200 million dollars into casinos. By 1957, when Wiesel arrived, it was the heyday of the flashy, openly-mobster-run Vegas. 2

Wiesel found comrades with strong Israeli ties there, as he does everywhere. He writes sparingly about it:

There was Las Vegas and its slot machines, available even in the rest rooms. Men and women were standing in dazzlingly bright casinos, betting a year’s salary or more on a little ball that leaps and dances about indifferently, stupidly, before coming to rest on a number , any number. Wherever you turn, you see frozen faces and trembling hands. The casino in Monte Carlo 3 is the playground of the rich, who seem burdened by their wealth. In Las Vegas one sees ordinary people fed up with not being rich.

At the Sands Hotel we dined with Hank Greenspun, a powerful man in the city who was the owner of the daily Las Vegas Sun, who told us of his clandestine activities in support of Israel. In 1948 he was involved in an illegal arms shipment, for which he was indicted and sentenced to several year in prison. Of this he was very proud.

Well known Las Vegas Jewish crime figures. Left: Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel; Right: Israel “Icepick Willie” Alderman, Joe Rosenberg, Gus Greenbaum

Below: Frank Sinatra, Hank Greenspun and Eddie Moss, bookie and casino manager of the Sahara Hotel.

Greenspun may have been sentenced to prison, as Wiesel says, but he didn’t serve any time. According to Wikipedia, in 1947 he was shipping guns and airplane parts to the Haganah fighters in Israel. He was arrested and convicted of violating the Neutrality Acts. Fined a relatively small sum of $10,000, he received no prison time. In 1961, President John F. Kennedy pardoned Greenspun, and when he died in 1989, former Israeli PM Shimon Peres called him “a hero of our country and a fighter for freedom.” Greenspun purchased the Las Vegas Sun newspaper in 1949, which he ran until his death. 4

Wiesel doesn’t tell us how he and his editor managed to link up with Hank Greenspun, but then it goes without saying. By 1957, Greenspun was able to entertain and regale visiting Jews and Israelis of note with his illegal exploits for terrorists operating in Palestine. A few years later, his crime was washed away by a U.S. president.

Endnotes:

1. Elie Wiesel, Memoirs: All Rivers Run to the Sea, Alfred A. Knopf, 1995. 418 pp.

2. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Las_Vegas

3. He means the one in Monaco, on the French coast.

4. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hank_Greenspun

7 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: All Rivers Run to the Sea, Hank Greenspun, Irgun, Jewish crime, Las Vegas, Meyer Lansky,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Friday, January 14th, 2011

Hailey S. from haileylovespink@… has written to us and we think it’s such a great letter that we’ve inaugurated a “Letter of the Week” blog just for it. We might not get a good letter like this every week, or even every month … but when we do, we’ll share it with you. And we assure you, we haven’t changed a word or a letter, or corrected any spelling. This is exactly as we received it.

Hailey writes:

I think you have some serious issues, if this is what you are dedicating your life too. This man has a message, and has been changing lies. You can’t argue with the evidence. Just because you have some stupid false testimonies doesn’t mean they’re true. This is the biggest waste of time I have ever seen, life goes on. & the past stays the same. You can’t change it. So why don’t you dedicate your life to something more important, like getting off of your computer. K, BYE.

Well Hailey, I’m not dedicating my life only to this, but right now it’s pretty important to me, I admit. You got me there.

I am glad you recognize that “this man” has been changing lies. You are way ahead of most in that recognition. Even though changing lies is one of the really strong habits of this man, most people refuse to notice it. You’re right, too, that no one can argue with the evidence for that—there’s just too much of it. And who can argue against your comment that stupid false testimonies are not necessarily true—especially if they’re false! Wow, you’ve nailed it.

If this is true, you shouldn’t think what I’m doing here is a waste of time. You are right, though, that life goes on. It does. Yet you say the past doesn’t go on, it stays behind and doesn’t change. Hmmm. That seems to mean that changing lies doesn’t work because you can’t change the past no matter how many lies you change. Now, that seems to me to be a reason to keep dedicating my life to this, and to stay on my computer. Can you see the logic? I hope so.

