Blog

Gigantic Fraud Carried Out for Wiesel Nobel Prize

Written on September 12, 2011 at 10:08 am, by Carolyn

By Carolyn Yeager

Proof that the man in the famous Buchenwald photograph is NOT Elie Wiesel.

With the help of the New York Times and the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, Elie Wiesel and his backers did not shy away from criminal deceit by purposely misidentifying an unknown face in this famous photo as belonging to Elie Wiesel.

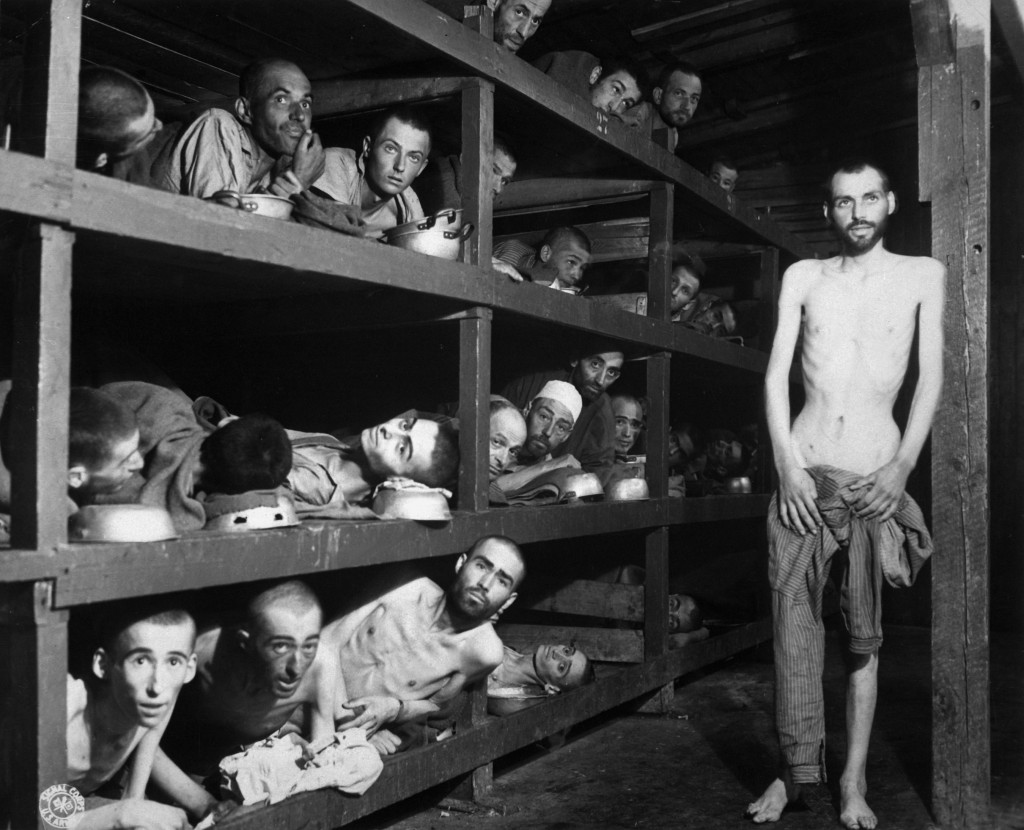

The above high-resolution photograph of Buchenwald survivors was first published in the New York Times on May 6, 1945 with the caption “Crowded Bunks in the Prison Camp at Buchenwald”. [click on image twice to enlarge fully] It was taken inside Block #56 by Private H. Miller of the Civil Affairs Branch of the U.S. Army Signal Corps on April 16, 1945, five days after the Buchenwald camp was liberated by a division of the US Third Army on April 11, 1945. None of the men in the picture were identified at that time.

The U.S. Army photographer was in block #56, not #66

The U.S. Army photographer said he was inside Block #56. The “children’s block” that housed the so-called “boys of Buchenwald” was #66. This was not a typo. Note that these men are not children or teenagers, except for the youngster on the lower left who has been correctly identified as 16 yr. old Myklos (Nikolaus) Grüner, and maybe a couple others. These adults appear to be a mixture of sick individuals suffering from a wasting disease (Grüner learned after liberation he had TB), along with basically healthy men who were also in that block, for some unknown reason, five days after they had been freed. As we have read from many Buchenwald inmates, they moved about at will from the day of liberation onward. In Elie Wiesel’s book Night, he even says that some of the boys in his block went to the city of Weimar the very next day to steal potatoes and rape girls.

The true facts of this photograph have never been told and perhaps are not known. (Grüner has written in Stolen Identity that he left a procession of youths being led to the camp entrance on the morning of April 11, scurried into the nearest barracks and jumped into an empty bunk space. It turned out to be this one.) But because of the man standing there stark naked except for a piece of clothing held in his hands to cover himself, this photograph was certainly staged. In any event, it was never represented as the “children’s barracks.” Still, Elie Wiesel inexplicably once told an interviewer for the German weekly Die Zeit that this photograph was taken in the Children’s Block and all these men were really teenagers even though they looked old. (Source: “1945 und Heute: Holocaust,” Die Zeit, April 21, 1995.)

Kenneth Waltzer wrote to this website EWCTW on Nov. 14, 2010: “Eli Wiesel was indeed the Lazar Wiesel who was admitted to Buchenwald on January 26, 1945, who was subsequently shifted to block 66…” and Waltzer repeated in another comment on June 27, 2011 that “— after his father died — Elie Wiesel was moved in early February to block 66, the kinderblock. Miklos Gruner too was in block 66. Elie Wiesel was there with other boys from Sighet, who knew him.”

But we are also to accept that on April 16 Wiesel was in block 56, even though he didn’t report any such move in his book Night. In fact, in that fictitious story, Wiesel says he became deathly ill with food poisoning three days after liberation (April 14) and spent the next two weeks in hospital (pg 115, Marion Wiesel translation). That in itself precludes his being in this photograph taken on April 16!

Whom do you believe—the New York Times or your own eyes?

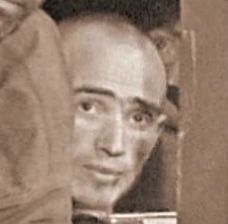

Not Wiesel at age 16 in 1945

Not Wiesel at age 16 in 1945

You can see for yourself from these two high-quality photographs supplied to me by a helpful reader that the face on the left is not Wiesel. A close inspection of the prisoners in the bunks in the famous photograph reveals that the eyebrows on many (including the one on the left above) were emphasized with a dark crayon/pencil … in other words, retouched or “photo-shopped.” On the right is what is claimed to be Elie Wiesel in 1944 at the age of 15.

The inmate on the left definitely has an aquiline nose and full, even sensual, lips. In this close-up, the receding hairline is visible on the recently shaved head. On the right, the real 15-year-old Elie Wiesel exhibits a normal youthful hairline, a bigger and longer nose and thinner lips. He also has a higher forehead and longer face than the more roundish-headed inmate. The eyes of the man on the left are not as deep-set under the eyebrows. His somewhat surprised, curious expression is not typical of Wiesel, whose expression was generally reserved, and often hooded.

