Blog

The Many Faces of Elie Wiesel

Written on September 22, 2010 at 2:55 pm, by admin

By Carolyn Yeager

copyright 2010 Carolyn Yeager

Elie Wiesel has been identified – in some cases has identified himself – in these three photographs. A close examination brings up many questions.

Do any two of these pictures look like the same person? You might think that picture #2 or 3 has a vague resemblance to picture #1, but pictures 2 and 3 don’t in the least resemble each other. The man in picture #2 has a sharp aquiline nose, high cheekbones, full lips and looks quite a bit older than 16 years of age, while the round-headed lad in picture #3 has a wide face, short nose and low forehead. He looks younger than 16.

Picture #2 can be recognized as a close-up from the Famous Buchenwald Liberation Photo. [see page under The Evidence]. Weasel has maintained since the 1980’s that this is his face.

Picture #3 is taken from the photograph below. He is the boy in front of the tall boy in the left column of boys leaving Buchenwald, fourth from the front (the third boy in line is hidden from view). He’s been identified as Elie Wiesel by Prof. Kenneth Waltzer on his Michigan State University website. Wiesel has not denied it. The U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, however, doesn’t claim that Elie is in this picture (see USHMM below).

Above: Children march out of Buchenwald to a nearby American field hospital where they will receive medical care. Buchenwald, Germany, April 27, 1945. — Wide World Photo [Photo and caption from USHMM website]

Below: From Ken Waltzer’s MSU Newsroom Special Report page

Elie Wiesel at Buchenwald

Elie Wiesel is fourth on the left, in front of the tall youth with beret.

Picture courtesy of the late Jack (Yakov) Werber, Great Neck, New York.

Waltzer writes on this same page:

In “Night,” Wiesel says that when he viewed himself in a mirror after liberation, he saw a corpse gazing back at him. But another picture [the one above] taken after liberation on April 17 [he has the date wrong], when the boys were led to the former SS barracks outside the camp, shows Wiesel marching out, fourth on the left, among a phalanx of youth moving together, heads held high, a group together guided by prisoners who had helped save them.

According to Waltzer, Elie Wiesel had a fast recovery to health, body mass and optimism, which Elie himself has never claimed. According to Buchenwald documents, these youths were not sent to France until July 16, 1945 (Fig. 12.4, 12.5),

Waltzer teaches German history and directs the Jewish Studies Program at MSU which includes courses on the Holocaust. He is writing a book about the orphan boys at Buchenwald titled “The Rescue of Children at Buchenwald.” Will Prof. Waltzer offer an explanation in his book for Elie Wiesel’s fit appearance in this photograph? He also accepts the man in the barracks photo as 16-year-old Wiesel. But then he has to, doesn’t he. How will he reconcile these two faces only eleven days apart?

USHMM

The USHMM features the picture shown below on its website—which Waltzer also refers to—and tells us that Elie Wiesel is among these boys without pointing out which one he is. Failing to find anyone who resembles Elie, I wrote to the USHMM asking them to identify him, but received no reply. [Update – because of a reader and also other pictures of Wiesel in France that surfaced later, I now believe Wiesel could be the darkish face in the 2nd to the last row, looking over the shoulder of the boy in a military-looking jacket and to the left of two boys in light-colored caps or berets. ]

Group portrait of Jewish displaced youth at the OSE (Oeuvre de Secours aux Enfants) home for Orthodox Jewish children in Ambloy. Elie Wiesel is among those pictured. Ambloy, France, 1945. — USHMM, courtesy of Willy Fogel

Group portrait of Jewish displaced youth at the OSE (Oeuvre de Secours aux Enfants) home for Orthodox Jewish children in Ambloy. Elie Wiesel is among those pictured. Ambloy, France, 1945. — USHMM, courtesy of Willy Fogel

The U.S. Holocaust Museum dates this picture simply as 1945. It is definitely summer; the boys are dressed in their suits and “traveling clothes,” as if they had just arrived. A large suitcase is being held by a young boy seated in the front row. It fits in every respect the records for the Buchenwald transport that left Germany for France on July 16, 1945.

Wiesel is careful not to give dates for many important events in his memoir All Rivers Run to the Sea. In this book he writes in detail about his trip to France and his early years with the Oeuvre de Secours. Yet he gives not a single date, until he mentions that he first met his future mentor, Shushani, sometime in 1947.1 He writes of being active with the other Jewish youths – engaged in classes, choir practice, trips and flirtations – but strangely not a single photograph is available.

The next picture of Elie Wiesel I have found was taken in 1949. In fact, it is the first picture of him we can be sure of since the 15-year-old portrait of 1944, prior to deportation (picture #1). Why are there no pictures of Wiesel during all the years he was in the Jewish welfare system in France? We are told his sister Hilda, living in Paris, recognized him in 1945 in a photograph of OSE orphans that was published in a newspaper or magazine. What picture was that? [This question was finally answered. See http://www.eliewieseltattoo.com/another-photo-of-young-elie-wiesel-that-is-not-elie-wiesel/ The group photo above? There are no easy or available answers to these questions. It doesn’t take much imagination, however, to consider that it’s because there aren’t any that “fit” the story.

I find it more than ironic that on the page “Elie Wiesel Timeline and World Events, 1928-1951” there are three photographs and Elie Wiesel is not in any one of them!

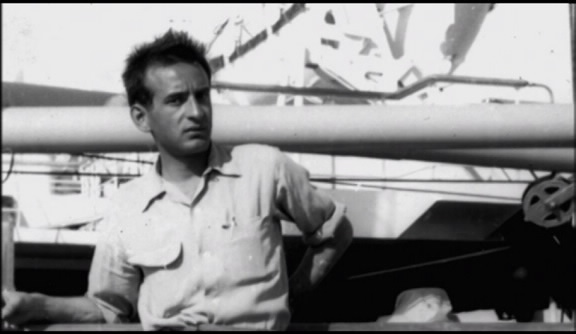

The next picture I can find of Elie Wiesel was taken in 1949, on a ship heading for Israel. We see here the real Elie – long, narrow face, long nose (but not aquiline as in picture #2 above), large ears, high broad forehead, a slender build. He is 20 years old and a journalist, and has probably never looked better. [Maybe that’s why the picture was released.] We learn in his memoir that on May 14, 1948, when David Ben Gurion read out the Israel Declaration of Independence, Elie Wiesel had been working already for around six months for the Irgun Yiddish weekly newspaper Zion in Kamf (Zion in Struggle)– yes, Irgun, the terrorist gang. He remained with the Irgun until they closed their European offices in January 1949. He was then persuaded to go where the action was—to Israel. Helped by the Jewish Agency, and traveling with a few Irgun veterans, he boarded the ship Negba in May or June (uncertain), crossing to Haifa, Israel.2 This picture must have been taken during that trip.