Hailey, I loved your letter and really hope you will write again. Even though you don’t like stupid false testimonies, keep reading this website (which unfortunately is full of stupid false testimonies) and let us know what you think. Bye now …Carolyn

Monday, January 10th, 2011

Has conformism completely overtaken free, questioning, adversarial minds on today’s university campuses?

February 1st is the deadline for us to receive essays in our “A Question of Ethics” Essay Contest, for which we have $1000.00 set aside for prizes. That is just 21 days from the date of this posting, yet we have not, as of this date, received even one.

Can it be that $500.00, $250.00 and $125.00 doesn’t tempt even a few students out of the thousands at Boston and Chapman Universities, where we have advertised our contest? According to the odds, we could expect at least a handful who would be independent enough, and smart enough to figure out that the fewer the entries, the greater the chance of winning. After all, the prize essays would not necessarily have to be of doctoral dissertation quality! They would only have to follow the evidence presented on this website, use proper grammar and punctuation, and be posted here with the winner’s name. Ay, there’s the rub.

Your name and your essay will be posted on this site. What sort of retaliation by teachers, administrators, and your fellow students would you have to endure? And would the stigma follow you for the rest of your life? Might you possibly have difficulty, as someone identified as flirting with “holocaust denial”, with that post-graduation trip to Europe that you’re hoping to make? The idea of such repercussions makes even the $500 of little value, and the intellectual challenge that may have lit a small fire in your mind is easily damped down and put out. Why chance it? The drawbacks outweigh the benefits.

Yes, we understand. We offered this essay contest for straightforward reasons, but we also knew it would be a good lesson in how the weight of political correctness on our college campuses, particularly around this issue and even more particularly around the person of Elie Wiesel, is strangling freedom of thought, freedom of intellectual pursuit in areas of politically-enforced belief structures, and freedom to express your “different” views openly.

Our contest will either bear fruit in the form of essays to read, judge and discuss, or it will bear fruit as an example of the suffocating, silencing effect of the politically-enforced “new religion” of our time—the sacred, unquestioned memory of “holocaust survivors.” But bear fruit it surely will. It is up to you, students of Boston University and Chapman University in Orange CA, which it will be.

Herewith, for the last time, is our original announcement:

“A Question of Ethics” Essay Contest announced for Boston and Chapman University students; $1000 in prizes

We are pleased to announce the first East Coast—West Coast “A Question of Ethics” Essay Contest for students enrolled at Boston University in Massachusetts and Chapman University in Orange, California.

The winning essay will be awarded $500; second prize will receive $250; two honorable mentions $125 each. The winning essays will be published on the web site Elie Wiesel Cons The World.

The essays must analyze one or more ethical issues surrounding Elie Wiesel as they are presented on the pages of the website Elie Wiesel Cons The World. These issues may include [not in order of importance]

- Prof. Wiesel’s refusal to show his claimed tattoo.

- The documents from Buchenwald that do not support Wiesel’s presence there.

- His claim to be in the famous Buchenwald Liberation Photo when, according to his book, he was deathly ill in the hospital at the time.

- His close association with the Irgun terrorist gang in the late 1940’s.

- The questions surrounding the authorship of his first book, Un di Velt Hot Gesvign, allegedly 866 pages written in less than two weeks while on a ship crossing the Atlantic.

- The insistence that his book Night, read by school children all over the world, is a factual account of his experience at Auschwitz and Buchenwald.

Though the essays must utilize the information made available on Elie Wiesel Cons The World, information from other sources is acceptable as additional material. Our objective is for the essayists to examine the ethics challenges facing Prof. Wiesel in light of the information we have provided at our website.