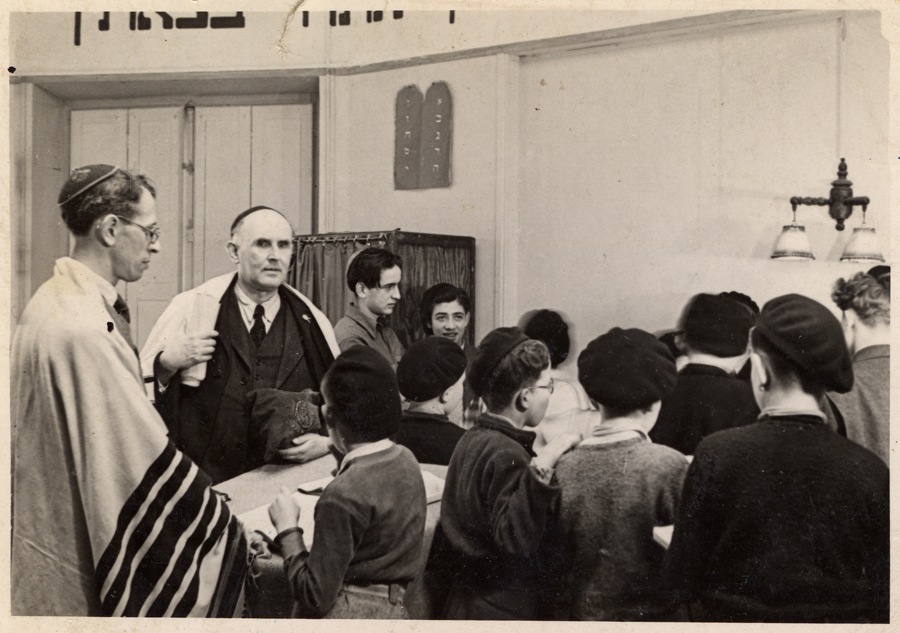

The close-up on the left appears to be the real Elie Wiesel in France later in 1945. He would be 17 or almost 17 years old in this picture. Notice the non-receding, youthful hairline with a very long front lock hanging to the side, and the straight nose .

This close-up image is from the photograph below, which is found at the USHMM Survivor Resource Center with the caption given below. (click here or on lower pic for an undistorted, larger image)

Above, Jewish boys gather for a prayer service in a chapel in an OSE children’s home in 1945. Those pictured include Elie Wiesel (seen in profile) and Jakob Rybsztajn standing next to him facing the camera. (I note that Elie Wiesel is older than the other boys in this picture, giving support to the idea that he acted in the role of counselor and sometime teacher to the newer, younger religious boys.)

Notice again the straight nose, the high forehead, deep-set eyes, large ears, sensitive mouth and slender neck. But also look at all that hair! The date of this picture is given by USHMM as 1945 and the location as Ambloy, [Loir et Cher] France. It says in the accompanying text “In October 1945 the children and staff of Ambloy were relocated to the Chateau de Vaucelles in Taverny (Val d’Oise).” That means this picture was taken between June and October 1945. They could have been celebrating Rosh Hashana, Yom Kippur or Sukkot.

But could his hair have grown to such a length from a shaved head in April 1945? No way, and thus we have another proof that the liberated Buchenwald inmate with the shaved head is NOT Elie Wiesel.

A PDF from my valued contributer examines the ages of the small group more closely. In my opinion, he has the ages of all four men a little too young but especially #2 and 4. Take a look: four men in bunk

Who first identified Elie Wiesel in the famous Buchenwald liberation photo?

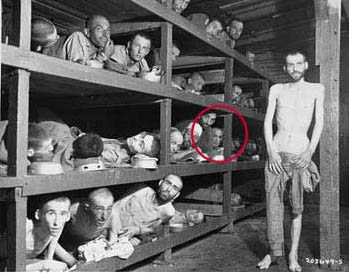

In October 1983 the Jewish-owned New York Times published this photograph as part of an article in its high circulation Sunday NYT Magazine with the caption: “On April 11, 1945, American troops liberated the concentration camp’s survivors, including Elie, who later identified himself as the man circled in the photo.”

It was also in 1983 that Wiesel’s friend Sigmund Strochlitz began campaigning for a Nobel prize for Wiesel. Letters of nomination are due into the Nobel committee by Feb.1 of each year, so by January 1984, the committee was receiving letters nominating Wiesel from U.S. Senators such as Daniel Moynihan and Barry Goldwater (both Jewish). [see “How Elie Wiesel Got the Nobel Peace Prize“] The effort continued, with new and ever more innovative ideas, through 1985 and 1986 with the help of Jew John Silber, President of Boston University, Wiesel’s employer. Hundreds were enlisted into the effort.

The 1983 article in the New York Times that was the opening gun of the campaign was written by Jew Samuel Freedman and titled “Bearing Witness: The Life and Work of Elie Wiesel.” It included this line: “His name has been frequently mentioned as a possible recipient of a Nobel Prize, for either peace or literature.” Well, it had just begun to be mentioned … by this team of cheerleaders.

Wiesel pretends that he had nothing to do with it. In an interview in France in 2009, he said: “If you fight or if you do scientific research to get the Nobel, you never succeed and you should not succeed.” (Elie Wiesel, “messager de la memoire”) No, he did not fight but his mercenaries fought for him, and he used this photograph as his “research.” That this photograph played a large role is shown by the fact that immediately after the Nobel award ceremony in December 1986, Wiesel went to Yad Vashem Memorial in Jerusalem and posed in front of its prominent display there.

After the award was announced by the Nobel Committee, the New York Times published on Nov. 1 a severely cropped version of the Buchenwald photo (below) with the caption: “Elie Wiesel, the winner of the Nobel Peace Prize (at far right in the top bunk) in the Buchenwald concentration camp in April 1945, when the camp was liberated by American troops.” The picture accompanied an article by Jew Martin Susskind titled, “A Voice from Bonn: History Cannot Be Shrugged Off.”

The role played by the tax-payer funded United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Elie Wiesel finagled his way to becoming Founding Chairman of the United States Holocaust Memorial Council in 1980 after being chosen in 1978 by President Jimmy Carter as chairman of the President’s Commission on the Holocaust. Why the United States needed to do anything at all about the “Holocaust” is something only the 2.5% Jewish population in this country can answer. It is to satisfy them. Wiesel continued to chair the Council until 1986, when he reached his goal of becoming a Nobel Laureate. The USHMM was undoubtedly an important institutional heavyweight that leveraged him to the Nobel.

The USHMM naturally accepted that Wiesel was in the famous photograph as soon as he and the New York Times said he was. If you think the museum staff does real research, is searching for truth and/or is engaged in scholarship of any kind, you are badly mistaken. The museum represents official power only and is invested in keeping it in Jewish hands.

