Blog

Wiesel Contradicts Himself to Chapman Students

Written on April 4, 2011 at 8:43 am, by Carolyn

By Carolyn Yeager

Cliches are all Chapman students get from the Master of Platitudes’much-ballyhooed visit. Above: Elie Wiesel looks frail in this group photo taken after he spoke to students at the Sala and Aron Samueli Holocaust Memorial Library at Chapman University. (Photo credit: Orange Country Register)

Above: Elie Wiesel looks frail in this group photo taken after he spoke to students at the Sala and Aron Samueli Holocaust Memorial Library at Chapman University. (Photo credit: Orange Country Register)

The Los Angeles Times sent its own reporter to cover the Holocaust Hero’s grand arrival at Chapman University during the first week of April. The Local section of the newspaper had a report on Wiesel’s visit with 21 students in the specialized Holocaust Library on the campus.

Wiesel has fewer answers these days (not much is expected of him) and speaks in a sort of cliché-language that he has mastered. He can be confident his listeners will supply a profound meaning to any utterance that comes forth from his mouth. For example:

One (student) wanted to know how Wiesel managed to overcome the memories of the deaths of his father, mother and sister to write his first book, “Night,” an autobiographical account of … Nazi concentration camps.

With deep sadness in his eyes, Wiesel replied, “Only those who were there know what it was like. We must bear witness. Silence is not an option.”

Wiesel did not really like this question and gave a short answer that was not an answer at all. The question was: How did he overcome the [painful] memories in order to write his book? His actual answer, interpreted, was: “I won’t, or I can’t, answer your question.” We can ask why he won’t answer that question, and also why he has not ever answered that question. Could it be because he has no idea how to answer it since such a thing did not actually happen to him?

To make it sound like he’s giving some kind of answer, he adds two things that have nothing to do with the question: “We must bear witness” and “Silence is not an option.” These are both favorite sayings typically associated with him. Upon hearing him say them, his listeners are satisfied that they are hearing the real Wiesel, that they are blessed by a “transforming” moment.

Another question was more to Wiesel’s liking. “How can this generation preserve what you learned there?”

Wiesel brightened as he said, “Listen to the survivors. They are an endangered species now. This is the last chance you have to listen to them. I believe with all my heart that whoever listens to a witness becomes a witness. Once we have heard, we must not stand idly by. Indifference to evil makes evil stronger.”

More platitudes. But a reader brought to my attention that Wiesel is contradicting something he said on another occasion. Even though we know contradictions are the usual fare from this man, it’s of note that in a 1978 interview with the New York Times, Wiesel pronounced:

“The Holocaust [is] the ultimate event, the ultimate mystery, never to be comprehended or transmitted. Only those who were there know what it was; the others will never know.”*

This fits his first answer, but not his second. So, is it that “only those who were there know what it was like” (meaning it’s impossible to transmit to others), or is it that we can all “become a witness” (and speak with authority about what it was like)?

If you really want the truthful answer, dear readers, it is whatever benefits the Holocaust Industry. That is the whole reason Elie Wiesel goes to Chapman University—to create publicity for Holocaustianity—since he adds no real value to the students’ learning. Still, it’s all taken very solemnly by the faculty, the mainstream media, and the impoverished students themselves, who don’t realize how they’re being cheated. In a university setting, they are expected to swallow whole whatever they hear from iconic sources re the holocaust. The real questions they have are not answered. It is a farce of education. This Presidential Fellowship shows us once again, when it comes to Elie Wiesel it is always “much ado about nothing.”

*Elie Wiesel, “Trivializing the Holocaust”, New York Times, 16 April 1978, p. 2:1 [Article written in response to the original airing of the NBC miniseries The Holocaust]; quoted in Peter Novick, The Holocaust in American Life, 1999, p. 211.

Elie Wiesel and Chapman University need help with “knowledge and ethics” surrounding the holocaust

Written on March 30, 2011 at 1:18 pm, by Carolyn

by Carolyn Yeager

Elie Wiesel arrived at Chapman University in Orange CA on Monday, March 28 in his new capacity as “Distinguished Presidential Fellow” and gave a lecture titled “Knowledge and Ethics.” He also spoke to a small class of Chapman Religion students. According to the Orange County Register [photo at right courtesy Paul Bersbach, OCR], he “answered several questions, but posed many of his own.” This is typically the way Wiesel, 82, avoids revealing his ignorance of the entire topic of the concentration camps.

Elie Wiesel arrived at Chapman University in Orange CA on Monday, March 28 in his new capacity as “Distinguished Presidential Fellow” and gave a lecture titled “Knowledge and Ethics.” He also spoke to a small class of Chapman Religion students. According to the Orange County Register [photo at right courtesy Paul Bersbach, OCR], he “answered several questions, but posed many of his own.” This is typically the way Wiesel, 82, avoids revealing his ignorance of the entire topic of the concentration camps.

Wiesel’s contract with the university, and specifically with the Rodgers Center for Holocaust Education which is the real sponsor and driving force behind the contract, is for five years. Thanks to a bequest from Barry and Phyllis Rodgers, the Rodgers Center was opened in 2000 for the purpose of helping to keep the memory of the holocaust alive, well, and lucrative.

As we reported here last October, each spring semester Wiesel will deliver a lecture and carry on some interaction with students. Don’t think he’s doing it only in the interest of “keeping memory alive” or for any of the noble reasons suggested by Marilyn Harran, Director of the Rodgers Center and University spokesperson on matters pertaining to Wiesel’s fellowship.

Left: Marilyn Harran. Right: Wilkinson Hall on the Chapman campus. The Rodger Center comes under the aegis of the Wilkinson College of Humanities and Social Studies.

As reported in the Chapman Panther newspaper on March 28, “Harran declined to say how much the Rodgers Center is paying Wiesel for his lecture. Mary Platt, director of communications and media relations, confirmed that the amount is confidential.”

It’s widely quoted that Wiesel’s standard speaking fee is $25,000. We don’t know how much he is charging for visiting with students in their classrooms, but it is no doubt substantial. Chapman’s wealthy Jewish donors who support activities at the special Rodgers Center for Holocaust Education and the Samueli Holocaust Memorial Library are apparently willing to pay it.

Harran, a professor in both the Religious Studies and History departments, is a devotee of Wiesel and his myth. She tends to speak of Wiesel in worshipful terms, as I reported in my Oct. 2010 blog post. At that time, she included these words in her announcement of his fellowship at Chapman: “We are unbelievably fortunate that he has chosen to return to Chapman and to share with us his knowledge and wisdom. I am stunned and deeply grateful that he will be with us in this new role as Distinguished Presidential Fellow. I know our university community will be profoundly enriched and inspired by his presence.” This is the cue for students to show the proper respect toward the visiting professor, and hang on his every word.