Elie Wiesel on a boat to Israel in 1949

Elie Wiesel on a boat to Israel in 1949

These are the faces of young Elie Wiesel during his “years of travail” that we have at our disposal—not much. I offer the opinion that too much is missing to accept unquestionably the story of his life, during these years 1944-1950, that has been manufactured for public consumption. Only two pictures: before Auschwitz and after his connection with the orphanage was concluded, are definitely him. The search continues.

Endnotes:

- Elie Wiesel, All Rivers Run to the Sea, Alfred Knopf, 1995, p 121.

- ibid, pg. 174-180

Signatures prove Lázár Wiesel is not Elie Wiesel

Written on September 11, 2010 at 4:25 pm, by Carolyn

by Carolyn Yeager

copyright 2010 carolyn yeager

What can be simpler than to compare two signatures of the same name to determine whether they are indeed the same or two different individuals? Fortunately, we have available not only the signature of Elie Wiesel, but also that of Lázár Wiesel. The latter is on the “Military Government of Germany Concentration Camp Inmates Questionnaire.” This Questionnaire (Fragebogen in German) can be seen among The Documents pertaining to the Lazar Wiesel/Elie Wiesel question.

The importance of this lies in the fact that we only have one Lazar Wiesel at a time at Buchenwald, according to the records. Lazar Wiesel, born Sept. 4, 1913 arrived at the camp on January 26, 1945, along with his brother Abram, born Oct. 10, 1900, in a large transport from Auschwitz. They both have Buchenwald registration (or entry) numbers.

After the liberation in April, a questionnaire is filled out by a Lázár Wiesel who accents his name in the Hungarian style, giving a birth date of Oct. 4, 1928, and this Lazar is listed on the “childrens” transport to France in July. Neither of these Lazar Wiesel’s fit Elie Wiesel with his birth date of Sept. 30, 1928, and now I find his signature doesn’t match either.

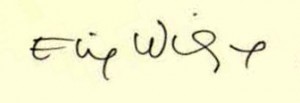

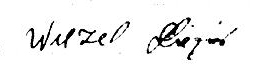

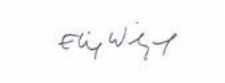

On the left, Elie Wiesel’s well-known signature; on the right, the signature of Lázár Wiesel (last name is written first).

Two more examples of Elie’s book signing. The same style of open, very loose script is also found on the form he filled out for the Yad Vashem Central Database of Shoah Victims, testifying to his father Shlomo’s death at Buchenwald in January 1945. You can view it on their Internet site. Shlomo Vizel is on page 4 of the names.

I suggest that this signature comparison leaves little doubt that the two men are not the same person. Elie Wiesel is NOT the Lázár Wiesel who was liberated from Buchenwald, or who traveled to France with the “Buchenwald Orphans.”1 The young Lázár Wiesel, born Oct. 4, 1928 according to these Buchenwald documents, and whose name and birth date appear on the transport list of “orphaned children” sent from Germany to France in July 1945 (see #14 on The Documents page) has such a visibly different style of writing from the Elie Wiesel who falsely claims to be on that list,2 that the two cannot be confused.

DATES OF ARREST DON’T MATCH

There is more evidence that they are not the same person in the form of the date of arrest shown on the same questionnaire. The date of arrest of Lázár Wiesel is given as April 16, 1944. That is the same day Samuel Jakobovits was arrested. Samuel and Lázár gave each others name as one of three references on their questionnaires, suggesting they were probably friends, or at least acquaintances, that had arrived at the same time.

Myklos Grüner’s date of arrest on his questionnaire is also 16 April 1944, from the city or surrounding area of Nyiregyhaza, Hungary. This can raise a question about the use of April 16 as some kind of “standard” date used by the military authorities in charge of the questionnaires. However, in his book Stolen Identity, Grüner does specify that on April 14, Hungarian gendarmes evacuated the entire population in the ghettos around the city of Nyiregyhaza, approximately 17,000 people. Six days later, “we too were driven from our homes” in Nyiregyhaza to a “holding area” leading to a railway track with a large loading platform, whereupon they boarded a “goods train.” Their destination was Auschwitz-Birkenau, where they would have arrived sometime between April 24 and April 30, 1944 (depending upon how long they stayed in the “holding area” before starting the 3 to 4-day journey).3

By contrast, we know by the authority of Elie Wiesel’s book Night that his family was not arrested on that date. In the “revised and updated” new translation of 2006, Wiesel gives his family’s date of deportation to the “small ghetto” as May 17, 1944. I arrive at this date because Wiesel writes that it was “some two weeks before Shavuot” (Shavuot fell on May 28 in 1944 4) that the deportation order was announced to his family and neighbors. [Remember, Sighet had 90,000 residents, at least one-third of them Jews, while Wiesel makes it sound like he lived in a little village.] Departures were to take place “street by street” starting the next day. That would be May 15. But the Wiesel family was scheduled to leave in the 3rd group, which left two days later, on May 17. After being marched to the “small ghetto,” they stayed there “a few days.” On a “Saturday,” they boarded trains.5 The 20th of May, 1944 was a Saturday

Thus, according to official concentration camp documents and Elie Wiesel’s own testimony, we can demonstrate that Lázár Wiesel was arrested approximately one full month prior to Elie Wiesel being arrested. Elie Wiesel is not the Lázár Wiesel of the Buchenwald documents.

Footnotes:

- Ken Waltzer will present on his book-in-progress, The Rescue of Children and Youth in Buchenwald, at James Madison College on April 11, 2007. In this book, Waltzer explores why, when the U.S. Third Army liberated Buchenwald, April 11, 1945, there were 904 children and youth still alive to be liberated. Among these were Elie Wiesel, a 16-year-old youth from Transylvania, (later Nobel Peace Prize winner) and also Israel Meir Lau, an 8-year-old child from Poland (later Israel Prize winner. http://www.jmc.msu.edu/faculty/show.asp?id=32

- It may be that Elie Wiesel has not made such claims himself, but they have been made by others to support the thesis that he is the one referred to. These others include Ken Waltzer, director of the Jewish Studies Program at Michigan State University, and the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.