This photograph is the only document tying Elie Wiesel to the Holocaust

The only document that connects Elie Wiesel to the Auschwitz-Birkenau and Buchenwald experience he claims to have—in other words, his claim to be an authentic “Holocaust survivor”—is the famous Buchenwald liberation photograph. There are no records with his name and birth date for either camp. His books do not support his presence there very well. That’s why the Wiesel promoters, who wanted to anchor their man’s claim to be the unchallenged spokesman for the world’s greatest victims—which winning a Nobel prize would surely do—decided that they could pawn that unknown face off as the face of Wiesel. This decision was made in 1983. It’s certain that Elie Wiesel took part in making it, though the pretense is kept up by all that he was aloof from the entire process.

What you must do

When you comprehend the immense power that this simple photo comparison and commentary gives us, you know that we have it in our hands to break down the Wiesel legend if this knowledge is widely circulated. If you understand this, you know what you must do. You must post this article everywhere you can, you must tell everyone about it, send it to all you know … make sure that this photo comparison moves through the Internet and finds a home in as many places as possible. And keep it up, because once is not enough. I’ve done my part, readers. Now it’s up to you.

New Evidence on Elie Wiesel at Buchenwald

Written on September 6, 2011 at 6:03 pm, by Carolyn

Edited on Sept. 8, 2011, 4:30 p.m.

By Carolyn Yeager

Another official transport list of the youths sent to France from Buchenwald in summer 1945 has come to my attention. Can it possibly be the “smoking gun” to prove that Elie Wiesel in not one of the “boys of Buchenwald?”

On June 14, I posted a blog on this site questioning “What Happened to Waltzer’s Book about the ‘boys of Buchenwald?’” Professor Ken Waltzer of Michigan State University wrote a comment to that blog in which he stated, “Elie Wiesel was there (in Block 66 at Buchenwald) with other boys from Sighet, who knew him; he was interviewed by military authorities after liberation, in order to permit departure from the camp; and he went after liberation in early June, 1945, to France, to Ecouis…. one among 425 boys who did so.”

Prof. Waltzer has for years been firm in his insistence that Elie Wiesel was on the transport to France from Buchenwald, as one of the “boys of Buchenwald,” a legend in the making. This is largely based on a document containing the name of Lazar Wiesel of Sighet, born Oct. 4, 1928, on the transport list of over 500 Jewish “orphans” from Buchenwald to Paris dated 16th July, 1945. (Note: Elie Wiesel’s official birth date is Sept. 30, 1928)

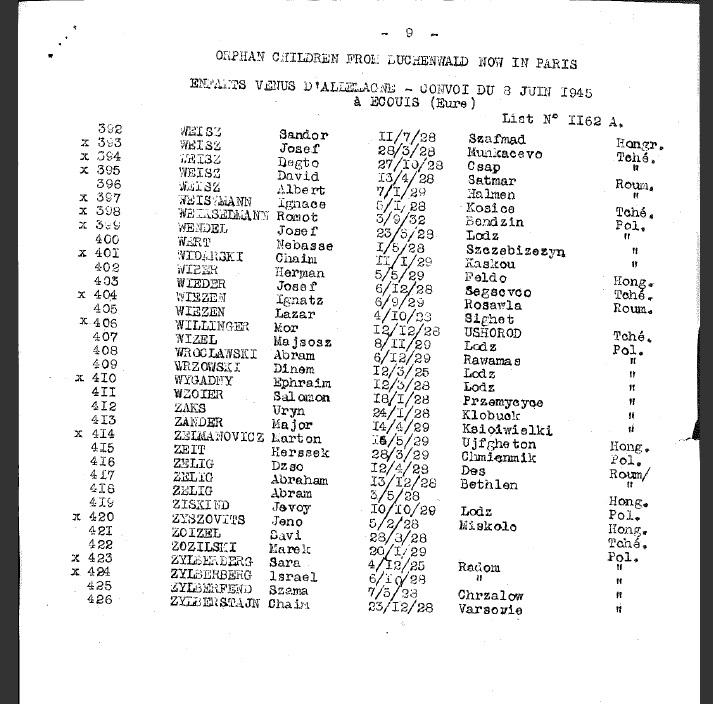

Page 9 of this list, as well as the cover page, as received by Myklos (Michael) Grüner from the Buchenwald Gedenkstätten (Archival Records Office) is viewable on Elie Wiesel Cons The World under “The Evidence” on our menu bar (click on “The Documents” and then the link at #14). You will notice on that page that number 405 is WIESEL, Lazar.

HOWEVER … it has come to my attention from a helpful, dear reader that at the website of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (http://www.jdc.org) (AJJDC) we find the same list only now it is titled “Orphan Children from Buchenwald now in Paris” –Convoy of 8th June, 1945.”

Here we see number 405 listed as WIEZEN instead of WIESEL. To get two letters in a single surname wrong seems unlikely, especially when it’s connected to a birth date that is not Elie Wiesel’s.

Wiezen or Wiesel?

That the documents are not the same is borne out by the fact that the AJJDC page 9 document above begins with #392 WEISZ, Sandor, while the Buchenwald/Grüner page 9 document begins with #398 WECHSZLMAN, Remet. In addition, there are other differences on this page in name spellings and two in birth dates.

The nature of these differences suggest to me that they may be corrections made in France to the mainly minor mistakes on the list from Buchenwald. This idea is bolstered by the probability that the AJJDC and the Jewish personnel at Ecouis had more interest in and time to spend in learning about each youth’s personal information than did the American Military personnel at Buchenwald, plus they would be more familiar with Jewish/Yiddish names and they would be more concerned with accuracy. There is good reason, when you closely compare the two documents, to speculate that the latter document was typed up in France (AJJDC version shown above) and is the more correct one.

We also have to consider how unlikely it is that the AJJDC would want to tamper with the list to change WIESEL to WIESEN, thus denying that a Wiesel was transported to France from Buchenwald. If any tampering were done, it would more likely be at the other end, at Buchenwald. But I am not charging that … yet.

Confusion over Lazar Wiesel

That said, let’s consider some other aspects. In light of the utter confusion of records for Lazar Wiesel, who arrived at Buchenwald from Auschwitz on Jan. 26, 1945 with a birth date of Sept. 4, 1913 and was given ID number 123565, but who then either got lost or was “reassigned” ID number 123165, which had belonged to Pavel Kuhn, a Slovenian Jew who arrived on the same transport from Auschwitz in January and died on March 8. (See The Documents, # 11, fig. 12.1) The name belonging to this ID number was then given as Lázár Wiesel (with accented “a’s”) who signed the Military Government questionnaire on April 22, giving his birthdate as Oct. 4, 1928 (See The Documents, #11). This is said to be the 16-year-old Lazar Wiesel coming from Buchenwald to France and arriving in Paris on June 8.