Harran is teaching a course this semester called “Elie Wiesel: His Life and Work” with Jan Osborn, professor of English. According to The Panther, only eighteen students are taking the course. Harran wrote a March 28th opinion piece for the school newspaper titled “Knowledge, ethics and Elie Wiesel” in which she mentioned his book Night and also said: “Some of you will recall seeing Wiesel visiting Auschwitz with Oprah Winfrey or standing by President Obama’s side at a commemorative ceremony in Buchenwald. These are powerful images. Indeed, it is hard to remember when the memory of the Holocaust did not have a place in our American life and culture. There are Holocaust documentaries and films; Holocaust museums in cities such as Chicago, Houston and Los Angeles, and the Sala and Aron Samueli Holocaust Memorial Library at Chapman. And there is the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C.”

Hurrah, hurrah. Isn’t it wonderful. She gives Wiesel much of the credit for bringing this about. She then asserts this historical tidbit: “the Final Solution was agreed upon in a 90-minute meeting attended by 15 senior SS officials and bureaucrats”—referring to the reputed “Wannsee Conference” in 1942 in Germany. But the meeting minutes show clearly that it was a discussion of the “final solution of the Jewish problem” as a deportation plan, not an extermination plan. So where does that leave Elie Wiesel’s story? And Harran is a PhD in History? It’s obvious she needs some help with knowledge and ethics herself.

Wiesel told the religion students that he studied literature at the Sorbonne University in France before he became a journalist for the Israeli paper Yediot Arhronot in Dec. 1949. I have shown in Questions on Elie Wiesel and the Sorbonne that that claim is false. Wiesel also told the students he cannot answer the questions: Why did the Holocaust happen? and Why did it happen to the Jews? But … “since I have survived, I feel I have a duty to do something with myself.”

In all their discussions of ethics, the pressing current persecution and torture of the Palestinians by Israel is never brought up. EWCTW will continue to report to you about Wiesel’s activities at Chapman. Contributions sent by readers are welcome.

* * *

Also see: Beyond Sensationalism: Writer Discusses Holocaust Literature. Ruth Franklin is on the book circuit trying to explain why holocaust memoirs are so full of fiction.

“From the very moment, it is imagination at work,” explained the writer. “There’s this myth that Holocaust texts emerged fully-formed from their creators. However, so much rewriting was done to tell the story in a more effective, memorable way.” Uh huh. sure.

Elie Wiesel and the Mossad, Part IV

Written on March 22, 2011 at 10:45 am, by Carolyn

By Carolyn Yeager

copyright 2011 carolyn yeager

Déjà vu. Elie Wiesel becomes an American but his ties to Israel and manner of life don’t change.

Arriving in New York in 1956, Wiesel is greeted and assisted by “Israeli colleagues” who accompanied him and “served as real-estate advisors.”14 Everywhere Wiesel goes there are Israelis on hand to help; he is never alone or “on his own” and we must conclude that he never has been. Some of his named associates at the time are David Gedailovitch, a.k.a. David Guy, a perfume merchant and restaurateur; Jacob Baal-Teshuva, an Israeli Film weekly rep; Richard Yaffe, correspondent for an Israeli daily who had been subpoenaed by the House Committee on Un-American Activities. Wiesel hangs out with Jews, of which there were no lack in New York, and seems only comfortable with members of his own Tribe—even more so if they are fellow Zionists, which most seem to be. The French Catholic François Mauriac appears as the sole exception, but that relationship existed purely for career advancement.

Wiesel says he loved covering the United Nations, where he spoke most often with Abba Eban, Israel’s “young ambassador.” [Rivers, p 290] But, as he always does, he tells us that he wasn’t paid a living wage and had to “alleviate [his] financial problems” with free-lance work. Also, as so often happens, an unnamed benefactor shows up–an “editor” who told him he had no money for news reports, but did have a budget for a novel. Wiesel replied, “I may have something stuck in a drawer somewhere.”

Wiesel writes his first novel

I sat at the typewriter that very night, and in a week or two I churned out (under the pseudonym Elisha Carmeli) a romantic spy novel of which I remember only the premise: A man and a woman, both Israeli intelligence agents, are desperately in love, and one or the other is sent on a mission to Egypt. I can’t recall if the operation was a success, but I do know that all my characters died at the end, since I wasn’t sure what else to do with them. [p. 291]

Déjà vu, indeed. Under pressure, Wiesel churns out in “a week or two”—just as he did on the ocean liner to Brazil less than two years previous15—a spy novel? In this instance, we have to assume he was still working at his regular job, so the fact that it was a shorter book should not be held against him. But, here are my questions: How does he explain that as a religious, idealistic young man, he knew how to weave together a believable story about Israeli spies? Why did he even choose the subject of spies, rather than a simple romance between displaced persons, or immigrants to Israel—something he had seen close up, and even experienced? I know enough about writing to know that when one has to write something in a hurry, one will always choose the most familiar theme. Otherwise too much research is required; without it, mistakes will certainly occur.

Though this is a small detail tucked into Wiesel’s memoir, I think it speaks volumes about that with which Wiesel was actually familiar.

The “editor” published the book under the title, Silent Heroes.16. Wiesel says he never read the book, but Simon Weber, news editor of the Jewish Daily Forward, noticed it and, based on it, offered Wiesel a job with his newspaper. Wiesel describes the Forward as “the world’s biggest, richest, and most widely read Yiddish daily.” [p. 291] It must have been some book! Weber didn’t hire Wiesel because of his great journalism, but because of a silly spy novel, quickly thrown together. This makes no sense except as another typical Wieselism. Wiesel obviously had connections and assistance at high levels, but he wants us to believe in the holocaust victims’ luck and miracles. Or maybe it’s that he is himself so immersed in lies that he’s incapable of telling the truth about anything. In that regard, we now come to the Big One.

Wiesel gets hit by a taxi and flies through the air to land a full block away

On a summer evening in 1956, Wiesel was crossing Seventh Avenue at Forty-fifth Street with a woman from his office when he was hit by a taxi.

The impact hurled me through the air like a figure in a Chagall painting, all the way to Forty-fourth Street, where I lay for twenty minutes until an ambulance came to take me to the hospital. […] My entire left side had been shattered. A ten-hour operation was required to reconstruct it, leaving me in a cast from neck to foot. […] One morning I was visited by a lawyer who said he represented an insurance company. He had a proposition for me: If I signed a certain document, a simple piece of paper, he would hand me a quarter of a million dollars on the spot. […] I was ready to sign that document and any others in his bulging briefcase. But my journalist friend Alexander Zauber screamed, “Are you crazy? Don’t sign anything!” […] You really want to let this crook ruin us? Tell him to get the hell out of here! I’ll get you a lawyer who defends victims instead of swindling them. You’re going to be a millionaire, I guarantee it!” [p.293-95]

Zauber showed the insurance emissary to the door. But Wiesel was worried about paying his current bills, mostly because he was about to be moved into a double room, for him “a terrifying prospect. Ever since the war the idea of sleeping in the same room with a stranger had panicked me.” With the immediate insurance money, he could remain in a private room. Therefore, he decided to call the insurance agent back that night, after Zauber had gone. [p.296]. But again, help arrived from the Irgun …