- Nikolaus Grüner, Stolen Identity, Stockholm, 2005-2006, pg. 18-19

- “On the second day of Shavuot, 1944 (29 May 1944)” http://www.shtetlinks.jewishgen.org/Vamospercs/

- Elie Wiesel, Night, Hill & Wang, New York, 2006, pg.12-21.

The Shadowy Origins of “Night” III

Written on September 5, 2010 at 2:16 pm, by Carolyn

by Carolyn Yeager

copyright 2010 Carolyn Yeager

Part III: Nine reasons why Elie Wiesel cannot be the author of Un di Velt Hot Gesvign (And the World Remained Silent).

1. The only original source for the existence of an 862-page Yiddish manuscript is Elie Wiesel.

Wiesel’s 1995 memoir All Rivers Run to the Sea is the first time he mentions writing this book in the spring of 1954 on an ocean vessel on his way to Brazil.

In the original English translation of Night, Hill and Wang, 1960, there is no mention of the Yiddish book from whence it came. Nowhere does it name the original version and publication date. There is no preface from the author, only a Foreword by Francois Mauriac who was satisfied to simply call the book a “personal record.”

In his 1979 essay titled “An Interview Unlike Any Other,” Wiesel declares that his first book was written “at the insistence of the French Catholic writer Francois Mauriac” after their first meeting in May 1955. There is no mention in this essay of a Yiddish book, of any length. By “his first book” he obviously meant La Nuit, published in 1958 in France. 38

In his Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech in Dec. 1986, Wiesel doesn’t mention his books, but refers twice to the “Kingdom of Night” that he lived through and once says, “the world did know and remained silent.” So it’s not like he was unaware of this book title. 39

Thus, All Rivers Run appears to be the first mention of the Yiddish origin of Night. Why did Elie Wiesel decide to finally write about And the World Remained Silent in that 1995 memoir? Could it have been because in 1986, after being formally awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in Stockholm, he was “reunited” with a fellow concentration camp inmate Myklos Grüner, who, after that meeting, read the book Night that Wiesel had given him, recognized the identity of his camp friend Lazar Wiesel in it, and from that moment began his investigation of who this man named Elie Wiesel really was?

Grüner writes in his book Stolen Identity, “My work of research to find Lazar Wiesel born on the 4th of September 1913 started first in 1987, to establish contact with the Archives of Buchenwald.” 40 He was also writing to politicians and newspapers in Sweden. This could not have failed to attract the notice of Elie Wiesel and his well-developed public relations network. Grüner tracked down Un di Velt Hot Gesvign as the original book from which Night was taken, and believed it was written by his friend Lazar Wiesel and “stolen” somehow by “Elie.”41

This could account for why Elie Wiesel suddenly began to speak and write about his Yiddish book, published in Buenos Aires, Argentina in 1956. (It was actually inserted into the larger Polish collection in late 1954, according to the Encyclopedia Judaica [see part II], and printed as a single book in 1955, with a 1956 publication date.) 42

Wiesel claims the 862-page typescript he handed over to publisher Mark Turkov on the ship docked at Buenos Aires in spring 1954 was never returned to him.43 (Wiesel had not made a copy for himself, and didn’t ask Turkov to make copies and send him one, according to what he wrote in All Rivers.)

The only other person reported to ever have had the typescript in his hands was Mr. Turkov, but there is no word from him about it. We can only say for sure that he published a 245-page volume in Polish Yiddish titled Un di Velt Hot Gesvign by Eliezer Wiesel. The book has no biographical or introductory material—only the author’s name. Eric Hunt has made this Yiddish book available on the Internet 44 and is seeking a reliable translator.

There is practically nothing written about Mark Turkov. [Added 1-13-25: Since then I have found this: https://congressforjewishculture.org/people/4108/Turkov-Mark-May-11-1904-April-29-1983 in English, with some interesting images -cy] You can read about his accomplished family [there] and here. He was born in 1904 and died 1983. There is no direct testimony from Mark Turkov, that I have been able to find, that he ever received such a manuscript. Since Turkov lived until 1983 to see the book Night become a world-wide best seller, I find this inexplicable. Did no one seek him out to ask him questions, ask for interviews, take his picture? But at the same time, that becomes understandable if Night was not connected with Un di Velt until after 1986 [after Turkov’s death -cy], when Miklos Grüner entered the picture and began asking questions.

We’re left with asking: was there ever an 862 page manuscript? And if not, why does Wiesel say he wrote that many pages?

2. Wiesel could not have written the 862 pages in the time he says he did.

According to what he writes in All Rivers, Wiesel’s voyage lasted at most two weeks. Spending all his time in his cabin, cut off from all sources of information, seemingly on the spur of the moment (not pre-planned), he types feverishly and continuously on a portable typewriter (even though he’s written all his other books in long-hand, by his own testimony) and produces 862 typewritten pages without re-reading a single one. That comes out to an average of almost 62 pages daily, for 14 days straight. Is there anyone who could accomplish such a feat?

The scrawny Elie Wiesel is not a superman; he is not even the intense type, but more of a spaced-out thoughtful type. What’s more, he was not even tired out by this marathon effort, but immediately upon the ship docking at Sao Paulo, he became the active spokesman for a group of “homeless” Jews.

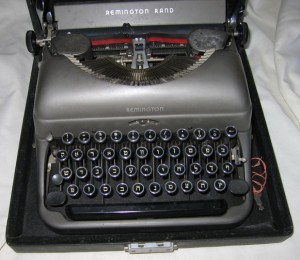

Here is a picture of a Yiddish typewriter from the 1950’s. Notice the red/black ribbon in front of the roller where the paper is inserted.

A point to consider about the typewriter: He would have used up a lot of ribbons typing that many pages. Ribbons are those inked strips of fabric that the metal characters hit to make the black or color impression on the white paper. This is something the computer generation doesn’t know anything about. The ribbons did not last all that long; the characters on the page got lighter as the ribbon was hit again and again; thus he would have been installing a new one with some regularity. As I recall, replacing the ribbon was not a very fun thing to do. Did he plan on writing day and night, and bring plenty of ribbons with him? Was he able to purchase more ribbons for his particular machine in Brazil?