This is not at all clear! But now add to it that this person was named Wiesel when he left Buchenwald, but Wiezen after he arrived The rest of his information remains the same. Note also that the signature of “Lázár Wiesel” on the Questionaire is totally different from the signature of Elie Wiesel that is well-known. In addition, the only photograph that claims to be of Wiesel at Buchenwald is provably not Wiesel.

Everything points to an answer that Elie Wiesel was not the one who was at Buchenwald and who traveled to France in summer 1945. As I suggested in a following blog “New Photo of ElieWiesel in France?” he could have arrived in France sometime during the war—helped by the Jewish network and placed in the children’s welfare institutions there.

The ubiquity of the names Lazar and Shlomo Wiesel

I wrote briefly in The Shadowy Origins of Night, Part II that Sighet, Elie Wiesel’s birthplace, had a large Jewish population and that I had counted 19 Eliezer or Lazar Wiesel’s or Visel’s from the small Maramures District of Romania listed as Shoah victims on the Yad Vashem Central Database. Nineteen who died in the “Holocaust”! Just think how many survived and continued to carry and pass on this name. Some were no doubt relatives of Elie’s family. The same is true for Shlomo Wiesel/Vizel—there are many of them in the Yad Vashem database also.

The lesson of this, of course, is that simply seeing the name “Lazar Wiesel” doesn’t mean it is the one and only Elie Wiesel. That different birth dates are given for “Lazar Wiesel” fits this reality perfectly. It’s also true that Elie went by the name of Eliezer, his grandfather’s name, a distinction not without meaning. This will come up again, when I write about Wiesel’s family.~

How Elie Wiesel Got the Nobel Peace Prize

Written on August 18, 2011 at 7:16 pm, by Carolyn

Lightly edited on Aug. 21

Was Wiesel a strange choice?

What has Mr. Wiesel ever done for “peace” or, even more to the point, “world peace?” He was a devoted Zionist even in his youth, working as a journalist for Zion in Kampf, a Yiddish newspaper in Paris (see here). He had many contacts with the Irgun terrorist organization and cheered on their every action; he may well have been even more deeply involved with Irgun. He stated in his memoir that “I belonged to the Irgun.” He has supported every illegal military action in which Israel took over more land, homes and livelihoods of Palestinians, right up to his being an apologist for the latest unprovoked attack on Gaza in 2008-09 when the Jews used white phosphorous bombs on civilians.

Wiesel has never sought to act as a peace-maker in these ongoing unbalanced attacks, nor has he criticized or sought to stop the many wars of the United States since he became a citizen in 1963. He has also promoted a virulent anti-Germanism, e.g. “Every Jew should set aside a zone of hate – healthy, virile hate – for what the German personifies and for what persists in the German.” He has never publicly repudiated this statement.

So why was Elie Wiesel chosen for the most prestigious award in the Western world, the Nobel Prize for Peace, in 1986 when it still carried a dignified aura? (It has since lost some of that glow because so many of its recipients, including Wiesel, have lost theirs!) You’ll find the answers in the article below from The New Republic that appeared in November 1986 before the Nobel award ceremony took place on Dec. 10.

Sub-headings and photos have been added by me. -cy

Elie Wiesel gives a speech after the Nobel awarding ceremonies on December 11, 1986.

___________________

Pop Goes Elie Wiesel

How to get a Nobel prize.

by Jacob Weisberg

November 10, 1986

“I was of course very stunned and grateful, and melancholy,” Elie Wiesel told the The New York Times about his initial reaction to winning the 1986 Nobel Peace Prize. “I fell back into the mood of Yom Kippur, serious reflection about my parents and grandparents. It took me half an hour to get out of it.” But when Wiesel finally came to, he told a press conference in New York, “There are no coincidences. If it [winning the prize] happens after Yom Kippur here, then some of my friends and myself have prayed well.”

Actually, they did a little more than pray. Over the past several years, a few of Wiesel’s friends have circled the globe in an intensive effort to win him the prize. Sigmund Strochlitz (in photo below left), who owns a Ford dealership in New London, Connecticut, has directed the offensive. A survivor of Auschwitz, Strochlitz has visited the halls of Congress, the West German Bundestag, the French Assembly, and the Norwegian Parliament on Weisel’s behalf.

It might sound difficult to lobby for the Nobel Peace Prize. In reality, it’s not so tough. According to the rules of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, several categories of persons are eligible to make nominations. Parliamentary representatives, judges, academic, and former Nobel laureates are among those entitled to send letters of nomination to the committee in Oslo. They’re due by February 1. Strochlitz’s strategy has been to solicit these letters by the bushel. He’s succeeded in getting hundreds of them, including nominations from Francois Mitterand and former Peace prize winners Henry Kissinger, Lech Walesa, and Mother Theresa.

It might sound difficult to lobby for the Nobel Peace Prize. In reality, it’s not so tough. According to the rules of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, several categories of persons are eligible to make nominations. Parliamentary representatives, judges, academic, and former Nobel laureates are among those entitled to send letters of nomination to the committee in Oslo. They’re due by February 1. Strochlitz’s strategy has been to solicit these letters by the bushel. He’s succeeded in getting hundreds of them, including nominations from Francois Mitterand and former Peace prize winners Henry Kissinger, Lech Walesa, and Mother Theresa.

Wiesel’s supporters have concentrated much of their energy on the U.S. Senate. One Senate aide described their campaign as “relentless and heavy-handed.” “Strochlitz would show up every winter and say “it’s time to write letters again,” one staffer said. “He’d say, ‘you did it last year. It’s time to do it again.’ He’d get the senators to send ‘Dear Colleague’ letters to each other in an every-widening circle.” Strochlitz, a close friend of Wiesel’s, denies doing any campaigning.

Here’s how it worked. Strochlitz asked Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, for example, to nominate Wiesel, and to request similar letters from ten of his colleagues. Strochlitz provided Moynihan with the names. Of course, many of the legislators Moynihan asked had no idea they could nominate anyone for a Nobel Prize. And a few hardly knew who Elie Wiesel was. The letters they sent are perhaps less flowery than some the Nobel Committee has received in the past:

U.S. Senate

January 28, 1984

Members of the Committee:

It is my honor to propose Mr. Elie Wiesel for the 1984 Nobel Prize for Peace. As you well know, Mr Wiesel has dedicated most of his life toward the goal of peace throughout the world. In my opinion, you could not go wrong by awarding the Nobel Peace Prize to this most deserving gentleman.

With Respect

Barry Goldwater

By Strochlitz’s count, more than 50 senators and 140 representatives have written to Oslo on Wiesel’s behalf. More than 70 members of the West German Bundestag have also nominated Wiesel. After getting a few dozen senators under his belt, Strochlitz began grouping them in interesting ways. One year he got the entire Massachusetts congressional delegation to nominate Wiesel. Another year he solicited letters from all the members of the Senate Banking Committee.