I had forgotten to allow for the possibility of a miracle. Among my visitors that day was Hillel Kook, who asked Aviva and other friends to leave us alone. He was an unusual man, the archetypal Central European intellectual in demeanor and looks; nearsighted, thin, tense, and curious. I had interviewed him several weeks earlier. He had just founded a political organization to combat Soviet interference in the Middle East. I knew him by reputation only. A member of the Irgun high command under the alias Peter Bergson, he and the writer Ben Hecht had directed the Committee of Hebrew National Liberation during the war. Their main objective was to save European Jews. In fact, no one had done more than Bergson to alert the American public to the tragedy of the Jews under the Nazis. Consequently, he was thoroughly disliked by the American Jewish establishment, which consistently fought and slandered him. During the Altalena affair he was even imprisoned by Ben-Gurion. “I heard what happened to you,” he said, coming straight to the point. “As you’ve probably discovered by now, being sick in New York costs money. You don’t have any, but I do. So I brought you a few blank checks. Fill them out as the need arises, and let me know when you need more.” Hillel’s manner was matter-of-fact, as though he made gestures like this every day. [p.296]

Right: Hillel Kook, a.k.a. “Peter Bergson,” member of the Irgun High Command was another of Wiesel’s Angels of Mercy. He worked in America as an undercover agent, then made a considerable fortune on Wall Street in the 1950s and 60s. 17

I was so overcome by his generosity that I was unable to utter a word. I gaped at him as though he were a tzaddik or an emissary of the Prophet Elijah, most unpredictable of prophets. Finally I managed to ask him how I would ever repay him. “Don’t worry,” he replied, as nonchalant as a banker addressing a colleague. “I have plenty to live on. You can pay me back when the insurance company pays you off.”

When Aviva and the others came back in, I told them of the miracle. Zauber cried, “It’s a sign from God. He wants you to listen to me. Don’t be a fool. Now you can stay in your own room and you can hire my lawyer.” “You’re going to be a millionaire,” he said. “My friend the millionaire. I warn you, if you sabotage my plans, I’ll kill you. And my lawyer will defend me.”

Every week, Hillel called to find out if I needed more checks. In the meantime, the lawyer filed the suit that he and Zauber assured me would change my life for good. I made statements, signed documents and depositions. A month, a year went by. I returned to my hotel. Zauber returned to Israel, Bea to Montreal. From time to time I asked the lawyer how things were going. He was a patient man, and he advised me to follow his example. Eighteen months after the accident he accompanied me to court. This was not yet the trial, but a simple procedural matter. Two years after the accident, there was still nothing. One day Hillel called me, and we had coffee together. He asked me about the trial. Wall Street, it seems, had not been kind to him, and he was short of cash. But not to worry, he would work it out. He would wait. That day I instructed my lawyer to settle the matter within the week. He tried to talk me out of it. […] The next day he informed me of the result of his negotiations: He would receive 30 percent of my payment and from the rest Hillel would be paid back.

That’s how I failed to become a millionaire. [p. 297]

The prodigal visits his hometown Sighet

In 1960, Wiesel’s book Night was published in English, but was slow to catch hold. In 1961 the Adolf Eichmann trial in Jerusalem was the object of his attention and journalism, which he covered for the Forward. In 1964, at the age of 35, he [or his handlers] decided the time was right for a trip to Sighet, his alleged hometown, via Budapest, Bucharest and Baia-Maire. [p. 357]

In Budapest I visited the Jewish quarter, seeing traces of its past. […] When I finally did return to Sighet, the cemetery was the first place I wanted to visit, to meditate at my grandfather’s grave. As is customary, I would have to light candles. I found a store and bought two candles. So it was that I had the feeling I was following a scenario written by someone who existed only in my imagination. Michael 18 was my precursor, my scout. I followed his every step. I saw through his eyes, felt what he felt as I wandered the streets among passersby who didn’t recognize me or even glance at me, and as I entered my home, a stranger in my own house. [p. 357-8]

Above left: Photo of the house where Elie Wiesel allegedly grew up in Sighet, Rumania. Above right: The same house in 2007 after remodeling. Is the blue and white paint in honor of Israel? His parents are said to have run a grocery store on the premises, but we can see no evidence of that in the pictures.

We should not be surprised that Wiesel again experiences his early life as if he were a character in his own fictional writing. In Night, supposedly the “true” account of his time at Auschwitz and Buchenwald [“every word is true”], he was Eliezer, the 13-year-old boy [not 15 as he was in real life] who saw flames shooting from the crematory chimney as he disembarked from the train at midnight, followed by a burning pit of fire in which babies were being thrown. Now, he becomes “Michael,” from another of his novels, as he “wanders” through Sighet. Was it so unfamiliar because he had never really lived there, just as he was never really in Auschwitz or Buchenwald?

Further, we can ask: How did he “enter his home?” Was it empty? Did he ask the current residents for permission? Those answers not being given, it remains left to our imagination.

Though it hadn’t changed, I found it hard to orient myself in the little town. It seemed not to have endured a war. The streets were teeming with people. The park was as it had been, the trees and benches still in place. Everything was there. As before. Everything except the Jews. I looked all over for them, looked for the children

[…]

I roamed the streets, stopped at the movie house, went to the hospital. No one paid attention to the prodigal returning home from afar. It was not only as though I didn’t exist, but as though I had never existed. Had there really been a time when Jews lived here? 19 [p.358]

[…]

I continued my rediscovery of Sighet. Walking down the Street of Jews—almost every town in Eastern Europe had one—I saw nothing but sealed shutters and doors nailed closed. All […] now stood empty. It struck me how poor they had been, those Jews of Sighet so dear to me. That was true of all of us, though as a child I had been unaware of the poverty that prevailed in the Jewish neighborhoods. 20

[…]

I set out to see the synagogues again. Most were closed. In one I found hundreds of holy books covered with dust. The authorities had taken them from abandoned homes and stored them here. In a frenzy, I began to look through them. I was rewarded when I discovered a few that had belonged to me. I even found some yellowed, withered sheets of paper in a book of Bible 21 commentaries: a commentary on the commentaries I had written at the age of thirteen or fourteen. The handwriting was clumsy, the thoughts confused. [p.359-60]

Which “authorities” is he referring to: Jewish or Hungarian? Would the Hungarian police have bothered to take books out of the homes and store them? And what are the odds that he could look through “hundreds of books” in the time he had and find some of his own in the piles? Or that his would be stored at one of the few still-open synagogues in Sighet and his commentaries were still in them? He falls back on his previously used artifice that it was possible because he did it “in a frenzy.” As he typed 862 pages of a difficult manuscript in two weeks max in 1954—in a frenzy, so now he does another impossible task in a frenzy. Further, has anyone ever seen these handwritten commentaries? Would he have left them there? They would offer proof that he actually lived in that town.