A point to consider about the typewriter: He would have used up a lot of ribbons typing that many pages. Ribbons are those inked strips of fabric that the metal characters hit to make the black or color impression on the white paper. This is something the computer generation doesn’t know anything about. The ribbons did not last all that long; the characters on the page got lighter as the ribbon was hit again and again; thus he would have been installing a new one with some regularity. As I recall, replacing the ribbon was not a very fun thing to do. Did he plan on writing day and night, and bring plenty of ribbons with him? Was he able to purchase more ribbons for his particular machine in Brazil?

Another point about the typewriter brought up earlier by a reader: Was Wiesel a fast or slow typist? Many journalists were, and are, two-fingered (hunt and peck) typists because they never took typing classes. Where would Elie Wiesel have learned to type? In the newspaper office? If he was not a full-finger typist, it’s even less likely he could have churned out all those pages. Not to mention that these old typewriters did not allow the ease, and therefore speed, of our modern [computer] keyboard. These are practical questions that help us to ground ourselves in reality.

In addition, this manuscript is said to have been written in the style of a detailed history of the entire process of deportation, detention, people and places, punishments, liberation, yet Wiesel has no reference materials on board ship—only his memory. And since it was nine years since the events had ended, certainly some dulling of his memory had occurred. This simply could not be accomplished in the kind of mad rush Wiesel describes in All Rivers.

3. Wiesel’s motivation for attempting to write his concentration camp memories when he did is not given and is not apparent.

It’s astonishing that Wiesel gives only one paragraph in his memoir to the entire process of writing this book. He doesn’t write of thinking about it ahead of time. In fact, just at the time of his trip to Brazil he is carrying on a love affair in Paris, as well as being very busy, enthused and ambitious about his journalist assignments. Hanna, his love interest, had proposed marriage to him and he records in All Rivers that it “haunted me during the crossing,” during which time he “was worried sick that I might be making the greatest mistake of my life.”45 Yet, as though a kind of afterthought, he then tells us he spent the entire crossing holed up in his cabin, feverishly writing his very emotionally traumatic “witness” to the holocaust, even though only 9 years of his self-imposed 10-year vow of silence had passed.

In over 100 pages prior to the trip, Wiesel does not mention wanting to write about or even reflecting on his concentration camp year. The only explanation he includes in that paragraph is: “My vow of silence would soon be fulfilled; next year would mark the tenth anniversary of my liberation.”46 Then, just as suddenly, when he steps on land in Brazil, he is fully engaged in journalism and Hanna once again. He has given the typescript away and seems to have totally forgotten about it.

4. Wiesel had no opportunity to edit the 862 pages of And the World Remained Silent to the 245-page published version, yet he says he did.

Wiesel writes in All Rivers, “I had cut down the original manuscript from 862 pages to the 245 of the published Yiddish edition. French publisher Jerome Lindon edited La Nuit down to 178.”47 The time is 1957 and Wiesel is pleased a French publisher has been found for the manuscript he gave to Francois Mauriac—his French translation of Un di Velt Hot Gesvign, of which Wiesel says of the latter, “I had already pruned and abridged considerably.” The publisher, Lindon, now “proposed new cuts throughout, leading to significant differences in length among the successive versions.”

He repeats something similar in his Preface to the new 2006 translation of Night:

Though I made numerous cuts, the original Yiddish version still was long.48

He can only mean the 245-page book as the “original Yiddish version”—thus he “made cuts” from the longer version. But Wiesel could not have done it because he never saw the manuscript again after he supposedly gave it to Mark Turkov. He writes of his extremely busy life following the Brazil trip—covering world events as a journalist, spending time in Israel again before considering moving to NYC. He sounds underwhelmed when he reports receiving a copy of the Yiddish book in the mail from Turkov in Dec.1955, and devotes only a couple sentences to it. 49

Another time he refers to reducing the 245-page Yiddish version into a French version. Speaking of Mauriac:

He was the first person to read Night after I reworked it from the original Yiddish. 50

It is just these kinds of comments that cause the confusion remarked upon by Naomi Siedman in her essay commenting on Jewish rage in Wiesel’s first book. She writes that certain “scholars,” such as Ellen Fine and David Roskies give conflicting reports on the length of Wiesel’s original book, and it’s not clear just which book they are talking about. In my opinion, the reason for all the confusion is that they take Wiesel at his word as an honest witness … perhaps with some memory lapses. They won’t entertain the idea that this is part of a cover-up, the details of which Mr. Wiesel has a hard time keeping straight.

5. Wiesel’s recognized “style” and the style of the Yiddish book are noticeably different.

Not enough is known as yet to non-Yiddish readers like me about the content of Un di Velt Hot Gesvign to make the strongest case for the above statement, but a Jewish critic has provided some passages from the Yiddish book and I will quote from her (except for one passage from Joachim Neander). Naomi Siedman, in her long essay cited above, says this:

For the Yiddish reader, Eliezer Wiesel’s memoir was one among many, valuable for its contributing an account of what was certainly an unusual circumstance among East European Jews: their ignorance, as late as the spring of 1944, of the scale and nature of the Germans’ genocidal intentions. 51

In other words, holocaust narratives had already developed a “Yiddish genre” and the Wiesel memoir fit in with them. She explains:

When Un di velt had been published in 1956, it was volume 117 of Turkov’s series, which included more than a few Holocaust memoirs. The first pages of the Yiddish book provide a list of previous volumes (a remarkable number of them marked “Sold out”), and the book concludes with an advertisement/review for volumes 95-96 of the series, Jonas Turkov’s Extinguished Stars. In praising this memoir, the reviewer implicitly provides us with a glimpse of the conventions of the growing genre of Yiddish Holocaust memoir. Among the virtues of Turkov’s work, the reviewer writes, is its comprehensiveness, the thoroughness of its documentation not only of the genocide but also, of its victims.

[…]

Thus, whereas the first page of Night succinctly and picturesquely describes Sighet as “that little town in Transylvania where I spent my childhood,” Un di Velt introduces Sighet as “the most important city [shtot] and the one with the largest Jewish population in the province of Marmarosh,” and also “Until, the First World War, Sighet belonged to Austro-Hungary. Then it became part of Romania. In 1940, Hungary acquired it again.” 52

The Yiddish book has a different “feel” to it from Night; not only a different style, but a different personality is behind it. Ms. Seidman told E.J. Kessler, editor of The Forward:

The two stories can be reconciled in strict terms,” she said, “but they still give two totally different impressions, one of a person who’s desperate to speak versus one who’s reluctant.53

Here is a translation by Dr. Joachim Neander of a key passage in the Yiddish book, which he posted on the CODOH forum. It reveals an informal, talkative style, totally different from the spare, literary style used by Wiesel in all his books, even though the storyline is basically the same. Wiesel says he edited this book to its published form, but it doesn’t sound like him.