Boston University’s John Silber helps out

Strochlitz was helped by John Silber (right), the president of Boston University, where Wiesel teaches. Silber called Strochlitz “the real strategist and campaigner.” “Strochlitz did everything in his power,” Silber said. “he would say to me: ‘John, you know these people in Congress.’ I’d write to them and send copies of their responses to Strochlitz, so he could keep track of everything we were doing.” Silber said that he is especially delighted at Wiesel finally winning the prize, since it is the second such award bestowed upon someone associated with his school. Martin Luther King, who won the Peace Prize in 1964, was a student at Boston University during the 1950’s.

Strochlitz was helped by John Silber (right), the president of Boston University, where Wiesel teaches. Silber called Strochlitz “the real strategist and campaigner.” “Strochlitz did everything in his power,” Silber said. “he would say to me: ‘John, you know these people in Congress.’ I’d write to them and send copies of their responses to Strochlitz, so he could keep track of everything we were doing.” Silber said that he is especially delighted at Wiesel finally winning the prize, since it is the second such award bestowed upon someone associated with his school. Martin Luther King, who won the Peace Prize in 1964, was a student at Boston University during the 1950’s.

In Silber’s letters to the Nobel Committee, he argued that Wiesel was not just a spokesman for survivors of the Holocaust, but a voice for victims everywhere. Each year that he re-nominated Wiesel, he wrote the committee about some new effort of Wiesel’s on behalf of the oppressed–whether his work for Cambodian boat people, or Soviet Jews, or Arab refugees, or those disappeared in Argentina. A typical letter from Silber to the committee points out that “Wiesel traveled at considerable risk to his personal health and safety into the jungles of Honduras, where he met with the Miskito Indians.” Attached was an op-ed piece Wiesel published in the Los Angeles times, detailing the Miskito’s plight. As Silber put it one year, “I am sure that my letter will not be the first, nor indeed the only such letter to reach you…”

Another of Silber’s tactics has been to suggest appropriate anniversaries for the Nobel Committee to make use of in honoring his friend. In 1984 he wrote of the connections between Wiesel and Orwell. The following year Silber’s letter reminded the committee that it was the 40th anniversary of the liberation of the death camps. Wiesel’s friends searched endlessly for a new “peg” on which to hang the same old story.

Silber said Wiesel never inquired about the effort to get him the prize, though he was aware of it. “He never asked anybody, never asked me, never asked Strochlitz,” Silber said. “We said, ‘stand still, Elie. Step aside, do your work. Don’t worry about our work, which is to make them [the Nobel Committee] aware of yours.'” Silber added, “Nobody wins unless the Nobel Committee knows about them.” Silber and Strochlitz both vociferously decline any share of the credit for Wiesel’s prize in 1986. “That would be like the trainer claiming he’s the race horse,” Silber said. “We may have fed the oats, and curried the flanks. But that horse could run.”

Wiesel gained by being a “non-controversial” selection

According to all published reports, Wiesel has been on the Nobel Committee’s short list for the past few years. And this year members of the jury thought it necessary to make a non-controversial selection. Last year’s prize, which was shared by Soviet doctor Yevgeny I. Chazov, of the Boston-based Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear war, humiliated the committee when it was revealed that Chazov had denounced laureate Andrei Sakharov several years earlier. In 1986 it was the West’s turn to be mollified.

Looking down the list of past winners, one wonders what the prize is actually for. Some years it appears to reward good deeds on a large scale. Other times, it seems to honor political leadership. On a few occasions, such as 1973, when it was awarded jointly to Henry Kissinger (left ) and Le Duc Tho, it has seemed closer to a war prize than a peace prize. These days, it’s a rather amorphous accolade–sort of a moral hall of fame for the indisputably decent.

Looking down the list of past winners, one wonders what the prize is actually for. Some years it appears to reward good deeds on a large scale. Other times, it seems to honor political leadership. On a few occasions, such as 1973, when it was awarded jointly to Henry Kissinger (left ) and Le Duc Tho, it has seemed closer to a war prize than a peace prize. These days, it’s a rather amorphous accolade–sort of a moral hall of fame for the indisputably decent.

Whatever the Nobel Peace Prize signified, it’s clear that people lobby for it. Nobody seems quite sure what Japanese prime minister Eisaku Sato won his Nobel for in 1974, but it’s well known that he hired a public relations firm to help his campaign along. Jimmy Carter, Armand Hammer, and Indira Gandhi have been among the more recent campaigners who appear to have failed in drives for the prize. (Hammer reportedly once sent Ann Landers a jade necklace with a note asking if she could help him get nominated for the prize.) Mohandas Gandhi never campaigned for, and never got, the most coveted prize on planet earth.

Because the prize has such prestige, it’s a bit disquieting to discover that the winners actually wanted it. Nobody wants to think that the Mother Theresa’s of the world bid for earthly reward. In fact, Mother Theresa never did campaign for the Nobel Peace Prize. But she seems to be the exception, Elie Wiesel the rule. ~

____________________________________________________________

This is the photograph (in background) in which the New York Times identified Elie Wiesel, as a 16 year-old boy, for the first time in Oct. 1983 when the campaign for a Nobel Prize for Wiesel had gotten underway. In 1986, just days after winning the coveted prize following his three-year campaign, he stands in front of the photo during his visit on December 18, 1986 to the Holocaust Memorial Center ‘Yad Vashem’ in Jerusalem.

How true to life is Wiesel’s description of Buchenwald in Night?

Written on July 18, 2011 at 12:59 pm, by Carolyn

By Carolyn Yeager

Ken Waltzer wrote in his comment on this blog on June 27th:

“More important, Elie Wiesel’s commentary in Night bears fairly close resemblance to the actual experiences he had at Buchenwald—as recorded in camp documents.” (my italics)

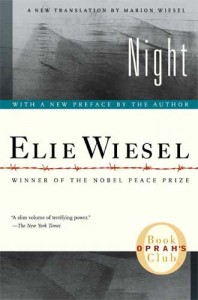

What are we to make of the words “fairly close resemblance?” According to Waltzer—and to Wiesel—Wiesel is writing down his own experience. “Every word is true!” Wiesel has said of his book Night. Thus it should exactly resemble the actual experience he had. I’m going to examine closely what is written in Night about Buchenwald to see if that is the case.

It’s not too difficult because the newest English edition of Night1—a new translation by wife Marion Wiesel which changes (corrects) some of the more blatant “boo-boos” found in the original 1960 edition—comprises only 115 pages. Of that, Wiesel’s description of his time at Buchenwald begins on page 104, giving it only 11 pages (one page being blank).

Wiesel wrote a new preface for this new translation in which he tries to answer some of the more common criticisms of his book. His answer to the differences between the Yiddish And the World Remained Silent and Night is that he cut passages he thought might be superfluous … or “too personal, too private, perhaps.” Strange thing to say since he had already published it. Concerning Buchenwald, he quotes the original writing about the death of his father, where the club-wielder is called “an SS” three times! In Night, as you will see below, this person becomes simply “an officer.” Naturally I ask: Did this scene even happen? Wiesel also tries to explain why he cut out from the ending so much of what was in the Yiddish version, but in doing so he leaves unmentioned an extensive part of what he cut. I have quoted these two endings in Shadowy Origins of Night, Part II.