Previously I wrote about the question of Wiesel’s typing ability. He has written that he sometimes went as a youth to the synagogue ‘office’ where he used the only typewriter available in the community to type up his religious commentaries. But now he writes that those he found were handwritten. He has also made it clear that all his adult writing has been done in longhand, not typewritten. This is unusual for someone with a long career as a journalist.

A mission to bring Soviet Jews to Israel

In 1965, Wiesel made an “unexpected journey to the Soviet Union.” It may have been unexpected because the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs requested that he go, but he was carefully prepared for it.

Meir Rosenne and Ephraim Tari, two of the most effective and devoted young diplomats in the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs, prepared me. Both spoke French, were interested in literature, and, as it turned out, belonged to a semiofficial government office reporting directly to the prime minister. Meir in New York and Ephraim in Paris oversaw clandestine activities on behalf of Soviet Jews. It was an arduous task, more dangerous than it appeared. Arduous because even the largest and most influential Jewish communities refused to become actively involved. They were delighted to aid Israel, but the desperate Jews behind the Iron Curtain were both distant and invisible. Nobody seemed to know what concrete action Soviet Jews really wanted Jews in the West to take for them. [p.365]

[…]

How many were they? There was talk of millions, but that figure seemed implausibly high. “You ought to go and see,” both Israelis told me. “You have been a witness before, now you must go and find out the Soviet Jews’ true situation and testify for them.” […] I was briefed by experts. [p.366]

Why was Wiesel the choice of the Israelis who reported directly to the prime minister about clandestine activities regarding Jews in the Soviet Union? Was he famous in 1965? Was he the High Priest of the Holocaust at that time? No, that was still to come. But he was a Mossad agent, and on their payroll, at least as a retainer. Wiesel seems up to now to have been involved when immigration of Jews to Israel—legal or illegal—was concerned, and to bolster the feelings of Jewishness of those in the diaspora. This trip appears to follow in that vein. Communist Jews were perfectly acceptable, as dark-skinned Morrocan and Ethiopian Jews were earlier. The idea was to fill up Israel with Jews in order to keep claiming more of the physical territory of Palestine.

I left for Moscow in time for the High Holidays, then went on to Leningrad, Kiev, and Tbilisi. I returned transformed […] I immediately felt close to these forgotten, tenacious Jews. … Having survived the massacres of the Nazi era and the Stalinist persecutions, they proclaimed their Jewishness even in the heart of the Gulag and the cellars of the NKVD and KGB. [p.366]

[…]

We were determined to help the Jews left behind the Iron Curtain, even if we had to defy the Kremlin and all its police. We had been privileged to make the surprising discovery that with a number of notorious exceptions, even Communist Jews had remained Jewish. [p.369]

Notice the “we.” He was working with others on behalf of Zionism and its goals, not on his own. Wiesel can find good things to say about all Jews, no matter how much blood is on their hands—for example, Zinoviev and Ehrenburg.

Left: Grigory Zinoviev, a.k.a. Apfelbaum, born Radomysisky in Russia, died 1936, was a close associate of Lenin. Right: Ilya Ehrenburg, a leader of the hate campaign against Germans during WWII, author of the article “Kill” which appeared in 1942. His support for Stalin never wavered.

A journalist friend told me that Zinoviev—Lenin’s companion and ill-fated admirer/adversary of Stalin—faced execution with the Shma Yisrael on his lips. All his life he had clung to his atheism. For a Jew to be a Communist meant repudiating his or her Jewish faith, Jewish tradition, Jewish history.22 And so many became resigned to integration, assimilation, and mixed marriages—anything to ensure that their children would no longer be tied to the Jewish people or to Jewish destiny. And yet …

Ilya Ehrenburg was an example. During the last years of the war, along with Vasily Grossman (author of the brilliant Life and Fate), he scoured cities and villages, gathering chronicles and testimony from survivors of the ghettos and the camps. Together they compiled an anthology of human cruelty and Jewish suffering reaching from Vilna to Minsk, Berdichev to Kiev, Kharkov to Odessa. This “black book” contained accounts one cannot read without feeling despair. It was not published because by 1945 Stalin had changed his policy toward both Germany and the Jews. The Kremlin’s spokesmen and propagandists received orders to no longer emphasize German atrocities or the calvary of their Jewish victims. […] It was he [Ehrenburg] who had entrusted a copy of the manuscript to a reliable friend who was to convey it to Jerusalem when the chance arose. Novelist, pamphleteer, propagandist, and Communist, if not Stalinist, Ehrenburg nevertheless had remained a Jew at heart. [p.369]

Ehrenburg, the murderer of millions of Russians and Germans, is hailed as a True Jew by Elie Wiesel! This is the true Wiesel, who will forgive any Jew as long as he professes himself a Jew and proves loyal to Jewry. He celebrates this recognized monster, releasing him of all his sins because he compiled a book of Soviet lies about “Nazi atrocities” and the sufferings of Jews. Stalin changed his policy in 1945 because Germany was no longer a threat to him, but the Jews were, just as they had been to Germany before, and before that to Czarist Russia. This is a low point in Wiesel’s memoir, but he is trapped in his own ideology and complete insensitivity to any but Jews.

A second trip to the USSR

Wiesel made a second trip to the USSR about a year later. Though it was more difficult to get in since he had published about his first trip, still he and a friend, Michel Salomon, managed to return. Once again his high-level connections made it possible. At the airport,

the Israeli charge d’affaires, David Bartov, and his wife, Esther, had come to greet us. [ …] We sped through the city in David’s diplomatic vehicle. Two spacious rooms had been reserved for us at the National Hotel. That very evening the Bartovs took us to a performance by a traveling Yiddish troupe. [p.370]

Don’t they ever get away from Jews? No, they don’t appear to have any desire to. Also, note what priceless benefits statehood has brought to international Jews–they have diplomats with special privileges and immunity, and greatly improved international connections.

On this trip, Wiesel says he was followed by KGB agents, his hotel room was searched while he was out, and the copy he brought along of his newest book on the plight of Russian Jews, The Jews of Silence, was taken. Finally frightened by this, he was back at the airport for a return flight back to Paris, about to board, when …

The young woman motioned to me to board, but at the same instant the officer shouted something. Suddenly things moved quickly. Before I realized what was happening, the two Israelis were at my side. One of them took my ticket while the other snatched my passport out of the officer’s hand. I felt myself being lifted like a package. They ran, and so did I, amid whistles and shouted orders. I don’t know how we managed to jostle our way through all the gates and barriers, but we jumped into the embassy car and took off. Why the police didn’t stop us, I don’t know. I was too stunned to try to understand, too dazed to think about it. The Israeli behind the wheel drove as if he were back home in Tel Aviv. I would worry about that later. In a moment we were on embassy grounds. [p.374]

Wiesel tells about this trip in great detail, taking five pages, which means it probably happened the way he says. Why can he do it in this instance, while other, more important events in his life are sloughed over in a single paragraph? I leave the reader to answer that. After spending three days at the Israel Embassy, things were “straightened out.”