On January 15, my right foot began to swell. Probably from the cold. I felt horrible pain. I could not walk a few steps. I went to the hospital. The doctor examined the swollen foot and said: It must be operated. If you will wait longer, he said, your toes will have to be cut off and then the whole foot will have to be amputated. That was all I needed! Even in normal times, I was afraid of surgery. Because of the blood. Because of bodily pain. And now – under these circumstances! Indeed, we had really great doctors in the camp. The most famous specialists from Europe. But the means they had to their disposition were poor, miserable. The Germans were not interested in curing sick prisoners. Just the opposite.

If it had been dependent on me, I would not have agreed to the operation. I would have liked to wait. But it did not depend on me. I was not asked at all. The doctor decided to operate, and that was it. The choice was in his hands, not in mine. I really felt a little bit of joy in my heart that he had decided upon me.54

Back to Siedman’s translations. Two examples will have to suffice, from the Dedication and the very last paragraphs.

… while the French memoir is dedicated “in memory of my parents and of my little sister, Tsipora,” the Yiddish names both victims and perpetrators: “This book is dedicated to the eternal memory of my mother Sarah, father Shlomo, and my little sister Tsipora — who were killed by the German murderers.” 55

Now the book’s ending in the Yiddish version:

Three days after liberation I became very ill; food-poisoning. They took me to the hospital and the doctors said that I was gone. For two weeks I lay in the hospital between life and death. My situation grew worse from day to day.

One fine day I got up — with the last of my energy — and went over to the mirror that was hanging on the wall. I wanted to see myself. I had not seen myself since the ghetto. From the mirror a skeleton gazed out. Skin and bones. I saw the image of myself after my death. It was at that instant that the will to live was awakened. Without knowing why, I raised a balled-up fist and smashed the mirror, breaking the image that lived within it. And then — I fainted. From that moment on my health began to improve. I stayed in bed for a few more days, in the course of which I wrote the outline of the book you are holding in your hand, dear reader.

But — Now, ten years after Buchenwald, I see that the world is forgetting. Germany is a sovereign state, the German army has been reborn. The bestial sadist of Buchenwald, Ilsa Koch, is happily raising her children. War criminals stroll in the streets of Hamburg and Munich. The past has been erased. Forgotten. Germans and anti-Semites persuade the world that the story of the six million Jewish martyrs is a fantasy, and the naive world will probably believe them, if not today, then tomorrow or the next day.

So I thought it would be a good idea to publish a book based on the notes I wrote in Buchenwald. I am not so naive to believe that this book will change history or shake people’s beliefs. Books no longer have the power they once had. Those who were silent yesterday will also be silent tomorrow. I often ask myself, now, ten years after Buchenwald: Was it worth breaking that mirror? Was it worth it? 56

In contrast, Night ends with the gaze into the mirror at the very beginning of this passage. If the smashing of the mirror and the renewed will to live he felt from it was Elie Wiesel’s own experience, why would he leave it out in La Nuit? Because the publisher wanted it out? Not at all likely. Mauriac? Doubtful. It’s much more likely that it was not Elie Wiesel’s experience and it was not the kind of story he felt he could or wanted to tell.

Also note that the Yiddish writer says he wrote the outline of the book while still in the Buchenwald hospital, and that the published book is based on those notes. Elie Wiesel has never suggested that he began any writing in Buchenwald.

6. Wiesel wrote only one book in Yiddish; all subsequent books are in French.

If we could ask Elie Wiesel why he wrote his concentration camp memoirs in Yiddish, when he was already fluent and writing in French, we would probably get the answer he gave to his friend Jack Kolbert, who was writing a book about him:

“I wrote my first book, Night, in Yiddish, a tribute to the language of those communities that were killed. I began writing it in 1955. I felt I needed ten years to collect words and the silence in them.” 57

Alright. But we should also ask, just how good was Wiesel’s written Yiddish, that he could write this “enormous tome” in such a short time? After Nov. 29, 1947, Wiesel sought out and was given a job with the Irgun Yiddish weekly in Paris called Zion in Kamf. He tells how he was put to work translating Hebrew into Yiddish.

The task was far from easy. I read Hebrew well and spoke fluent Yiddish, but my Germanized written Yiddish wasn’t good. My style was dry and lifeless, and the meaning seemed to wander off into byways lined with dead trees. That was not surprising, since I was wholly ignorant of Yiddish grammar and its vast, rich literature.58

Even though he continued to translate and eventually write for the paper, he also spoke and wrote otherwise in French. He was attending classes at the Sorbonne and reading French classics and the newer existentialists. Following this first and only Yiddish book, Wiesel has done all his writing in French, by his own account—and in longhand, while the Yiddish was written on a typewriter.

It’s hard to reconcile Wiesel’s professed love of Yiddish 59 with his failure to do any writing beyond Un di Velt in that language. It’s suggested it is because Yiddish readers are a diminishing breed. No doubt, but that was already the case in 1954. For what it’s worth, Myklos Gruner records that when he met Elie Wiesel at their pre-arranged encounter in Stockholm in 1986, he asked Elie if he would like to speak in “Jewish,” and Elie said “no.” They ended up speaking together in English.60 Wiesel seems to have no interest in keeping the language alive.

7. Wiesel gives contradictory dates for the writing of his first book, and is fuzzy about what his “first book” is.

Wiesel makes it definite in All Rivers that he wrote the Yiddish book in the spring of 1954, in a cabin of a ship going to Brazil. But around the year 2000 he tells his friend Jack Kolbert:

It took me 10 years before I felt I was ready to do it. I wrote my first book, Night, in Yiddish, a tribute to the language of those communities that were killed. I began writing it in 1955. I felt I needed ten years to collect words and the silence in them. 61

So, is it 1954 or 1955? Wiesel says in All Rivers he met Francois Mauriac in May 1955, one year after his Brazil trip. Mauriac is often credited as the one who convinced Wiesel to end his silence, which culminated in Night. In his 1979 essay, “An Interview Unlike Any Other,” Wiesel writes:

Ten years of preparation, ten years of silence. It was thanks to Francois Mauriac that, released from my oath, I could begin to tell my story aloud. I owe him much, as do many other writers whose early efforts he encouraged. But in my case, something totally different and far more essential than literary encouragement was involved. That I should say what I had to say, that my voice be heard, was as important to him as it was to me.