Deadline for essays to be received is Feb. 1st, 2011. To be considered for a prize, essays must be a minimum of 500 words. Proof of registration as a student at Boston or Chapman University must accompany the essay. This can be a copy of one’s current semester course registration along with a University ID card. Manuscripts should be emailed to [email protected] with the subject line: Ethics Essay Contest.

Contact:

Carolyn Yeager

c/oCODOH, PO Box 439016

San Ysidro, CA 92143

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.eliewieseltattoo.com

No Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: Boston University, Chapman University, essay contest,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Sunday, January 2nd, 2011

By Carolyn Yeager

copyright 2011 carolyn yeager

Is Elie Wiesel just another Mossad asset? The question is not as surprising as it may sound.

The question of how involved Elie Wiesel was with the early terrorist groups that eventually became The Mossad, Israel’s feared intelligence arm, is one that must finally be asked and answered in a straightforward manner. Certainly, Wiesel is no stranger to politics from his young years. Zionism, along with Marxism and Communism, had strong currency among Eastern European Jews during the 20’s and 30’s; it grew only stronger in the atmosphere of the concentration camps and ghettos created by the Hitler regime and its allies during WWII.

By the time the camps were “liberated” and their inmates, along with others who desired to move about and get a new lease on life, streamed into the Allied Displaced Persons [DP] camps in Germany in 1945, the Zionist cause had reached fever-pitch. These camps, in which all Jewish people were treated with most-deserving status—no matter how they behaved or what their actual past had been—were hotbeds of recruitment for Jewish “resistance” groups such as Haganah, Irgun and Lehi, as well as for illegal transportation and entry into Palestine.

Background of Jewish Terrorist Organizations

The first Jewish paramilitary organization, Haganah [“The Defense”], was formed in 1920. It guarded the Jewish settlements that were forming in Palestine from the Arabs, who were beginning to resent the intruders. In 1931, the more militant elements of the Haganah splintered off and formed the Irgun [also called Etzel and “Defense B”], led from 1943-48 by Menachem Begin.

After 1945, the Haganah was a full-fledged terrorist organization, carrying out bombings, sabotage and illegal immigration of Jews into Palestine. Famous members included Rabin, Sharon, Dayan, Zeevi and Dr. Ruth Westheimer. After Israel became a state in 1948, the Haganah became the Israeli Defense Force.

The Irgun policy was based on ultra-radical Ze’ev Jabotinsky’s “Revisionist Zionism,” which declared that every Jew had the right to enter Palestine, and that active retaliation and Jewish armed force were necessary methods to ensure the Jewish state. It was the Irgun that bombed the King David Hotel—killing 91 people and injuring 46—and carried out the infamous Deir Yassin massacre, along with the Lehi [the Stern Gang]. The Irgun is the predecessor to today’s Likud Party.

![EW_Stern [gang]](https://www.eliewieseltattoo.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/EW_Stern-gang1.jpg)

(L)Avraham Tehomi, the first Commander of the Irgun; (C) Ze’ev Jabotinsky, Irgun ideologist; (R) Avraham (Yair) Stern, founder of The Stern Gang

A commander in the Irgun, Avraham Stern, defected from the Irgun and founded the Lehi group, also known as the Stern Gang, They were even more fanatical than Irgun, and declared total war against imperialism and the British Empire, even while the British were at war with the Germans.

After May 14, 1948 [Israel’s independence], Irgun representatives in France purchased a ship and weapons, and brought it to the Israeli coast in violation of a ceasefire agreement with the neighboring Arab states and the United Nations. It was with the Irgun in Paris, France that Elie Wiesel found his first job.

Wiesel in France

Wiesel writes in All Rivers Run to the Sea 1, his memoir, that he and his young fellow “survivors” wanted to go to Palestine right from Buchenwald, but their American liberators couldn’t allow them to do that. They settled for free transportation and lodgings in France, sponsored by a Jewish welfare agency, the OSE, and the government of Charles De Gaulle.