Accompanied by my two Israeli bodyguards, I returned to the airport. Everything went smoothly. The Intourist and Aeroflot employees greeted me amiably. There was no problem […] The plane was half empty. I had the whole first-class section to myself. 23

[…]

I arrived in Paris just in time for the annual conference of French Jewish intellectuals organized by Jean Halperin and Andre Neher under the auspices of the World Jewish Congress. Rather than speak on that year’s designated topic (God and …), I recounted my experiences and impressions while in Moscow. [p375-6]

Above: Elie Wiesel at a rally for Soviet Jews in New York after his two trips to the Soviet Union. Wearing dark glasses, he looks the role of the undercover agent.

A couple pages later, we gain some insight into Wiesel’s fanatical and totally Jew-centered world-view when he speaks about the Talmudist Saul Lieberman, with whom he was thrilled to be able to study.

He made me aware that to be a Jew is to place the greatest store in knowledge and loyalty; that it is because he recognizes divine justice that he speaks out against human injustice. That it is because a Jew remains attached to his God that he is permitted to question Him. It is because the prophets loved the people of Israel that they admonished them and reprimanded their kings. Everything depends on where you stand, my master used to say. With God anything can be said. Without God nothing is heard. Without God what is said is not said. [p.380]

This explains to some extent to me why they can lie so easily. All Jews are with God, therefore anything can be said. Those without God—goyim, gentiles—are not heard. What they say is not said, means nothing. This is a reasonable interpretation which we see acted out everywhere before our eyes. It makes clear why the Gentile world and the Jewish world cannot adjust to one another. All such talk by Jews that if the Gentiles would just make enough concessions it would be possible, is deceitful. At least it is when dealing with Jews like Elie Wiesel and Saul Lieberman.

The Mossad motto: By way of deception (deceit), thou shalt make war (defeat thine enemies). Elie Wiesel has been shown again and again to be deceitful. Thus, he is perfectly in tune with the Mossad.

Endnotes:

14. Elie Wiesel, Memoirs: All Rivers Run to the Sea, Knopf, 1995, p. 286.

15. Wiesel claims to have written Un di Velt Hot Gesvign, a Yiddish manuscript of 862 pages, while on a boat traveling to Brazil in Spring 1954. See http://www.eliewieseltattoo.com/the-shadowy-origins-of-night

16. Silent Heroes is not ever listed among the books Wiesel authored, nor could I find it at Amazon.

17. http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2010/04/27/pen_portraits_from_a_forgotten_middle_east?page=0,4

18. Michael is the main character in his book The Town Beyond the Wall [1962], a fictional account of his life in Sighet.

19. According to one visitor: In the spring of 1944, more Jews than Gentiles lived in Maramureş, a remote part of Romania then under Hungarian control. Most had come in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries from Russia. (They are really Russians, not Hungarians or Romanians.) Some worked the farms, and some lived in villages and towns, working as traders and craftsmen. There were synagogues in most villages, and in the regional capital, Sighet, Jews worshiped at the elaborate synagogue on Nagykoz Street.

20. Yet Wiesel, or his handlers, presents his family as prosperous, progressive, cultured and upstanding. We see pictures of them looking fairly middle-class. Sighet was the capital city of the province. What is the reality?

21. By “Bible” he really means Talmud.

22. This is simply not true, but is Wiesel’s attempt to separate Jews from the Communist taint.

23. We learn from this that Wiesel travels first class. What else would we expect?

Elie Wiesel and the Mossad, Part III

Written on February 22, 2011 at 10:35 am, by Carolyn

By Carolyn Yeager

copyright 2011 carolyn yeager

Edited for the 3rd time on March. 1st, 2011

1949-1955: Wiesel’s movements and life-support system during these years follow an odd pattern.

In January 1949, six months after the establishment of Israel as a state, the purpose for the Irgun presence in Europe changed. Their Paris newspaper Zion in Kamf no longer being necessary, the office shut down. “Elie Farshtei and his lieutenants, Joseph [Wiesel’s boss] among them, were recalled to Israel. I received no orders or aid from anyone. “Why don’t you come with us?” Joseph asked. I promised to think about it.” 11

This is problematic. Was Wiesel’s enthusiasm for Israel simply in his fantasy? The formation of Israel had seemed to mean everything to him; why would he not want to live there now it had become a reality? It was also a logical solution to his stateless status. Once again, we feel we’re not given the true picture. Was Wiesel “not recalled” with the others because he was more useful in Europe, where he could better serve the new state. He says he now returned to his “studies,” and “There were days when I was so absorbed in my reading that I never left my room. I had nothing to seek in the desert.” [Rivers, p 174]. The world around him in Paris, where he supposedly preferred to stay, he calls a “desert!” Actually Israel was a desert, not Paris. Wiesel reveals his disdain for the Gentile world, even though he takes advantage of everything it offers him.

After loafing about for awhile, his sister Hilda’s brother-in-law arranged to get him a press card, which gave him certain privileges. Wiesel worked it out with the Jewish Agency—which after Israel’s independence became the mandated organization in charge of immigration and absorption of Jews from the Diaspora—to travel to Israel. They prepared a plan for him to join a group of immigrants in May or June [1949], traveling from the train station in Lyons to Haifa. He had the idea to become a foreign correspondent for an Israeli paper.

The group happened to include a few Irgun veterans but they were leaving Europe for good, and I was ashamed to admit that I was less idealistic and above all less courageous than they. My wallet was not quite empty; a few thousand francs (my life savings) plus one pound sterling, a gift from Freddo. [P 175]

Here again, he attempts to show he is on his own, and poor, with the explanation that he can, but only barely, afford the trip. When they reach Marseilles and the sea, they go to a camp filled with Jews in transit, waiting for their passage on the ship Negba. Now he and the other Jews are in a transit camp where deprivations and close quarters are taken in stride. One man whom they asked about military service in Israel said:

Sure it’s tough, but consider this: Once I was a partisan, an underground fighter hiding in the woods like a hunted animal, not daring to come out except after dark, and now I’ll proudly wear the uniform of the Israeli army. [P 179-80]

This is a, perhaps unintended, confession of a Jewish “underground fighter” who “came out after dark” to attack the regular German troops. Wiesel comments on this, revealing his conspiratorial view of the world:

I grew up in a tradition that denies chance. Though not everything is predetermined, everything is linked. Nikos Kazantzakis (a Greek Jewish author) once said, citing an Etruscan proverb: “It is not because two clouds are joined that the spark ignites; two clouds are joined so that the spark may ignite.” Yet, free will and the possibility of choice exist. Rabbi Akiba tells us that all is foreseen, though human beings have free choice. [p180]

In other words, do events happen and result in a consequence, or is a desired consequence the cause of events happening?

Elie Wiesel on the boat to Israel in 1949, at the age of 20.