[…]

(H)e urged me to write, in a display of trust that may have been meant to prove that it is sometimes given to men with nothing in common, not even suffering, to transcend themselves.62

He also wrote, in the same essay on the next page (17):

Paris 1954. As correspondent for the Israeli newspaper Yedioth Ahronoth, I was trying to move heaven and earth to obtain an interview with Pierre Mendes-France, who had just won his wager by ending the Indochina war. Unfortunately, he rarely granted interviews, choosing instead to reach the public with regular talks on the radio. Ignoring my explanations, my employer in Tel Aviv was bombarding me with progressively more insistent cabled reminders, forcing me to persevere, hoping for a miracle, but without much conviction. One day I had an idea. Knowing the admiration the Jewish Prime Minister bore the illustrious Catholic member of the Academie, why not ask the one to introduce me to the other? The occasion presented itself. I attended a reception at the Israeli Embassy. Francois Mauriac was there. Overcoming my almost pathological shyness, I approached him, and in the professional tone of a reporter, requested an interview. It was granted graciously and at once.

Wiesel continues the confusion around ’54 and ’55 when interviewed by the American Academy of Achievement on June 29, 1996 in Sun Valley, Idaho.63 In answer to the question “What persuaded you to break that silence?” he replied:

Oh, I knew ten years later I would do something. I had to tell the story. I was a young journalist in Paris. I wanted to meet the Prime Minister of France for my paper. He was, then, a Jew called Mendès-France. But he didn’t offer to see me. I had heard that the French author François Mauriac […] was his teacher. So I would go to Mauriac, the writer, and I would ask him to introduce me to Mendès-France. […]

Pierre Mendes-France became Prime Minister on June 18, 1954; his hold on that office ended on Jan. 20, 1955. Wiesel, according to his autobiography, had returned from Brazil, after writing and giving his 862-page Yiddish manuscript to Mark Turkov, expressly to cover the inauguration of France’s new Prime Minister for his Israeli newspaper.64 In this case, Wiesel’s first meeting with Mauriac had to be some time after mid-June 1954, since Mendes-France is already Prime Minister; it couldn’t have been in May or June 1955 because Mendes-France was long out of office. But in All Rivers, he puts his first Mauriac meeting in May 1955: “I first saw Mauriac in 1955 during an Independence Day celebration at the Israeli embassy.”(p.258) Israel’s Independence Day is May 14. Wiesel says the interview with Mauriac he obtained from that meeting resulted in his writing La Nuit and sending it to Mauriac one year later, in 1956. He continues describing that meeting to the Academy interviewer:

I closed my notebook and went to the elevator. He (Mauriac) ran after me. He pulled me back; he sat down in his chair, and I in mine, and he began weeping. […] And then, at the end, without saying anything, he simply said, “You know, maybe you should talk about it.”

He took me to the elevator and embraced me. And that year, the tenth year, I began writing my narrative. After it was translated from Yiddish into French, I sent it to him.

Wiesel says “the tenth year,” which would be 1955, but in the earlier part of the interview he is referring to 1954—because of Mendes-France. Snce he is mixing up the date, it’s no wonder we find the same mis-dating in stories about Wiesel’s life and accomplishments in books and on the Internet, including on Wikipedia pages.

Whenever it was that Wiesel had that fateful visit with Mauriac, he clearly did not mention that he had already written a very long Yiddish memoir, whether a year or a couple of months earlier. But had he written anything yet? Mauriac never alludes to a first Yiddish text. And as stated before, Wiesel himself didn’t either, until his 1995 memoir All Rivers Run to the Sea. This is truly noteworthy. Also, the title Un di Velt Hot Gesvign or, in English, And the World Remained Silent does not appear on the long list of “books by Elie Wiesel” at the beginning of All Rivers or the 2006 translation of Night.

To clarify an important problem Wiesel faces here: Wiesel, prior to 1990, claims to have first met and interviewed Mauriac in the spring of 1954 after returning from Brazil, but later changed it to May or June 1955. But even after that, he sometimes reverted to the 1954 scenario. When you are inventing all or parts of your life story, it’s difficult to keep it straight, especially when your guard is down.

A likely reason is his need to fit the writing and publication of the Yiddish book into his “schedule”, something he had not considered, or just ignored, previous to the Yiddish book being brought to the attention of the world by Myklos Grüner .

8. There are striking differences between Night, his “true story” derived from the Yiddish book, and his autobiography All Rivers Run to the Sea.

If Night is a true account of Wiesel’s holocaust experience, how to explain such major differences in the key passages that are compared below. In the first book it is his foot, in the latter his knee that is operated on right before the 1945 evacuation of Auschwitz.

Toward the middle of January, my right foot began to swell because of the cold. I was unable to put it on the ground. I went to have it examined. The doctor, a great Jewish doctor, a prisoner like ourselves, was quite definite: I must have an operation! If we waited, the toes—and perhaps the whole leg—would have to be amputated. .65

[…]

The doctor came to tell me that the operation would be the next day […] The operation lasted an hour.66

The doctor told him he would stay in the hospital for two weeks, until he was completely recovered. The sole of his foot had been full of pus; they just had to open the swelling. But, two days after his operation there was a rumor going round the camp that the Red Army was advancing on Buna. Not able to decide whether to stay in the hospital or join the evacuation, he left to look for his father.

“My wound was open and bleeding; the snow had grown red where I had trodden.” That night his “foot felt as if it were burning.” In the morning, he “tore up a blanket and wrapped my wounded foot in it.” 67

He and his father decided to leave. That night they marched out. They were forced to run much of the night and he ran on that foot, causing great pain. But after that he doesn’t mention it again. By contrast, in All Rivers, it is not his foot, but his knee that is operated on!