Now, if it turns out to be true that Wiesel was not at Buchenwald, as I believe, then he was not on that particular passenger train trip to France that he describes on page 109 of his memoir All Rivers. There, he gives a strange explanation for why he never received French nationality:

The train stopped at the border, and they had us get off. A police official made a speech, of which I understood not a word. When I saw people raising their hands, I assumed they were volunteering for some task. […] I later found out that the policeman had asked for a show of hands of all those who wished to become French citizens. Since I did not respond, they probably wrote in my file: “Refused French nationality.” The consequence of my blunder was endless harassment and administrative hassles …

This is questionable for several reasons. First, he says prior to the above paragraph that he shared a train compartment with a boy from Sighet who knew a few words in French. But why would any of the boys be expected to know French? They wouldn’t. Second, there were two Jewish American Army Chaplains accompanying them who were supposedly looking out for their welfare. Third, Wiesel says, “They probably wrote in my file.” Didn’t he ask about it? Certainly he would have gotten another chance once he explained his mistake to the welfare authorities, since the point of the whole operation is that the boys from Buchenwald, if they were orphans, were offered to become French Nationals.

This simplistic and nonsensical explanation for why he spent years as a “stateless person” is just not convincing. It does not fit the world as we know it. This will be repeated in following explanations he gives for his experiences.

Wiesel writes that they were greeted by the OSE, the children’s rescue society, with all good things: a splendid chateau, lavish meals, smiles and promises. His smaller “group of young believers” requested kosher food and received it. They were also provided with their requested bibles, prayer books and Talmudic tractates, and a study/prayer room.2 Wiesel appears not to be interested in assimilating as a Frenchman, even though he finds his eldest sister to be living nearby. Among this group of youths were Zionists and Bundists. Elie was the former, while the Bundists preferred to “rebuild a Jewish cultural life in the Diaspora.”

Wiesel says he “rededicated” himself to his sacred studies, and in between played chess. One day:

…a couple of strangers wanted to take pictures as we played. One of them asked some questions in bad German; I answered in good Yiddish. Someone said they were journalists, but I had never met a journalist before; they were of no interest to me, and I didn’t see why I should interest them.3

This became the published photograph that is said to have alerted his sister Hilda, who had married an Algerian Jew and was living in Paris, to his whereabouts. In a few days, she had contacted the OSE and the brother-sister reuniting was arranged. But why have we never seen this picture? Why has it disappeared and why does no one of the holocaust historians or Wiesel biographers care enough to search for it? We can reasonably expect that sister Hilda would have kept that magazine picture as a treasured memento, but once again we are confronted with the unexplainable. 4

It was many months later that he reunited with his second sister, Bea, who was in a DP camp in Germany, waiting on a visa to the U.S. or Canada. According to All Rivers, Bea had traveled to Sighet, where Elie had refused to return. There, someone she met told her that her brother was alive. No further details on this—how and why she went to Sighet, and why the folks there would know. At this point in the memoir, Wiesel writes some very sentimental passages that take our attention away from his sisters’ discovery of his whereabouts, and never gets back to it.5

Early connections with Jewish Resistance

The next item of interest to our topic comes on page 120 of All Rivers. In 1947 the OSE arranges for a young Jewish teacher, François Wahl 6, to give Wiesel private French lessons, since he has decided to remain in France for the time being, rather than to emigrate to Palestine [illegally] or to the Americas or Australia. Wiesel writes that, while only two years his senior, Wahl seemed much older, and that “the bond between them was deep and true.” He then informs us that “in 1947, as the underground war raged in Palestine, François performed important secret tasks for a Jewish resistance group.”

During this time, Wiesel’s stated pursuits had solely to do with Jewish religion and politics. Actually, that has never changed, in spite of the effort to make it appear that he was, for a time, a real student at the Sorbonne [see here]. He associated only with other Jews, all of whom were naturally interested in the events in Palestine, by staying within the Jewish welfare system even though he was transferred twice—first to Taverny, then to Versailles. At the latter, he was not only with his Buchenwald group but with other Jewish orphans who had given themselves false identities and/or had lived with Christian families during the war.7

When Wiesel’s best friend Kalman left for Palestine [illegally], Wiesel stayed behind and kept up his love affair with Jerusalem from afar. There can be no doubt that he was familiar and highly sympathetic with the Zionist ideas of forcing their way into Palestine, and had no qualms about their methods.