In Israel, after his initial enthusiasm, and joy in walking on the holy ground, Wiesel was disappointed over the lack of acceptance among Jews. He heard complaints and recriminations … some people said they were “not accepted”—these were the camp survivors who were seen as weak by the new Israeli “natives.”

In this atmosphere little attention was paid to the Holocaust. For many years it was barely mentioned in textbooks and ignored in universities. In the early fifties, when David Ben-Gurion and his colleagues finally decided to pass the Knesset bill creating Yad Vashem, the Holocaust Memorial, the emphasis was on courage. Resistance fighters were presented as a kind of elite, while the victims—the dead and survivors alike—deserved at best compassion and pity. The subject was considered embarrassing. [p 184]

[It’s true the “Holocaust” was built up over time. Interest in it was fanned, beginning with the Adolf Eichmann show trial in 1961-62 and increasingly in the seventies, by the media and Hollywood. Elie Wiesel played a major role in establishing memorial museums, especially in Washington, DC , funded by U.S. taxpayers, playing on his theme of “Memory” with the help of influential newspapers with wide readership like the New York Times.]

Wiesel now says it was in Israel he got the idea to become a foreign correspondent. He writes that he got a recommendation to the editor of the small Yedioth Ahronoth newspaper, a Dr. Herzl Rosenblum, 12 a signatory of Israel’s Declaration of Independence as a representative of Jabotinsky’s Revisionist Zionist Irgun movement. Upon being hired by Rosenblum as the paper’s “foreign correspondent,” Wiesel sailed back to Paris on the Kedma, arriving in January 1950. [p 185]

I had lost track of Shushani 13 and François, but decided it would be a mistake to interrupt my studies on that account. I made a promise to myself. I vowed I would never spend less than an hour a day studying. [p 187]

Once again, it’s clear that, to Wiesel, “studying” meant reading on his own, not attending classes. Always needing to explain how he lived, he writes, “Money remained the problem. Once again, Shlomo Friedrich, my angel of mercy, managed to steer some free-lance translations and editorial work my way.” [p 188] We will see more of this type of explanation. Whenever Wiesel needs to solve the mystery of the appearance of needed cash, “free-lance” work is often the way he does it. Something to think about: Why Wiesel did not stay in Israel, among his own people who were so friendly and helpful, rather than choose to struggle in Paris as a stateless person? The most obvious answer is that he was assigned a job to do in France for the benefit of Israel. “I worked in my hotel room, a sunless cubicle overlooking the courtyard,” he writes.

In 1950, Elie Wiesel’s opportunities for travel begin … with a little help from friends

Suddenly wanting to return to Israel to talk to his new editor [or handler?] face to face, he somehow manages an appointment with a director of Zim Shipping.

I went to see a man called Loinger … a director of Zim, the Israeli shipping company. I explained … I had to go to Tel Aviv … Loinger understood immediately [!] … he picked up the phone and issued instructions …I was to be given a round-trip ticket on the Kedma that very day.[…] This crossing was very different from the last one. I had a comfortable cabin larger than my hotel room, a private shower, fruit and flowers on the table. [p 190]

This special treatment remains unexplained. Wiesel only tells us that, once in Israel, he visited with Dr. Rosenblum and became friends with his son, Dov. No discussion about his job is reported. Upon his return to Paris, “by chance” … by chance, mind you … he meets an official of the Jewish Agency who invites him on an automobile trip to Morocco. He “quickly” got an exit visa and a transit visa, “luckily” having enough photos on hand.

But what about money? I had one month’s rent on my room saved up. I took the money, stuffed everything I owned into an old valise, and that was that. There were three of us in the car. The first stop was Marseilles, where we stayed in the transit camp near Bandol. […] Now it was Moroccans who were waiting to “ascend” to Israel. [p193]

This is the same camp he was in before. Wiesel says he questioned the Moroccans, spoke to them in fluent Hebrew of how wonderful Israel was. This little speech was enough to bring him a large tip from the camp director.

The camp director was so pleased with my little speeches that he insisted on paying me ten thousand francs (two hundred dollars). At first I refused, but I finally said thank you and put the money in my pocket. We set out for the Spanish border, I was terrified of the police and customs officials who examined my stateless person’s travel permit. Would they take me for a Communist agent, a veteran of the International Brigades? True, I could tell them I was only eight to ten years old during their filthy civil war, but did fascists know how to count?

Ouch. What to say about this? First, $200 in 1950 was the equivalent of around $1000 today. Could a camp director hand out that kind of money to a stranger for relating some feel-good stories to his transient charges? Not unless he was rich and very generous. We can only believe this story as told if we understand the camp as part of the Jewish Agency network for assisting immigration into Israel, and the “director” as something more than just a camp director. More likely, he was quite aware of journalist Wiesel, and what his needs were. Secondly, Wiesel’s extreme bitterness toward the “fascist” Catholic-Franco Spanish state is apparent here. He knows he is not dealing with Jew-friendly power and is nervous without that support. But he had no trouble and the threesome made it into Morocco.

I was dazzled by the subterranean nightlife of Tangier, a cosmopolitan city of countless entrepreneurs, from the most honest to the shadiest. [p196 – Now this is a Jew-friendly place.] … We crossed Spanish Morocco at breakneck speed and, arriving in Casablanca, encountered a blinding but somehow soothing whiteness … My traveling companions had contacts within the Jewish community. [p 197]

I bet they did. A poorly dressed Jew offered to serve Wiesel as a guide; he proved to know his way around the Jewish community, introducing Wiesel to many and varied sorts of people . One Saturday afternoon they attended a meeting at a Zionist club. Wiesel writes that after “teaching a few songs” to the local members, his traveling companion from the Jewish Agency gave him an envelope containing money that seemed “princely to me,” assuring that there were “no more money worries for two or three weeks.” [p 198]

Wiesel says he wrote articles while there, without really understanding the culture. When he returned to France, he received a telegram from ‘Ifergan,’ his guide: “Your articles aroused anger. I am now in the hospital, with a few broken ribs.” Twenty years later, Wiesel wrote in Yedioth Aronoth about this “wrong” he had inadvertently caused, and received a response from ‘Ifergan’ that contained the following:

Don’t blame yourself. I was only doing my job when I followed you. I was working for the Mossad at the time, and they told me to keep an eye on you. The chance of having my ribs broken was part of the deal.” [p 199]

Why would the Mossad want to keep an eye on our young journalist? What other reason could there be than for his protection. Did the unnamed official from the Jewish Agency invite Wiesel to come along because of his gift for telling stories in impeccable Hebrew and teaching songs to emigrating Moroccan Jews? That seems too simplistic. In any case, Wiesel is definitely a precious commodity who is never left without funds.

Now … twenty pages later, though dates are not given, Wiesel reports feeling “disillusioned with Europe” and decides to travel to India. Prior to this, he was passionately involved with the negotiations on reparations with the Konrad Adenauer government. Heading for Bonn, Germany from France, he first spent a day at Dachau, where he says he was “troubled and depressed, for the Jewishness of the victims was barely mentioned.” [p 202] He is no doubt unaware to this day that few Jews were kept at the Dachau camp. Typical Wieselism!