Wiesel begins his experience at Buchenwald by writing that upon reaching the entrance to the Buchenwald camp along with his father and all the new arrivals from his transport, the SS counted them and they were directed to the Appelplatz (roll call area inside the camp) where loudspeakers ordered “Form ranks of fives! Groups of one hundred! Five steps forward!” He then writes, “A veteran of Buchenwald (as he puts it), told us that we would be taking a shower and afterward be sent to different blocks.” He makes it sound as if it were one of those among them, but it actually had to be a Kapo.

He writes that hundreds of prisoners crowded the shower area and made it difficult to get in, therefore his father wanted to find a place to sit down and wait—which he did in a pile of snow where there were other ‘bodies’ sticking out. Dead or alive we’re not told. It’s one of those literary scenes wherein Eliezer confronts Death via his fear of his father’s death. He writes: “This discussion (with his father) continued for some time.” Then … “sirens began to wail … lights went out … guards chased us toward the blocks.” They obviously did not get a hot shower. Wiesel adds: “The cauldrons at the entrance found no takers.” 2

Are we to believe that the kapos, or “veterans of Buchenwald,” allowed non-disinfected, non-showered new arrivals into the barracks, possibly carrying lice and other vermin with them? No way could this have happened. Yet Wiesel writes: “We let ourselves sink into the floor. To sleep was all that mattered.” I guess it was okay because they didn’t get into the beds.

In the morning, having lost track of his father the night before, he went to search for him. What about the regimentation? What about the early morning roll call? Wiesel writes: “I walked for hours without finding him. Then I came to a block where they were distributing black ‘coffee.’ ” 3 He heard his father’s voice asking for some coffee. He brought it to him. “He was lying on the boards,” meaning, I suppose, a bare bunk. Then, “We had been ordered to go outside to allow for cleaning of the blocks (barracks). Only the sick could remain inside. (If that was the case, they were not fumigating.) We stayed outside for five hours. We were given soup. When they allowed us to return to the blocks, I rushed toward my father” … who told Eliezer he had not been given any soup because “they said we would die soon and it would be a waste of food.”

Apparently, he stayed with his father in that barracks, making sure he was fed. Were they allowed to live in whatever barracks they chose? Again, there is no explanation given for this. He then writes that on the third day after their arrival everybody had to go to the showers, even the sick. Having done that (with no description of the process at all), they again had to wait “a long time” outside the barracks while they were being cleaned.

He fills a couple of pages with scenes of watching his father deteriorate amidst all the heartlessness. Then, after a week, a Blockälteste (block warden) told him he couldn’t save his father and he should help himself by eating his father’s rations. Instead, he pretends to be sick so he can stay in the barracks with his father. He doesn’t go to roll call. Now comes the famous passage in which he writes: “In front of the block, the SS were giving orders. An officer passed between the bunks. My father was pleading: “My son, water…I’m burning up…My insides …” The officer shouts at him to be quiet, walks over with a club and hits him “a violent blow to the head.” On that night, January 28, 1945, his father allegedly died.

The main problems with reality in this passage are:

1) The SS is known to have not been active inside the camp; the prisoner-trustees, usually communists, took care of giving the prisoners their orders. So the SS would not be in front of the block giving orders.

2) “An officer” can only be an SS officer. But they never came inside the barracks. Inmates, no matter how much “in charge” they might be, were not called officers. So who was this mysterious “officer” who was inside the barracks? Not SS at all; just part of the fiction and another attempt to assign brutalities to the SS.

Eliezer says he did not weep for his father. He was numb. He was transferred to the children’s block, where he remained with 600 others until April 11. That’s two and a half months, yet he tells us nothing of that time except that he did have an appetite and his only interest was getting an extra ration of soup. On April 5 (he knew the exact date) “we were inside the block, waiting for an SS to come and count us. He was late. Such lateness was unprecedented in the history of Buchenwald.”

Same problem as above: the official story (and Waltzer’s story) tells us that the communist “veterans” had these boys hidden away in the “small camp” where they cared for them, keeping them away from the SS and the camp authorities. We know that the SS did not go inside the blocks. Yet Wiesel writes that they did every day because on this day they were late. Covering for Wiesel, Waltzer writes on his website:

…the 16-year old Wiesel was assigned to a special barracks that was created and maintained by the clandestine underground resistance in the camp as part of a strategy of saving youths. This block, Block 66, was located in the deepest part of the disease-infested little camp, a separate space below the main camp at Buchenwald that was beyond the normal Nazi SS gaze (the local SS officer actively cooperated and conducted appels inside the barracks).

The barracks was overseen by block elder Antonin Kalina, a Czech Communist from Prague, and his deputy, Gustav Schiller, a Polish-Jewish Communist originally from Lvov. Odon Gati, a Communist from Budapest, was stubendienst. Schiller, who appears briefly in “Night,” was a father figure and mentor, especially for the Polish-Jewish boys and many of the Czech-Jewish boys, but he was less liked, and even feared, by Hungarian- and Romanian-Jewish boys, especially religious boys, including Wiesel. He appears in “Night” as a menacing figure, armed with a truncheon.

First, Waltzer mentions the underground. But they did not have the power to hide away the youths who were assigned to the special barracks 66. It was a policy of the Camp Commandant to separate these children to keep them safe, to feed them as well as possible, and they were fully aware of the children’s barrack 66 where they were kept. Thus. there may have been a “local SS officer” assigned to look after Block 66 to make sure everything was being done according to regulations … that is, even to supervise, to some extent, the communist block leaders. The story that it was the communists who “saved these boys from death” is a fiction that was created later, after the liberation of the camp and the formation of the Buchenwald association which was made up of former prisoners of communist persuasion. It was the camp authorities who made the decision to place the “children” away and apart from the adult prisoners, not the underground resistance.

Second, Wiesel writes in Night, “Gustav, the Blockälteste, made it clear with his club” that they had to obey the order to gather in the Appelplatz. Doesn’t this imply that the communist overseers were not necessarily acting as “father-figures” and mentors, but simply as guards? Also note that the kapo Gustav was carrying a club and used it, while earlier it was an “officer” in the barracks who wielded a club against Eliezer’s father. Relative to this, Ferenc Kornfeld reports : “Without exception, the Kapos all had big sticks.” He also said a Kapo armband went with a double food ration. And, “They continually shouted and they hit people on the head and the neck.” Kornfeld wrote about Buchenwald: “There were common criminals, murderers and thieves, in concentration camps too. They were called the “Blockältesters”. They were the “Kapos” (bosses). As they were murderers, they had black triangles on their uniforms. The Kapos hit and slapped all of us.” So much for the idea of Blockälteste’s as mentors.