On page 150 he confides: “I had wanted to write ever since childhood. In Sighet I often went to the offices of the Jewish community to write a page of Bible commentary on the only available Hebrew typewriter.” [See my questions about Wiesel’s typing ability here.] On the same page, Wiesel questions the value of writing, and more particularly, of words themselves.

… I told myself I should write. But I had to be patient. Someday, in years to come, I would celebrate memory, but not yet. Even then I was aware of the deficiencies and inadequacies of language. Words frightened me. What exactly did it mean to speak? Was it a divine or diabolical act? The spoken word and the written word do not reflect the same experience. The mysticism with which my adolescence was imbued made me suspicious of writing.

And on and on. This is a person caught in such a narrow perspective of life based on readings of Judaic mysticism that he has difficulty seeing anything just for what it is. Also, someone who forever contradicts himself. He wants to write but is frightened of words; he loves and hates at the same time.

At the “end of summer” the counselor finally persuades Elie to leave the comfort of Versailles and take a room of his own near the counselor’s home—he was nineteen and one of the last of his group to leave. From here, he continued seeing his mentor Shushani, his French teacher François, and followed Jewish current events closely. He says he bought the newspapers regardless of the expense.

Finally, the momentous event of the U.N. resolution of Nov. 29, 1947, partitioning Palestine to create a homeland for the Jews, excited Wiesel into action. He found the Paris office of the Irgun newspaper, Zion in Kamf, and offered his services. He was accepted. This is what he writes.8 Whether this is the way it really happened we can’t be sure, knowing as we do how Elie Wiesel throughout his life has played fast and loose with the facts.

Next: Part Two – The activities of the Irgun dominate Wiesel’s life in 1948

Endnotes:

- Elie Wiesel, All Rivers Run to the Sea, Alfred A. Knopf, 1995, 432 pgs.

- Ibid, p 110

- Ibid, p 113

- Hilda DID keep it and showed it at the end of her Shoah Foundation “visual history” interview. I wrote about it and posted the picture here.

- Ibid, p 115

- Warren Routledge writes that Wiesel’s biographer Jack Kolbert changed Francois Wahl’s first name to Gustave, probably because Francois Wahl became well known as a homosexual “since he was 15 years old.”

- Ibid, p 130

- Ibid, p.157

5 Comments

Category Featured | Tags: Tags: All Rivers Run to the Sea, Francois Wahl, Haganah, Irgun, Jewish orphans, Mossad, Oeuvre de Secours, Shushani/Chouchani, sister Bea, sister Hilda, Stern gang, Yiddish typewriter, Ze’ev Jabotinsky, Zion in Kamf,

Social Networks: Facebook, Twitter, Google Bookmarks, del.icio.us, StumbleUpon, Digg, Reddit, Posterous.

Friday, December 24th, 2010

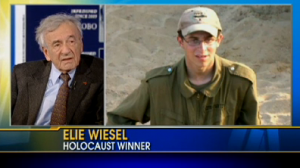

Fox & Friends lets slip what we all know—Wiesel has made a hugely lucrative career out of being a Holocaust survivor. He ‘s a Big Winner in this quite competitive arena, where there are also, in fact, many losers.

Elie Wiesel is making the rounds to promote his new book, so he showed up on Fox & Friends last week. As he was speaking, at 0:57, the words “Elie Wiesel, Holocaust Winner” appear at the bottom of the screen, and at 1:02 it is changed to “Nobel Peace Prize Winner. So it took only a few seconds for the no-doubt-panicked technicians to change it. They might have been out of a job! Dealing with Elie Wiesel is serious business in the media.

You can see the entire interview here in this story from Dec. 22, 2010 at Mediaite.com.