The Zionists offered him a well-paid job, with lodgings in a luxury hotel, as interpreter for Nahum Goldmann, the Polish founder and long-time head of the World Jewish Congress, at the conference of the WJC in Geneva. The Jews were deciding/debating the reparations issue among themselves. Wiesel says he was against the German reparation payments on the grounds they would lead to forgiveness or a “balancing of the shoah account.” Those in favor, such as Goldmann, argued the money for Israel was most important, while those against, including Wiesel’s former Irgun leader Menachem Begin, felt they stood on the moral high ground and would lose it by accepting financial compensation, which signaled “forgiveness.” Wiesel has always been against forgiveness. Goldmann has always been for the money, and “the Holocaust” was just another way to get it.

Left: Russian-born Nahum Goldmann, the long-time head of the World Jewish Congress, in 1966. Below: Moshe Sharett and Nahum Goldman, 3rd and 4th seated from left, signing the German-Israel Reparations Agreement in Sept. 1952

Miracles, miracles …Wiesel makes his most miraculous trip of all—a journey to India.

I had long dreamed of visiting India, drawn to it by a desire to meet not maharajahs but sages, yogis, and ascetics … why not compare the Jewish idea of redemption with the Hindu concept of nirvana?

Travel expenses were a problem. Yedioth had no money, so I didn’t even bother asking. I wrote ten articles for various Yiddish newspapers, promised ten more for later, did a few translations, and bought a lottery ticket for the first time in my life. Miracles of miracles, I won a modest amount, and at last I had a ticket in hand, but not much more. The two hundred dollars in my wallet would not take me far. [p 223]

Lottery ticket? Isn’t that the lazy Wiesel mind again, coming up with whatever explanation comes to him without bothering whether it’s believable or not? My interpretation is that he is so confident of being protected by varying sorts of ubiquitous “Mossad agents,” even those of a volunteer status, that he doesn’t need to worry. Or is he just having fun with us? At any rate, we have here the usual nonsense. He wrote “ten articles” [nice round figure] for “various” newspapers” and promised ten more [for a cash advance?]. I ask: If he could get this work whenever he needed it, why not do it all the time and end the relative poverty he claims he was living in? Also, note the $200 figure again. This is not the last time we’ll see it.

There remained the question of a visa. Dan Avni, press attaché of the Israeli embassy … phoned his Indian colleague and settled that matter for me.

What Indian colleague is he speaking of? India didn’t establish diplomatic relations with Israel until 1992. At any rate, there was an “Indian colleague” who arranged an entry visa for Wiesel. Do you think he also got some assistance while he was there? But he never mentions anything like this; he pretends he was just helped along by miracles. It’s pretty clear, however, that he had to have some kind of unofficial business to carry out for Israel. With diplomats easing his way, he was off.

During the crossing—with stopovers in Suez and Aden—I studied English, read […] A fellow passenger […] gave me the name of an inexpensive hotel in Bombay. [p 224]

The passenger was a “medical student” who also played the ponies. He convinced Wiesel to wager some of his $200. This doesn’t sound like something Wiesel would do, but he says he did and came out even. The passenger, however, lost his money and now convinced Wiesel to lend him his $200 [to bet more!] until they reached Bombay, where he would be able to pay Wiesel back. And Wiesel did so! When they disembarked at Bombay, a very worried Wiesel searched the crowd for his “friend” and, lo and behold, he showed up with the money in hand. This is a strange story. It sounds like the yarn of an inveterate story-teller, embellishing greatly on something that in reality was far less suspenseful. At any rate, it’s definitely not one of prudence; and may be told to demonstrate his uncanny “luck.”

Wiesel wanders around Bombay, encountering begging children and orphans. He “set out in search of the country,” but reveals no plan of any kind to his readers. How far would he get on $200/$1000? Well, naturally, a miracle intervenes.

One day I met a rich and influential Parsi. (Seemingly sitting at an outdoor café.) We chatted about this and that, and he found something about me intriguing. (His Irgun handshake?) […] Several hours later, as he left to return to his associates, he gave me a calling card on which he had written a few words. “India is a vast country, he said. “You will undoubtedly move around a lot. With this card you can take any domestic flight to any destination.” I didn’t know how to thank him. In fact, it took only a few weeks for me to appreciate the true value of his gift. Whenever I was hungry, I would get on a plane. By then I had discovered the identity of my benefactor: He owned the airline. [p 226]

How similar this is to his experience with the Zim Shipping Lines! Wiesel throws out these stories in his 1995 memoir with little concern for how flimsy they are. He is used to people believing him and not asking bothersome questions. Again, we’re not given the name of this “Parsi” or his airline – just as we find in the concentration camp stories by Wiesel, and by many others.

I ask: How practical is it to fly from one city to the next in order to eat a meal? You end up in another place. First you have to get to the airport, wait around for the flight, board and finally be served a meal. After that, de-board the plane, wait around for your return flight and another meal, land, de-board, leave the airport and return to your lodgings. By then you will be hungry again. Were airline meals worth it? This is India in the early 1950’s—a third world country. He says he did this for “a few weeks” at least. Wiesel says a lot of foolish things, and this is just one more. He obviously had sufficient money for this trip and probably free travel arrangements made by his handlers. He is lying outrageously to his readers.

We also learn very little of substance about the country and what he did. Back in Bombay, Wiesel spends a Shabbat with a wealthy Jewish family.

I went to synagogue. My hosts proudly told me of their success. The Sassoon and the Kadouris were super-rich families, veritable dynasties. But it had never occurred to anyone to discriminate against them because of their origins or their ties to Judaism. There were so many ethnic groups, languages, cultures, and traditions in this vast country that Jews did not attract special attention. […] I returned from India even more Jewish than before. [p 228-9]

There we have it—an explanation for the Jewish drive to racially and ethnically mix all nations but their own. It is so they will not attract special attention in the Diaspora with their super-wealth. Since Wiesel sees through eyes that can only admit Jewish persecution, he is often not aware of what he’s saying, and revealing, to the rest of us who see through very different eyes. This is a paragraph that should become better known.

Left: Elie Wiesel in his early 20’s, at the time of these travels.

A few more trips—why not, they’re free.

A free ticket from El Al enabled me to visit Montreal. Bea [the younger of his two older sisters] seemed happy enough; she was now working at the Israeli consulate […] I desperately wanted to ask her a question that had haunted me for years. What was it like before the selection, those final moments, that last walk with Mother and Tsipouka? It was the same with Hilda. I didn’t dare. [p 229-230]

I’ve already commented on the reasons for this in Part II of this essay. Wiesel’s next trip is to Brazil, which I also discussed previously in “Shadowy Origins of Night” in relation to the writing of his ‘first book,’ the 862-page “lost” Yiddish manuscript. However, it is relevant to the Mossad question also.