The abrupt ending of Night

Wiesel claims on pages 114-15 (the last two pages of the book) that on April 5 everyone, even the children, were ordered to gather in the Appelplatz. On the way, some prisoners told them to go back because the Germans planned to shoot them. They turned around and on the way back they learned that “the underground resistance of the camp had made the decision not to abandon the Jews and to prevent their liquidation.” What kind of nonsense is this? Well, it is “the story” which evolved that these communists at Buchenwald finally, on the very last day, fought the Germans. What really happened was the Germans were ready to abandon the camp on the 11th, which they did. Wiesel simply picks up that official fiction of the underground resistance and incorporates it into his narrative. I don’t think the Germans ever intended to evacuate the children and youths.

Apparently, after the 5th, blocks of prisoners were being evacuated to other camps. By April 10, Wiesel writes, “we had not eaten for nearly six days except for a few stalks of grass and some potato peels found on the grounds of the kitchen.” From whom did these potato peels come? Did their communist keepers gather them and bring them to the youths inside the barracks? Did the boys roam around freely and eat grass? At ten o’clock the next morning, he tells us, the SS positioned themselves around the camp and began to herd the remaining inmates toward the Appelplatz. At this point the underground resistance members appeared “from everywhere” with guns and grenades. Eliezer and the other children “remained flat on the floor of the block.” (Therefore they saw nothing.) By noon, the SS had fled and the resistance was in charge. The first American tank arrived at 6 p.m.

Wiesel now wastes no time in concluding the book. He says he became very ill from food poisoning three days later because they “threw themselves on the provisions.” He spent two weeks in the hospital “between life and death.” One day he got up and looked in a mirror and saw only a corpse gazing back at him. This was at the end of April or first of May 1945. Yet he recovered so well that we see a healthy, smiling boy in the picture supposedly taken of him at Ambloy in late 1945 … or is it early or mid 1946?

It’s interesting that Wiesel made such a point later on of maintaining he had vowed in 1945 to wait ten years to write down his experiences. The reasons given, including that his memory would be sharper after ten years, are completely bogus—especially since his book bears little resemblance to the actual camps as we know them to be. The much longer Yiddish version was published in 1955-56. The abridged French version La Nuit in 1958; the English Night in 1960.

Conclusions

I have to say Wiesel doesn’t describe Buchenwald at all. You don’t know anything about Buchenwald from reading Night. You don’t learn much about Eliezer or anyone else. You are given an impression of suffering, without rhyme or reason, so Buchenwald becomes synonymous with suffering, that’s about it. We don’t know what it looks like. We don’t know the name or the physical appearance of any person, not even Gustav carrying a club, who is said elsewhere to have had red hair. Wiesel makes up a story about “an officer” using a club in the barracks when it could only be a kapo (if it was anyone at all). He doesn’t tell us anything about the children in the barracks where he stayed for 2 ½ months. He doesn’t describe the few days after liberation, before he got sick. One did not have to be at Buchenwald to write what he wrote!

Ken Waltzer also writes at his website:

Elie Wiesel has acknowledged the role played by the clandestine underground and political prisoners in saving children and youth at Buchenwald, especially in his autobiography, but he did not attend to this in “Night.” It was not his purpose or focus in that book. Many of his fellow barracks members, however, who are still alive and remember very well their days and nights in Block 66; their relations with Kalina, Schiller and others; and the hope provided to them there, have been helping fill in the story.

You can see a couple of these fellow barracks members here: Scroll down for Excerpts from the “Boys of Buchenwald” discussion panel (7.45 minutes) You can judge for yourself how impressive they are…or not. Neither one mentions Elie Wiesel.

Endnotes:

1. Elie Wiesel, Night, Hill and Wang, New York, 2006, 120 pgs.

2. This can refer to soup or disinfectant being available at the entrance to the barracks. Obviously, Eliezer and his father dawdling by having their long conversation caused them to miss out on both shower and whatever was in the cauldrons. Just another example of the intended vague descriptions permeating this book.

3. In the book, “coffee” is in quotes signifying it wasn’t real coffee. I left off the quote marks in the original writing because of the quote mark signifying the end of the sentence. Poor judgement on my part, but whether it was real coffee or not wasn’t the focus of my attention in this critique. However, the sharp attention of the author of the Scrapbookpages Blog picked up on this and wrote about Wiesel’s failure to know that real coffee was not served in the camps. My apology to “Furtherglory” for misleading him and to my readers also. I have added the quote marks since reading the blog at Scrapbookpages Blog.

New Photo of Elie Wiesel in France?

Written on July 12, 2011 at 8:31 pm, by Carolyn

By Carolyn Yeager

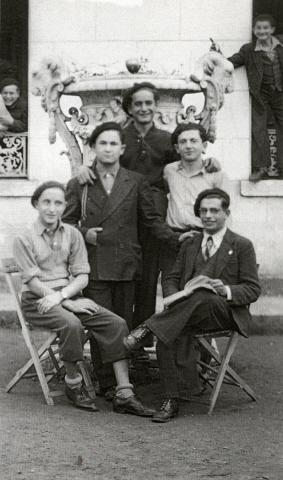

Pictured: front left, Kalman Kalikstein; Binem Wrzonski (middle right), and Elie Wiesel (back center).

This picture is now available for purchase at the USHMM website. The information about it is given as follows:

Date: 1945-1946

Locale: Ambloy (Loir-et-Cher) France

Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Binem Wrzonski

Copyright: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Title: Group portrait of boys in the Ambloy children’s home.

USHMM Commentary: In June 5, 1945, Binem joined a group of boys and young teenagers, known as “The Buchenwald Boys” who were brought to France in a special convey under the sponsorship of the O.S.E. They first were brought to Ecouis in Normandy. An aid worked (sic) helped Binem to make contact with his one surviving sibling, Towa who had spent the war in the Soviet Union. From Ecouis the children were taken to either secular or religious homes. Binem at first wanted to go to a secular home, but Leo Margolis, a German Jew who was in Buchenwald for approximately six years and helped care for the children, persuaded him to go to a religious home. Binem then went to Chateau d’Ambloy. From there he went to Taverny. Then together with two other teenagers, with Elie Wiesel and Kalman Kaliksztajn, he accompanied a group of younger boys to Chez Nous in Versailles where worked as a counselor. From this experience, Binem decided to become a teacher. After training in France, he immigrated to Israel and became the principal of a Youth Aliyah boarding school. In Israel he met and married Rahel Schlezinger and they went on to have five children and many grandchildren and great-grandchildren. In 1983 Binem returned to Lodz and erected a new marker at his father’s graves including the names of all of his family members who died during the Holocaust. [end of USHMM commentary]

* * * *

Binem came from Buchenwald, but not Elie Wiesel and maybe not his good friend Kalman!

What is amazing about this commentary on the picture above is that Elie Wiesel is NOT said to have been at Buchenwald with Binem, but encountered him at Taverny. Elie and Kalman, according to Binem, accompanied a group of younger boys to Chez Nous in Versailles where they worked as counselors. This actually makes a lot more sense. A narrative in which Elie Wiesel is not a withdrawn, scarred youth from the concentration camps, but possibly arrived in France sometime during the war—helped by the Jewish network and placed in the children’s welfare institutions—is quite possible. There, he associated with some of the youths who were sent after the war, and developed his “knowledge” of concentration camp life from them.

