Where is Elie's Tattoo?

Elie Wiesel has told us for over 50 years that he was tattooed at Auschwitz in 1944, and that his tattoo number is A7713. He has repeatedly said that he still has this original tattoo on his arm. Just last March in Dayton, Ohio, Elie met with the press, high school and college students, and 2300 members of the local community. As reported in the Dayton Daily News , one student asked Wiesel if he still has his concentration camp number and if it serves as a reminder of those terrible experiences. "I don’t need that to remember, I think about my past every day," he responded. "But I still have it on my arm – A7713. At that time, we were numbers. No names, no identity."

Featured Post

Posted on October 2, 2021 at 6:36 pm

“Elie Wiesel Cons the World” makes our final call on Elie’s tattoo

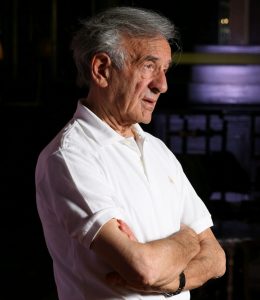

Close-up of Wiesel’s arms from the photograph taken in 2006 by Eyal Toueg, published after Elie Wiesel’s death.

By Carolyn Yeager

It’s been five years now since Elie Wiesel died and his body was buried in a plain pine coffin.

This website premiered in July 2010 with the question: “Where’s the tattoo?” No one had ever seen it, yet Wiesel claimed to have it as proof he was an inmate at Auschwitz in 1944. Please refer to “Where is Elie’s tattoo?” before you read further.

In seven years, this site had learned and published a great deal [over 130 articles] about Elie Wiesel’s life events and the incredible trail of lies he left in his wake. But we had still not seen the tattoo! That is, until the above photo was published by Haaretz, a leading Israeli newspaper, a week after his death. Behold! the distinctive appearance of a bluish smudge on ElieWiesel’s bare left forearm. The photo, said to be taken in Israel in 2006 by Eyal Toueg, is high-resolution and gives every appearance of being an authentic representation of Wiesel at that time—in other words, not photo-shopped. Haaretz is a generally reliable source with a reputation to protect. Since then, I’ve seen no further mention of the photograph.

My takeaway on what we see there is that it is clearly NOT the number A-7713, which is what Wiesel claimed all his adult life he had. He lied—and got away with it. Please see my articles “How Wiesel’s ‘tattoo’ looks from where I’m sitting” and “New (old) pictures come to light in wake of Elie Wiesel’s death” for my impressions in 2016.

Five years later I can say with confidence that whatever it was that may have been on his arm and appears to have possibly been removed was never the number A-7713. (Why? Because it it were A-7713, it would not have been removed while he was still claiming it was there.)

“Appears to have been” is the key here because we’re dealing solely with appearances. We have no statements from Wiesel’s intimates and allies about the tattoo. When it comes to questions about that, they are mute. We also have other images of Wiesel’s bare arm with nothing appearing there or with what could be a faint trace of a number (see below). However, no matter how much these “faint traces” are enlarged, no number can be made out—it is seen to be only a ‘shadow’ on the arm.

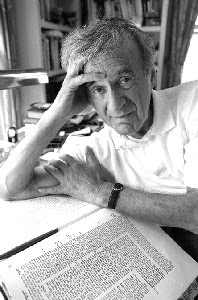

This photo taken on the same day as the one above in 2006. Wiesel is wearing the same shirt and his wristwatch is facing down. But the faint mark on his arm doesn’t match the image above.

The explanation for these last two photos, one taken in 1945 and the other on the same day in 2006 he was wearing the white knit shirt, is that they were both uploaded to the Internet by Loupi Smith and no one else! Neither of these images are found in the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum collection, the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum, or even at Yad Vashem. If they were proof that Elie had a tattoo, wouldn’t they be there?

Loupi Smith is a notorious French Jew who’s long been engaged in battle with revisionists (known as negationists in France), most especially with the honorable Vincent Reynouard. It’s most likely that Smith took images of Wiesel without any mark on the arm and applied the desired effect directly to the photographic print he had obtained. He then uploaded these to the Internet and waited for them to be found, or had friends/agents who “found” them.