January 1945. Every January carried me back to that one. I was sick. My knee was swollen, and the pain turned my gait into a limp. […] That evening before roll call, I went to the KB. My father waited for me outside […] At last my turn came. A doctor glanced at my knee, touched it. I stifled a scream. “You need an operation,” he said. “Immediately.” […] One of the doctors, a tall, kind-looking man, tried to comfort me. “It won’t hurt, or not much anyway. Don’t worry, my boy, you’ll live.” He talked to me before the operation, and I heard him again when I woke up.” 68

[…]

January 18, 1945. The Red Army is a few kilometers from Auschwitz. […] My father came to see me in the hospital. I told him the patients would be allowed to stay in the KB […] and he could stay with me […] but, finally, we decided to leave with the others, especially since most of the doctors were being evacuated too.69

No further mention of the knee. How can we account for this bizarre change from foot to knee? It seems that as weak as Wiesel presents himself to be at Buna, he could not himself believe that he could run around on a foot that had just been operated on for pus in the sole, with no protection. So he simply changed it to his knee.

The next passage is after the liberation of Buchenwald on April 11, 1945. In Night:

Our first act as free men was to throw ourselves onto the provisions. We thought only of that. Not of revenge, not of our families. Nothing but bread.

And even when we were no longer hungry, there was still no one who thought of revenge. On the following day, some of the young men went to Weimar to get some potatoes and clothes—and to sleep with girls. But of revenge, not a sign.

Three days after the liberation of Buchenwald I became very ill with food poisoning. I was transferred to the hospital and spent two weeks between life and death.70

In All Rivers, Wiesel changes the story. He writes:

A soldier threw us some cans of food. I caught one and opened it. It was lard, but I didn’t know that.71 Unbearably hungry—I had not eaten since April 5—I stared at the can and was about to taste its contents, but just as my tongue touched it I lost consciousness.

I spent several days in the hospital (the former SS hospital) in a semiconscious state. When I was discharged, I felt drained. It took all my mental resources to figure out where I was. I knew my father was dead. My mother was probably dead ….. 72

From two weeks to only several days spent in the hospital. Could this change have anything to do with the famous “Buchenwald survivor” photograph73 that Elie discovered himself in sometime after 1980, when he was actively seeking a Nobel Prize? If he were in the hospital “between life and death” for two weeks following April 14 or so, he could not be in that photograph taken on April 16. The author of And the World Remained Silent, whoever he is, never claimed to be in that photograph.

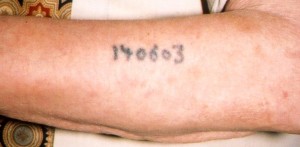

9. Elie Wiesel refuses to back up his authorship by showing his tattoo.

If Elie Wiesel is the man who wrote Un di Velt Hot Gesvign, the source of the world-famous Night—the same man who wrote about receiving the tattoo number A7713 at Auschwitz in 1944—why won’t he show us this tattoo on his arm? And why do we see video of his left forearm with no tattoo visible at all? Wiesel could so easily clear up this problem, but he doesn’t choose to do so.

Endnotes:

38) Elie Wiesel, A Jew Today, Vintage Books, 1979, 260 pg.

39) http://worldsgreatestenglishclass.com/media/ww2/19EWSpeech.pdf

40) Stolen Identity, p. 50

41) Ibid, p. 43. Grüner mentions the 862 pages twice, but not with proof of their existence. “… Lazar Wiesel’s manuscript […] tell us his story and covers his survival of the Holocaust in 862 pages.” Also, “… had to use Lazar’s false identity in Paris and his existing manuscript of 862 pages …”

42) All Rivers, p. 277. “In December (1955) I received from Buenos Aires the first copy of my Yiddish testimony And the World Stayed Silent,” which I had finished on the boat to Brazil.”

43) Ibid.

44) http://rapidshare.com/files/441835370/Elie-Wiesel-Night-Yiddish.pdf

45) All Rivers, p. 239

46) Ibid, p. 240

47) Ibid, p. 319

48) Night, p. x

49) All Rivers, p. 277

50) Ibid. p. 267

51) Siedman, “Jewish Rage”

52) Ibid.

53) “The Rage that Elie Wiesel Edited Out of Night,” E.J. Kessler, ‘The Forward‘, October 4, 1996

54) http://forum.codoh.com/viewtopic.php?f=2&t=6146

55) Siedman, “Jewish Rage,” (trans. from Un di Velt)

56) Ibid. (Un di Velt, 244-45)

57) Jack Kolbert, The Worlds of Elie Wiesel: An Overview of His Career and His Major Themes, Susquehanna University Press, Selinsgrove, PA, 2001, p. 29

58) All Rivers, p.163

59) Ibid. p.291-92

60) Stolen Identity, p.31

61) Kolbert, p. 29

62) “An Interview Unlike Any Other,” Elie Wiesel, A Jew Today, trans. Marion Wiesel (New York, 1979), p.16

63) http://www.achievement.org/autodoc/page/wie0int-3

64) All Rivers, p. 242: “I had been away for two months when Dov recalled me to Paris to cover Pierre Mendes-France’s accession to power. I flew back …” This had to be in June 1954.

65) Night, p.82

66) Ibid. p.83

67) Ibid. p.87

68) All Rivers, p.89-90

69) Ibid. p.91

70) Night, p.115-16

71) Why would soldiers throw cans of lard? Sounds terribly disorganized and irregular. How did he open the can? If he didn’t know it was lard, and lost consciousness before he tasted it, we must assume someone in the hospital told him after he regained consciousness that he had been holding a can of lard when he was brought in. Either that or it’s just made up.

72) All Rivers, p.97

73) http://www.eliewieseltattoo.com/buchenwald

Is Elie Wiesel a perjurer?

Written on August 24, 2010 at 10:01 am, by Carolyn

By Carolyn Yeager

Elie Wiesel stated under oath while giving testimony in the trial of Eric Hunt in San Francisco, California in July 2008 that the number A7713 was tattooed on his left arm. (see Where is the Tattoo? on this site)

Wiesel should have been asked to show his tattoo to the court at that time, but he wasn’t. This was a failure of the defense, for sure. But obviously, at that time, Mr. Hunt, the defendant, was not questioning whether Elie Wiesel had been an inmate of Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Since then, Mr. Hunt and others have uncovered video photography of Wiesel’s bare left arm from all angles, leaving no reasonable doubt that no tattoo is there. Backing up this conclusion is the fact that Wiesel has also famously refused to ever show his tattoo when requested to do so. For those who will retaliate that Wiesel may have had the tattoo removed, he said as late as March 25, 2010 that he still had the number A7713 on his arm. (see Where is the Tattoo?)