It was Spring 1954. He was going on assignment for his newspaper Yedioth Ahronoth. It seems that some Jews who had recently arrived in Israel from Eastern Europe were poor and unhappy, and the Catholic Church, according to the Zionists, was taking advantage of their unhappiness to convert them to Catholicism with offers of free passage and visas to Brazil, and $200 each. [There’s that $200 for the third time! How to explain it? Wiesel is stuck on this number.]

His editor wants him to “go and see what’s going on” with this “Catholic scam” in Brazil. His poet friend Nicholas, an Israeli citizen, would go with him. But once again he needs to explain the money. As usual, “A resourceful Israeli friend somehow managed to come up with free boat tickets for us.” [p238] Oh, those Israelis are incredibly resourceful! Wiesel remained in Brazil for two months, but he doesn’t tell us what he did there besides writing about the Jew-Catholic “scandal” and visiting people, including relatives. When he was called back to Paris to cover Pierre Mendes-France’s accession to power for his Israeli newspaper, it was mid-June 1954.

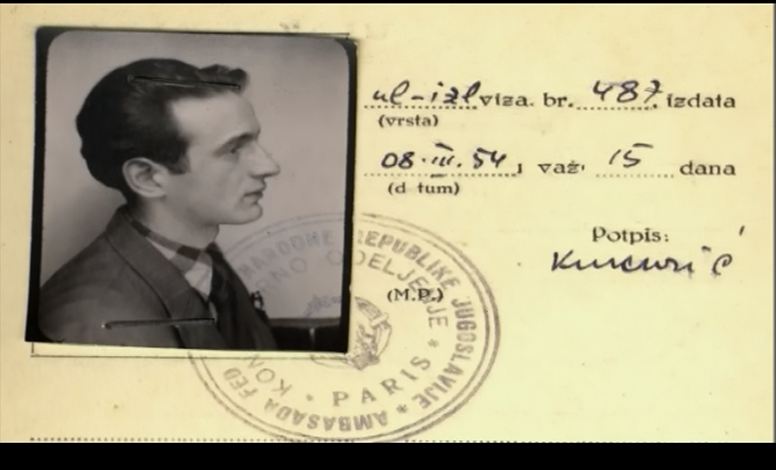

Document with Wiesel’s picture attached, dated (August?) 1954, issued by the Yugoslavian embassy in Paris . “Potpis” is Serbo-Croatian for “signature.” There is no mention of travel to Yugoslavia during this time, or any time, in Wiesel’s memoir. He appears thinner and more fragile-looking than in earlier photos when he was younger.

Document with Wiesel’s picture attached, dated (August?) 1954, issued by the Yugoslavian embassy in Paris . “Potpis” is Serbo-Croatian for “signature.” There is no mention of travel to Yugoslavia during this time, or any time, in Wiesel’s memoir. He appears thinner and more fragile-looking than in earlier photos when he was younger.

In July 1955, Wiesel makes another trip to Israel for the reason of “feeling once again the need for a change of scene.” [p 273] He went by sea and spent several weeks “making many trips through the country.” At Bnei Brak he visited the Rebbe of Wizhnitz, of his own Hasidic sect, to whom he made his famous statement that “certain things are true though they didn’t happen, while others are not, even if they did.” [p 275] That did not win him the Rebbe’s blessing.

At the end of his several-weeks stay in Israel, his editor Dov [the old man’s son] “proposed that I leave Paris and go to New York, not just to write a few articles, but as a permanent correspondent.” [p 276] Their conversation about this important decision is short and rather silly, same as with every other major event or life change that Wiesel writes about. We can easily conjecture that his Irgun/Mossad handlers thought there was now more value to be mined in New York than from his base in Paris. The German reparation talks were over, the amounts established; from now on, America was where the action was.

Next: Part IV – Déjà vu. Wiesel’s adventures in America follow the same, now-established pattern.

Endnotes:

11. Elie Wiesel, All Rivers Run to the Sea, A. Knopf, 1995, p174. [All following page numbers refer to this book]

12. Born in Kaunas in the Russian Empire (today in Lithuania), Rosenblum moved to Vienna after experiencing anti-Semitism and being prevented from studying law. In Vienna, he studied law and economics, gaining a PhD. He then moved to London, where he worked as an aide to Ze’ev Jabotinsky, a leader of the Revisionist Zionism movement. In 1935 he immigrated to Mandate Palestine and started working for the HaBoer newspaper, where he wrote under the pseudonym Herzl Vardi. In 1949, Rosenblum became editor of Yedioth Ahronoth. He remained as editor until 1986, during which time the paper became the largest selling in the country. His son, Moshe [called Dov], was later employed as editor.

13. In 1952 Chouchani left France for Israel where he remained until 1956, according to Wikipedia. See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monsieur_Chouchani

On Mirrors and Memories

Written on February 19, 2011 at 11:00 pm, by Carolyn

Elie Wiesel asks: What came first—the event or the memory of the event?

When it comes to the Egyptian “revolution” or any other current topic he is asked about, Elie Wiesel reverts to the one idea animating his life: the power of memory.

When it comes to the Egyptian “revolution” or any other current topic he is asked about, Elie Wiesel reverts to the one idea animating his life: the power of memory.

“Bearing witness is a huge commitment; it has almost nothing to do with machines. It is the eye that sees, the ear that listens.” Thus he responded to someone calling from the International Herald Tribune for comments about Egypt

The 82-year-old said, “Because of technology, and because of the progress made in technology, especially in the field of communication, no one has any excuse anymore to say, ‘I don’t know; I didn’t know; I wasn’t aware.”

Speaking of the real-time availability of news today: “Since they come from a variety of sources, from a variety of people, representing all ideologies and all sensitivities, we know. We cannot not know,” Mr. Wiesel said. “Whether you want it or not,” he added a moment later, “we are witnesses.”

Wiesel fears that, “In one way, what worries me is that there is so much chatter that we forget how to listen. Everybody has something to say. Before speaking, there is thinking. But today everything goes so fast, so fast.”

What the chatter should be asking of Egypt, he said, is: “What does it mean? Why did this happen now? Why didn’t this happen before? And not who is wrong, because we have to listen to both sides. But the main thing is, What does it mean in history, to history?”

The Internet can serve as a repository of testimony; but it can also be a palace of fun house mirrors, in which events are reflected and twisted and spun even before they have ended.

“There is no life without memory,” Mr. Wiesel said. “But when it’s too much, when it’s too much, then we no longer know, really, what came first, the event or the memory of the event.”

* * * *

Finally, an interesting idea. Just how tricky can memory be? Can we remember something before it happens? Or that didn’t happen? Elie Wiesel seems to think so. And he should know, because he’s done it. Yes, the Master of Memory says: When it’s too much, too much, then we might find ourselves in a “fun house of memories,” twisting and spinning, and getting just plain confused. It can happen. ~cy

If you’re sure you want to, you can read the original article at http://www.nytimes.com/2011/02/12/world/middleeast/12iht-currents12.html