As to why Haaretz decided to publish this photo right after Wiesel’s death, Haaretz will have to answer that. We are not mind-readers and have to depend largely on honesty from the parties involved, but honesty has never been forthcoming from Holocaust advocates. For example, see my articles about AP reporter Verena Dobnik who in Nov. 2012 wrote that Wiesel showed her his Auschwitz tattoo by “pulling back his left jacket sleeve” during an interview she was conducting with him. Of course, she didn’t and never would say what it was, just that it was an “Auschwitz tattoo.” See “AP reporter doesn’t reply to questions about seeing tattoo on Elie Wiesel’s arm” and “AP stonewalling legitimate questions about reporter seeing Elie Wiesel’s tattoo.” Nothing unusual here, though—it’s the usual behavior from all media and government sources when it comes to anything “holocaust.”

FINAL CONCLUSION: Elie Wiesel lied about his tattoo. All the feeble explanations/excuses put forward by his supporters and fans for why he refused to show it are inadequate in the face of the proofs we’ve assembled. Wiesel stole the identity of Lazar Wiesel, who was 13 years his senior and who was recorded as being an inmate at Auschwitz-Birkenau (tattooed with A-7713) and at Buchenwald camps in 1944-45. No records for a 16 or 17 year old Eliezer Wiesel born in 1928 exist at either camp.

If he lied about the tattoo, it is certainly believable he lied about being in Auschwitz and Buchenwald. In support of that possibility are the facts that his stories and descriptions don’t match the well-known reality of the camps; his timelines are off; people who were known to be there at the same time he was, even housed in the same buildings, never mentioned seeing him—either before or after he became famous. All this and more is documented at this site.

Elie Wiesel’s “Idea”

Equally important to Elie’s lack of the claimed tattoo is, in my opinion, his admitted twisting of what it means to be a witness. There are two parts to his approach: 1) What happened may not be “true” and what is the “truth” may not have actually happened, and 2) Every Jew should be a witness to the Holocaust regardless of whether they actually participated. Part 2 is made possible by part 1.

Wiesel announced his willingness to deceive in several of his books, and in interviews. Even though he told us exactly what he was doing, it seems no one wanted to take it seriously. The sainthood of Elie Wiesel was too appealing.

Of his several statements, covered in my article “Elie admits his true stories never happened,” I think the most compelling was in a 1970 interview with Gilles Laponge, published in the book Elie Wiesel: Conversations (2002). You can find the interview online HERE at Google Books. Wiesel said:

Of his several statements, covered in my article “Elie admits his true stories never happened,” I think the most compelling was in a 1970 interview with Gilles Laponge, published in the book Elie Wiesel: Conversations (2002). You can find the interview online HERE at Google Books. Wiesel said:

In [my] book “One Generation After” there is a sentence which perhaps explains my idea: “Certain events happen, but they are not true. Others, on the other hand, are, but they never happen.” So! I undergo certain events and, starting from my experience, I describe incidents which may or may not have happened, but which are true. I do believe that it is very important that there be witnesses always and everywhere.

[…]

The people of my generation are, in various ways, all survivors. We must prevent the Holocaust from being erased from the memory of the world.

He’s telling us he’s writing fiction “based on his experience” but insisting it’s ‘true’, and even 100% true. What is the basis of his experience? Being a Jew. A Zionist Jew. Wiesel’s life history of being a Hasidic Jew is primary in his experience, according to his own words. This means he accepts the following and has said so:

- Belief taking precedence over Reality;

- Religion over History;

- Storytelling over fact-finding;

- Hearsay over first-person evidence; and

- Feelings over Justice.

In other words, it’s Ashkenazi Jewish mysticism vs European Christian Law. It’s interesting to note that at Boston University, where Wiesel had a cushy “professorship” for many years, he taught in the Religion and Philosophy Departments, not the History Department. See my article on BU here.

A little further in the interview Wiesel continues with the cloudy language:

“I believe in a way we are all culpable even though the guilt of the torturer is not that of the witness or the survivor. Do not see in my words the least resignation to evil. […] No, evil is absurd the same way the Holocaust is absurd. I remain convinced that this event, the most significant in history, might very well not have happened.”

Everyone can be a survivor, with the important job of preventing the memory of the Holocaust from being lost or “erased.” For this purpose, apparently everything and anything goes. Making things up to be far worse than they actually were is nothing unusual. It’s considered necessary to reinforce the memory.

When Wiesel claims that “every word” in Night “is true,” he’s using a definition of “truth” different from the standard dictionary meaning. When testifying in a court of law, the lawyers and judges should first establish what is his understanding of truth, but they never have.

On this basis, Wiesel received award after award from prestigious Gentile groups, all the way up to the Nobel Peace Prize. Wiesel has indeed conned the world.

We pronounce Elie Wiesel a false witness from beginning to end.