From this, the average man on the street would probably agree that Elie Wiesel has committed perjury (a criminal offense) if he does not indeed have the number tattooed on his arm. The law, according to http://www.lectlaw.com/def2/p032.htm, says:

When a person, having taken an oath before a competent tribunal, officer, or person, in any case in which a law of the U.S. authorizes an oath to be administered, that he will testify, declare, depose, or certify truly, or that any written testimony, declaration, deposition, or certificate by him subscribed, is true, willfully and contrary to such oath states or subscribes any material matter which he does not believe to be true; or in any declaration, certificate, verification, or statement under penalty of perjury, willfully subscribes as true any material matter which he does not believe to be true; (18 USC )

In order for a person to be found guilty of perjury the government must prove: the person testified under oath before [e.g., the grand jury]; at least one particular statement was false; and the person knew at the time the testimony was false.

However, in practice, the question of materiality is crucial. Perjury is defined at Criminal-law.freeadvice.com as:

the “willful and corrupt taking of a false oath in regard to a material matter in a judicial proceeding.” It is sometimes called “lying under oath;” that is, deliberately telling a lie in a courtroom proceeding after having taken an oath to tell the truth. It is important that the false statement be material to the case at hand—that it could affect the outcome of the case. It is not considered perjury, for example, to lie about your age, unless your age is a key factor in proving the case.

So the question becomes: Was the status of Elie Wiesel as a survivor of at least a seven-month incarceration at Auschwitz-Birkenau in 1944-45, in which case he would certainly have been tattooed on his left arm, as he states himself, material to the guilt or innocence of Eric Hunt in light of the charges that had been brought against him? Certainly, Eric Hunt, not long out of college at the time and who had been assigned to read Night in school, had come to doubt the truth of Wiesel’s assertions and descriptions in the book, and believed that if he could confront Wiesel alone, unguarded, he could convince him to tell the truth.

Does the suspicion that Wiesel necessarily lied in his book Night about what he saw and experienced at Auschwitz-Birkenau because he lied about the existence of a tattoo which he has always claimed as proof of his credentials as an Auschwitz survivor, exonerate Eric Hunt from some of the charges brought against him by the State of California? Is it material to the case? Perhaps not, but it does show cause for Eric Hunt’s desire to speak to Elie Wiesel in an unguarded moment, which was what he was attempting to do.

If Elie Wiesel cannot be legally found guilty of perjury because of questions of materiality, he will certainly be guilty of perjury in the eyes of the public if he does not produce the famous tattoo A-7713 on his arm—the sooner the better. We are waiting, Mr. Wiesel.

Watch a new, short video on the subject.

Addendum:

”Auschwitz survivor Sam Rosenzweig displays his identification tattoo.” From Wikipedia According to the information below, this man was in the “regular” series—numbers not preceeded with a letter of the alphabet. Note also that the tattoo is on the outside of the left forearm.

”Auschwitz survivor Sam Rosenzweig displays his identification tattoo.” From Wikipedia According to the information below, this man was in the “regular” series—numbers not preceeded with a letter of the alphabet. Note also that the tattoo is on the outside of the left forearm.

This is the best looking tattoo I could find on the Internet. If you want to have your faith in the Auschwitz Holocaust story badly shaken, google “Auschwitz tattoos” (or any variation thereof) – Images, and see what comes up. Frightening! Of the little that is there, most look like the numbers are way too big, and you find the same few people exhibiting their specimen.

However … George Rosenthal, Trenton, NJ, an Auschwitz Survivor, has written an “authoritative” account at Jewish Virtual Library based on “documents” obtained from The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. (Sorry, no pictures here either, or on the USHMM website. Elie Wiesel was a major driving force in the creationof the USHMM; why didn’t he volunteer his tattoo to be pictured on their website as an example of what a genuine tattoo looks like? Why does the USHMM have no images of a tattoo?)

Mr. Rosenthal writes:

The sequence according to which serial numbers were issued evolved over time. The numbering scheme was divided into “regular,” AU, Z, EH, A, and B series’. The “regular” series consisted of a consecutive numerical series that was used, in the early phase of the Auschwitz concentration camp, to identify Poles, Jews, and most other prisoners (all male). This series was used from May 1940-January 1945, although the population that it identified evolved over time. Following the introduction of other categories of prisoners into the camp, the numbering scheme became more complex. The “AU” series denoted Soviet prisoners of war, while the “Z” series (with the “Z” standing for the German word for Gypsy, Zigeuner) designated the Romany. These identifying letters preceded the tattooed serial numbers after they were instituted. “EH” designated prisoners that had been sent for “reeducation” (Erziehungshäftlinge).

In May 1944, numbers in the “A” series and the “B” series were first issued to Jewish prisoners, beginning with the men on May 13th and the women on May 16th. The “A” series was to be completed with 20,000; however an error led to the women being numbered to 25,378 before the “B” series was begun. The intention was to work through the entire alphabet with 20,000 numbers being issued in each letter series. In each series, men and women had their own separate numerical series, ostensibly beginning with number 1.

According to this, since there was never a “C” series, the maximum number of prisoners that could have been tattooed after May 1944 was 45,378.

Under “Notes” at the bottom of the page, four books are listed, all by holocaust historians. Are these the “documents” referred to? It also says Source: Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies at the very bottom of the page, as if referring to the entire page. This Center is located at the University of Minnesota. The affiliated faculty reveals mostly Jewish names.

I report all this because I’m looking for authoritative sources for the exact placement of the tattoos on the left arm, but one doesn’t find that answer even at the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial Museum. Why all the uncertainty? Could it be because so many pseudo-survivors have tattooed themselves in unusual ways and places, and the authorities don’t want to nullify their legitimacy?

Wiesel to accept first World Jewish Congress “Guardian of Jerusalem” award

Written on August 22, 2010 at 12:06 pm, by Carolyn

Jews from around the world gather in Jerusalem on Aug. 31-Sept. 1, 2010 to focus attention on what they call “threats against Israel .” Elie Wiesel will be presented with the first WJC “Guardian of Jerusalem” award in recognition of his lifetime efforts “on behalf of the Jewish people.” The Israeli emergency rescue operation in Haiti will also be recognized. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, Defense Minister Ehud Barak, along with many other Israeli notables will participate in this effort to counter the intensifying world disapproval of Israel ’s policies. Read more