Is this why he had no interest in gaining French citizenship—because he was devoted to the Jewish cause of Eretz Israel and always connected to and working with the Jewish Underground? (See Elie Wiesel and the Mossad)

Was Elie Wiesel actually a youth counselor for Buchenwald boys, rather than one of them?

Can this explain why he remained with the welfare agencies for so long and was one of the oldest to leave his last home at Versailles to live on his own? His friend Kalman left for Israel in 1947 before Elie managed to get a room of his own “at the end of summer” at the age of 19. This would have been after his birthday on Sept. 30.

Compare this photograph with the one below, which the USHMM identifies as:

Group portrait of the staff and boys of Ambloy, an OSE home for religious youth.

Among those pictured are (First row, left to right): Natan Szwarc, Izio Rosenman, Deblin, unknown and perhaps Berek Rybsztajn. (Third row): Abraham Tuszynsky (2nd from left, first boy next to woman), Andre Zelig is in the center with a tie and his hands on the boy in front of him and Elie Wiesel (second right of Tuszynsky). Binem Wrzonski is to the right of Elie Wiesel. The donor, Jakob Rybsztajn is in the fourth row, fifth from the left.

This picture is available for purchase from USHMM website. The information given about it is as follows:

Date: 1945

Locale: Ambloy, (Loir-et-Cher) France

Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Jacques Ribons

Copyright: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

The inscription on the back reads “Before our departure from Chateau Ambloy for Paris.”

USHMM Commentary: Jakob Rybsztajn (now Jacques Ribons) is the son of Peretz Rybsztajn (b. 1905) and Bella (Bajal, b. 1906) Rybsztajn. He was born on August 15, 1927 in Strzemieszyce Poland where his father was a textile manufacturer. He had two younger siblings: Bernard (Berek) who was born in 1929 and Esther who was born in 1935. In 1933 the family moved to Zelow, Bella’s home town. The family remained there until 1936 when it moved back to Strzemieszyce. In 1939 Germany invaded Poland later the Rybsztajns were forced to move to a ghetto. Jakob attended a ghetto Hebrew school. Peretz Rybsztajn, his father, worked with or was close with the Jewish Council but he soon disappeared. After the ghetto was liquidated, probably in June 1943, Jakob and Berek, who initially had hid, were forced to return and then sent briefly to Bedzin. In September they were deported to the Blechhammer concentration camp where they were forced to work unloading cement from train cars, insulating oil and fuel tanks with asbestos, and cementing steel forms to the tanks. They lived in a barrack with other boys their ages, including Kalman and Heniek Kaliksztajn, two brothers also from Strzemieszyce. In January 1945 the Germans liquidated the camp in advance of the Soviet army, and the brothers were sent on a death march via Gross Rosen and by open train to Buchenwald. They arrived in Buchenwald on February 10, 1945, and were placed in the children’s block, Block 66.

Jakob and Berek remained together in block 66 until they were liberated in Buchenwald by the U.S. Third Army in April. The boys in the barrack, under the supervision of Gustav Schiller, the deputy block elder, did not work and received occasional Red Cross packages distributed from other prisoners in the camp. After liberation, the Rybsztajn brothers joined a children’s transport to Ecouis in France, sponsored by the O.S.E., where they were through the summer. But, as they were religious, they were sent from there with other religious boys, including the Kaliksztajn brothers, also Elie Wiesel, to children’s homes in Ambloy and Taverny. Then Jacques came to Paterson New Jersey and later enlisted in US army during the Korean conflict. He arrived in New York in February 1947 on board the Gripsholn, a Swedish ship. Berek was adopted by the Homberger family in California. Later he was in Israel and served in the Israeli Defense Forces; he returned to California in the late 1950s. Jacques also settled in Los Angeles. The Rybsztajn parents, Perez and Bella Rybsztajn, and their sister younger sister Esther perished in Auschwitz, it is believed, during 1943. [end of USHMM commentary]

* * * *

If it can be proven that this is indeed Elie Wiesel in the two pictures, we still do not know if he arrived in Ambloy from Buchenwald.

We have learned that others were there already and the Buchenwald boys joined them. He may have been one of those who were already there. The commentary states as an afterthought that “also Elie Wiesel” was among those sent to Ambloy and Taverny. Where are the records that must have existed? In what capacity was Elie Wiesel there?

The person identified in each photo above as Elie Wiesel is dressed in the same clothing, so the pictures were most likely taken on the same day. The boy Binem may simply have taken off his jacket in the more casual top picture. But where is Kalman in the large group photo? He is not identified and appears to be missing. Rather than pictures on more than one occasion, we have two different pictures taken at the same time.

The group is dressed for travel to Paris (Versailles). It must have been later than 1945 that they transferred to the home in Versailles, so this picture should probably be dated 1946, as is the top picture. All of these questions I raise show the poor scholarship done by the USHMM and the holocaust historians in general. Slip-shod reporting is picked up from here and there, thrown together, becoming the “story” that fits the bill. Thus we have Elie Wiesel’s name stuck in where they want it to be, to try to show that he was one of the Buchenwald boys, when actual proof doesn’t exist.

These photographs only portray someone who could be Elie Wiesel at a home in Ambloy, France where some of the boys from Buchenwald, and also Jewish boys from elsewhere, lived for a time.

As far as the next picture is concerned, I now cannot be sure that these boys are arriving from Buchenwald. They are only identified as Jewish DP (displaced persons) youth at the USHMM website:

Group portrait of Jewish DP youth at the OSE (Oeuvre de Secours aux Enfants) home for Orthodox Jewish children in Ambloy. Elie Wiesel is among those pictured. [Photograph #28147]

This photo is also available for purchase at USHMM website. The information given about it is as follows:

Date: 1945

Locale: Ambloy, (Loir-et-Cher) France

Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Robert Waisman. Willy Fogel

Copyright: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

In this case, none of the boys are identified by name. In the long commentary that accompanies the picture on the page, there is no mention at all of Elie Wiesel. I will say that no one in this picture is wearing a beret! Once again, if the USHMM or Prof. Ken Waltzer claim that Elie Wiesel is in this picture, they must point him out.

It has never been disputed that Elie Wiesel was in France. But just when he arrived and what he was doing there is not documented.

* * * *

The next step for the reader is to compare the face of “Elie Wiesel” in the first two photos above with the faces of “Elie Wiesel” in the famous Buchenwald photo and the boys marching out of the Buchenwald gate, plus his portrait as a 15-year-old, that are found at “The Many Faces of Elie Wiesel.” They can’t all be Elie Wiesel. It’s up to you—and up to USHMM and Ken Waltzer, and how about the old liar Elie Wiesel himself!—to decide and announce which ones are. When that is clear, we can then decide what the pictures are telling us.